The Australian influenza season 2023. Coming to a patient near you?

After a lull in influenza virus infection numbers during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2023 could see a return to pre-pandemic influenza epidemic patterns. With the young and older people most at risk of severe infection and associated adverse events, a suite of influenza vaccines is available to suit these vulnerable age groups.

Now that we have entered autumn, the annual influenza epidemic is not far away. Influenza case numbers usually begin to rise in April to May, progressing to a full epidemic during the months of June, July and August, often extending into September before waning in October. However, the timing and severity of influenza seasons is variable and unpredictable, so now is the time to get prepared for the season. This article summarises the trends in influenza epidemics in Australia during the years of the COVID-19 pandemic and outlines measures to reduce the burden of influenza on the individual and the community as a whole. Vaccination is still our best defence against influenza and is suitable for all age groups, except for those under 6 months of age. GPs play a key role in the annual influenza vaccine rollout and in encouraging patients to be vaccinated with the most suitable vaccine before the season begins.

Learnings from the past few years

What has been learned from the most recent influenza seasons here in Australia? The adage often repeated by those who work in the influenza field, ‘If you have seen one influenza season, then you have just seen one influenza season’, reflects that previous influenza seasons do not necessarily predict the incoming influenza season. This is what is both intriguing and frustrating about influenza and the reason why is it difficult to predict the severity of seasonal influenza each year.

The COVID-19 pandemic over the last three years has provided some insights into the main drivers of influenza epidemics in Australia. The strict nonpharmaceutical measures taken to mitigate COVID-19, including lockdowns, quarantining, mask wearing and international (the main contributor) and domestic border closures, had the somewhat unexpected effect of almost eliminating influenza circulation in Australia during both 2020 and 2021. Although these measures stopped influenza in its tracks, it didn’t stop all respiratory infections from widely circulating. High case numbers of respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, parainfluenza, rhinovirus and human metapneumovirus persisted and continued to circulate in most states during these pandemic years; however, for some, their recent seasonality pattern was different from their pre-pandemic years.1

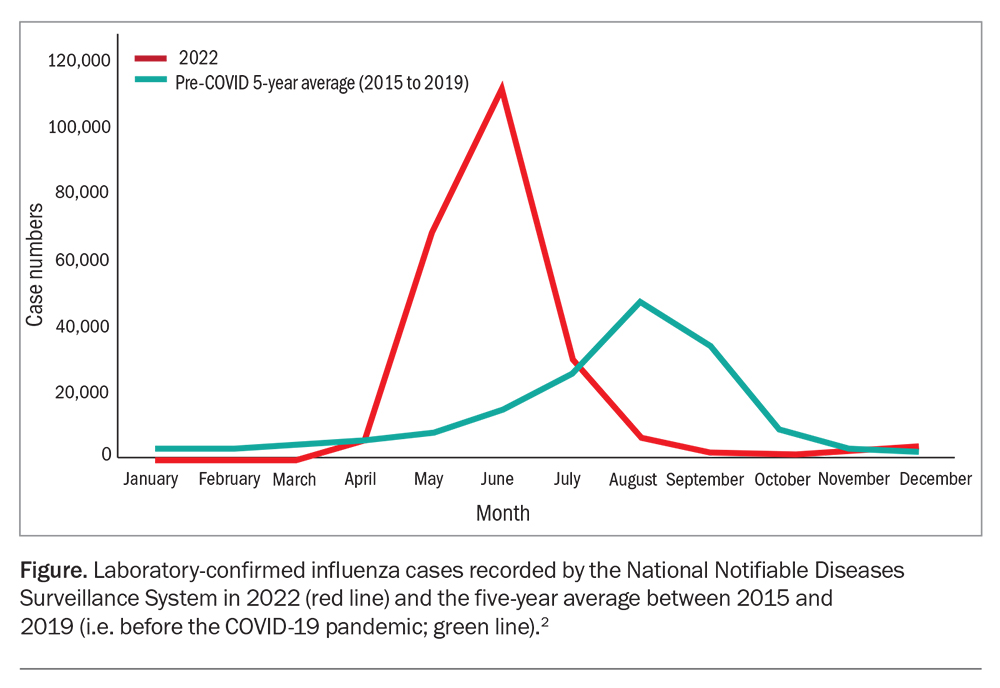

Australia’s international borders reopened on 21 February 2022 (Western Australia delayed re-opening until 3 March 2022) to returning Australian residents and tourists, provided they were fully vaccinated against COVID-19. This timing coincided with the end of the northern hemisphere winter of 2021-22, a period that also saw the return of influenza into most of these countries. After COVID-19 restrictions were relaxed, laboratory-confirmed influenza cases recorded by the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) quickly rose in Australia, from a mere 39 cases in February 2022 and peaking in June (Figure 1).2 Case numbers fell rapidly in July and by the end of August, the month in which influenza cases are usually at their peak (pre-COVID-19), the epidemic had subsided.

Overall, 2022 had a moderately severe influenza season, with a total of 233,401 laboratory-confirmed cases. Of these, 1832 were FluCAN sentinel hospital influenza admissions, of which 122 cases (6.7%) were admitted directly to ICU, and over 308 influenza-associated deaths were notified to the NNDSS. Most deaths (99%) were associated with influenza A, of which 84% were unsubtyped, 12% were H3N2 and 3% were H1N1 subtypes. The median age of deaths notified was 82 years (range: 1 to 106 years).3 It is worth remembering that these numbers are likely to represent only a fraction of the actual influenza cases and deaths in Australia in 2022, as many people do not seek medical care when infected with influenza or are asymptomatic.

The 2023 influenza season

What can we expect in 2023 with influenza in Australia? One thing for certain is that there will be an influenza season in 2023; however, it is difficult to predict when it might begin and how severe it will be. This is especially so while we are in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic. The emergence of a new SARS-CoV-2 variant could cause another wave of infections that might interfere with the influenza season; this is a phenomenon known as ‘viral interference’. This effect might explain, somewhat, the rapid decline seen in the 2022 influenza season as COVID-19 cases increased.

To date, the NNDSS figures for 2023 show more laboratory-confirmed influenza cases in the first two months of 2023 than the same period in 2022 (8474 vs 79 cases, respectively), although case numbers in 2022 were artificially low because of COVID-19. So far, influenza case numbers this year are similar to those in pre-pandemic years, implying that the timing of the influenza season may also be similar to those of pre-pandemic years. This prediction could be quashed by outside factors, such as an influx of travellers with influenza B infections from the late season outbreaks currently occurring in Europe and the Pacific regions. Other factors that could influence the 2023 Australian influenza season include:

- the influenza subtypes that will circulate in 2023

- the timing of the start and peak of the season

- timing and coverage level of vaccinations

- remaining residual or herd immunity from infections or vaccinations that occurred in 2022, which may ameliorate but will not prevent an influenza epidemic.

Testing for influenza and other respiratory infections

When respiratory viruses co-circulate, there is also the potential for coinfections. To date, the number of coinfections with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza (often termed ‘flurona’) has been low and when they do occur, they have generally been no worse than a single infection; however, possible coinfections need to be monitored with each new SARS-CoV-2 variant that emerges. The TGA has recently approved a number of nasal swab rapid antigen tests (RATs) to self-test for COVID-19 and influenza A and B on the same test device.4 Their costs are similar to a COVID-19 only RAT ($10-15 per test). It should be remembered that, although these RATs perform well, they are not as sensitive or accurate as the gold-standard PCR or multiplex PCR testing, which tests for several respiratory pathogens (including SARS-CoV-2, influenza, RSV and possibly others). Multiplex PCR testing also provides information on which respiratory viruses are causing the disease burden throughout the winter period and guides public health responses, and should be preferentially requested whenever available.

Influenza vaccines and vaccination

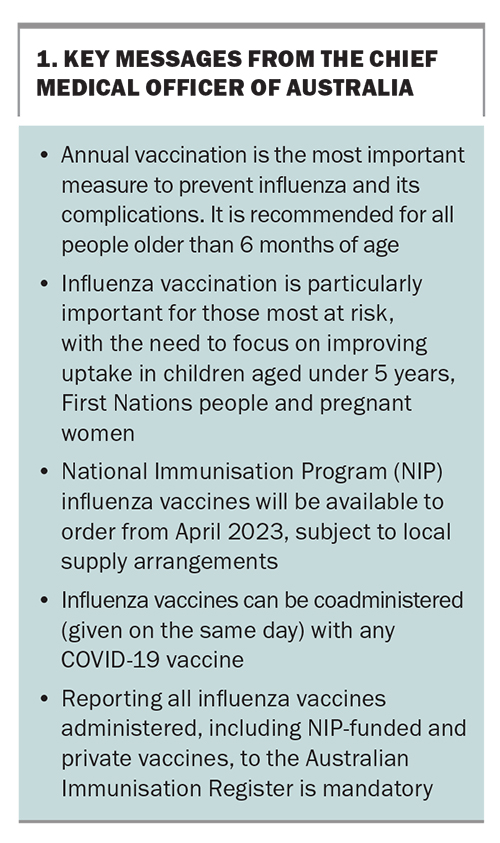

The Australian Chief Medical Officer, Dr Paul Kelly, wrote to all GPs on 22 February, 2023 outlining the National Immunisation Program (NIP) vaccine schedule for the 2023 influenza season. His key messages are reproduced in Box 1.

One change to note in the NIP schedule, published on 6 February 2023, is that influenza vaccination for children aged 6 months to under 5 years has been added to the main page of the schedule of childhood vaccinations.5 Although vaccinations for this age group have been covered under the NIP since 2020, this move equates influenza with other childhood vaccine recommendations, recognising the high burden of disease from influenza and the lower rate of annual vaccination within this age group in most seasons. For children under 6 months of age, maternal influenza vaccination has been shown to be safe and effective in providing protection to both the mother and child, is also recommended by The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI ) and is available under the NIP.

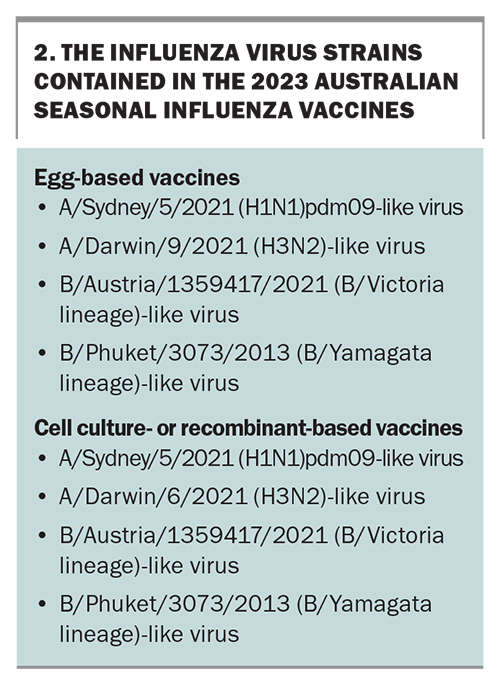

The composition of the vaccines available in 2023 differs from previous years, with an updated A(H1N1)pdm component to incorporate a more contemporary vaccine virus known as A/Sydney/5/2021 (or A/Sydney/ 5/2021-like virus) (Box 2). These Australian viruses appear in the recommended vaccines for the entire southern hemisphere because the WHO influenza laboratory tasked with the job of isolating influenza viruses suitable for influenza vaccine manufacture is located at the Doherty Institute in Melbourne. The vaccine production process starts with obtaining influenza virus-containing samples from all parts of Australia and the region, hence the regular occurrence of Australian-origin influenza viruses in the world’s influenza vaccines.

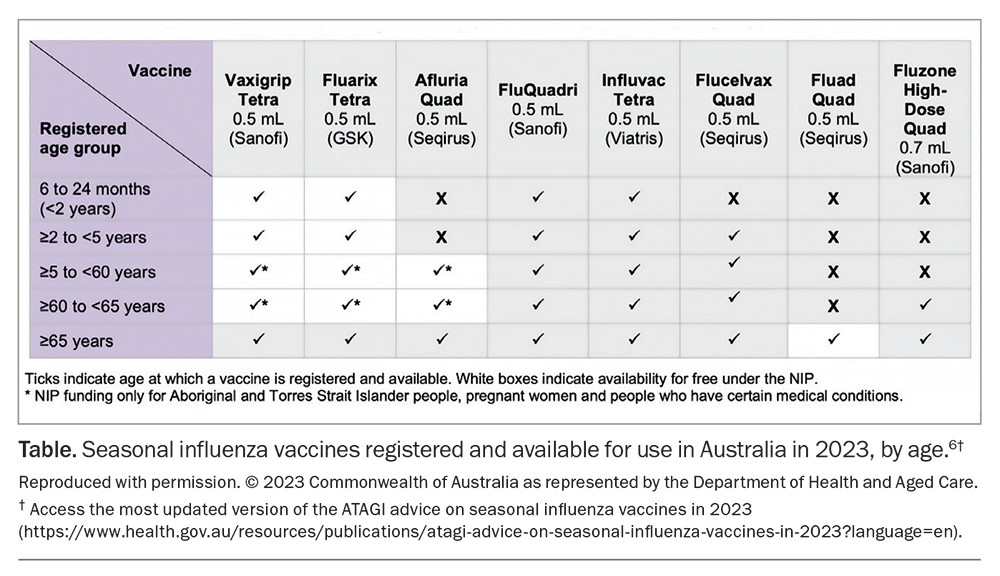

The influenza vaccines available in 2023, their recommended use for specific age groups according to ATAGI and availability under the NIP are presented in the Table.6 This summary makes it easy to choose the appropriate vaccine for each individual. The online version should be consulted for the most updated advice (https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/ atagi-advice-on-seasonal-influenza-vaccines-in-2023?language=en). Many vaccines are available and administered in pharmacies as well as in GP offices.

Influenza vaccination rates in Australia reached about 43% in 2022, with older people (65 years and over) the leading demographic at about 85% vaccination coverage, according to the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) database.7 However, only 37% of children under the age of 5 years were vaccinated, with a similar proportion of older children and adults (aged 5 to 64 years) vaccinated (36%) in 2022. Although the burden of influenza in older people is well understood, the burden in children, especially young children, is often underestimated. Hospitalisations and deaths due to influenza do occur in children (often in those with comorbidities) and children also play an important part in spreading influenza throughout the community.

Because the 2022 influenza season was early, many people were not vaccinated during the initial stages of the epidemic. Most states tried to increase vaccine uptake by offering free vaccine to people of all ages (6 months and older); however, this did not occur until June, when the epidemic was near its peak. Hence, the lesson from 2022 is to not delay vaccination; influenza vaccines are available as of April 2023 and GPs should encourage all patients to get vaccinated early, targeting April and May as the key months for influenza vaccinations in Australia.

Antiviral drugs, such as oseltamivir and zanamivir, can reduce symptoms of influenza when taken within 48 hours of symptom onset. These are only available on prescription.

Conclusion

Influenza will be back in 2023 but the timing and severity of the epidemic are unpredictable. Influenza vaccination is still the best measure for prevention or amelioration of disease and is suitable for people of all ages from 6 months and above. Several vaccines are available that offer higher protection to older individuals and to suit people with other issues, such as egg allergies. These vaccines are safe and have minimal side effects. Diagnostic methods for influenza are improving, with combination COVID-19 and influenza RATs now available; however, PCR testing (by a respiratory multiplex, if possible) is still the gold standard and should be requested whenever possible. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Barr holds shares in a vaccine producing company.

References

1. NSW Health. NSW COVID-19 weekly data overview. Epidemiological weeks 51 and 52, ending 31 December 2022. Available online at: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/covid-19/Documents/weekly-covid-overview-20221231.pdf (accessed March 2023).

2. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. Available online at: https://nindss.health.gov.au/pbi-dashboard/ (accessed March 2023).

3. Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian Influenza Surveillance Reports – 2022. Canberra; Department of Health and Aged Care, 2022. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/australian-influenza-surveillance-reports-2022?language=en (accessed March 2023).

4. Department of Health and Aged Care. First combination COVID-19 and influenza self-tests approved for Australia. Canberra; Therapeutic Goods Administration, 2022. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/products/covid-19/covid-19-tests/covid-19-rapid-antigen-self-tests-home-use/covid-19-rapid-antigen-self-tests-are-approved-australia (accessed March 2023).

5. Department of Health and Aged Care. National Immunisation Program schedule. Canberra; Department of Health and Aged Care, 2022. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-immunisation-program-schedule?language=en (accessed March 2023).

6. Department of Health and Aged Care. Statement on the administration of seasonal influenza vaccines in 2023. Canberra; Department of Health and Aged Care, 2023. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/atagi-advice-on-seasonal-influenza-vaccines-in-2023?language=en (accessed March 2023).

7. Australian Immunisation Register. Influenza (flu) immunisation data – 1 March to 4 December 2022. Canberra; Department of Health and Aged Care, 2022. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/influenza-flu-immunisation-data (accessed March 2023).