Borderline personality disorder: not what it used to be

Personality disorder occurs in up to one-quarter of people attending primary care, usually co-occurring with other mental and physical health needs. Evidence-based practical support is first-line treatment, with referral of patients for more specialised treatments only when needed.

Personality disorder is both clinically important and treatable. Yet, it is unjustifiably considered by some to be a controversial and untreatable condition, meaning that it still suffers from a crisis of legitimacy in the healthcare system. Personality disorder is present in up to one-quarter of people attending primary care.1 It is a leading cause of burden of disease in all age groups, premature mortality and enduring functional impairments over subsequent decades.2-6 By any measure, personality disorder is a severe mental disorder that should not be overlooked or ignored.

Classification and diagnosis

The way we think about personality disorder has changed. Historically, personality disorder was thought to be comprised of multiple, discrete categories or diagnoses (e.g. borderline, narcissistic, antisocial). Three decades of research has failed to support this categorical model and has demonstrated instead that personality disorder is a singular construct.7 This has led to the publication of two contemporary (and similar) models of personality disorder in the International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (ICD-11)8 and the Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (AMPD) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5).9

These two models have strong empirical support and offer improvements in clinical utility. Both models emphasise that what is common to all forms of personality disorder are difficulties in self-management (identity and self-direction) and interpersonal relationships (empathy and intimacy). Crucially, this approach identifies a clear, meaningful and changeable treatment target, namely self- and interpersonal functioning, and is potentially less stigmatising.10

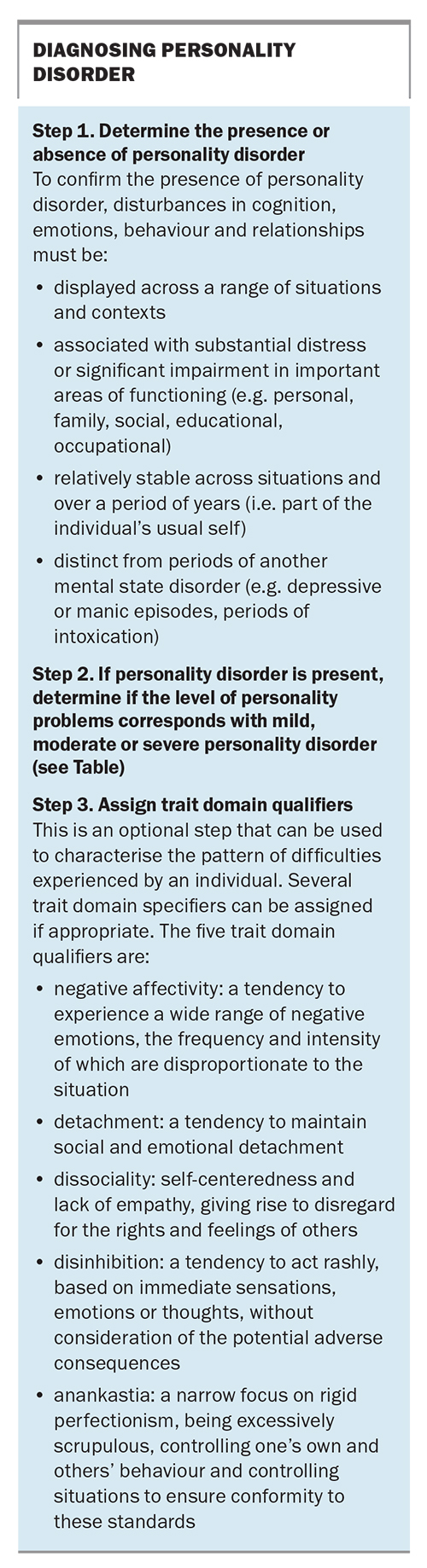

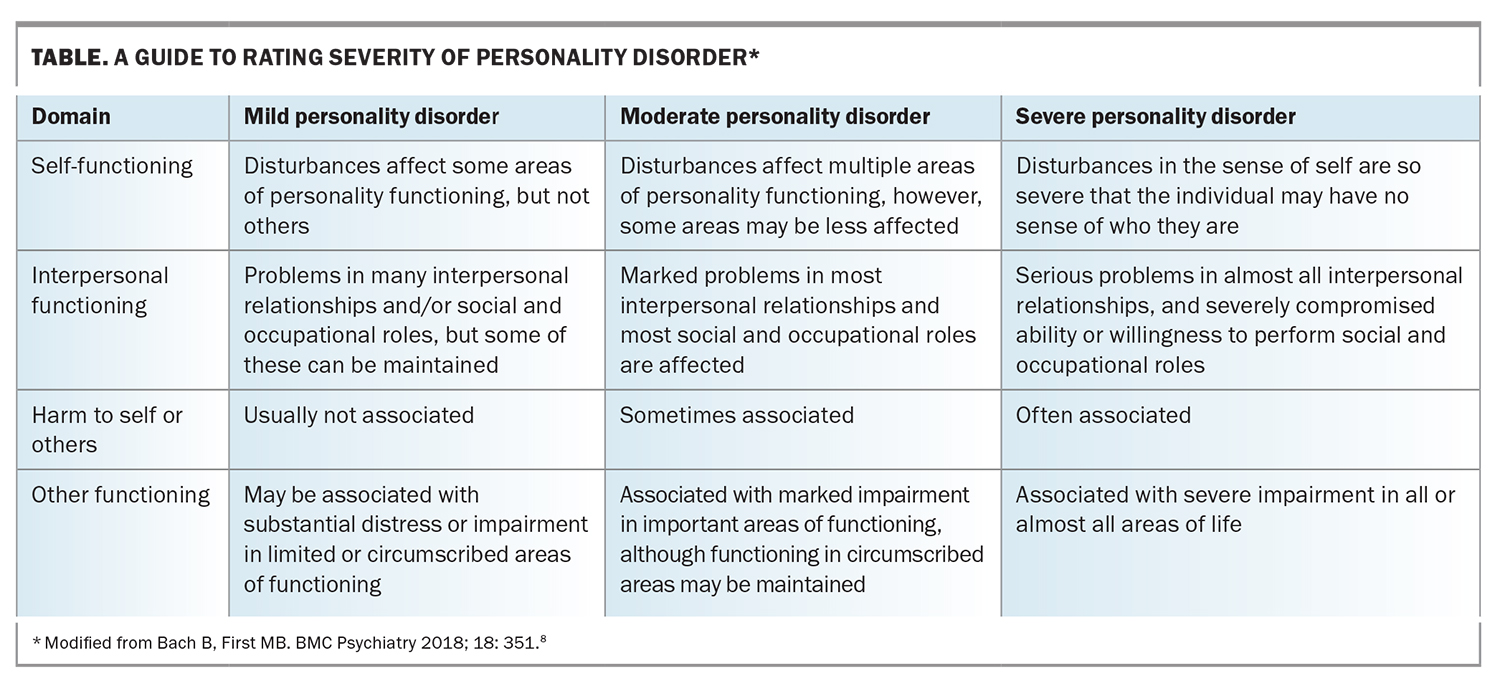

The ICD-11 and DSM-5 AMPD follow a similar diagnostic process. First, personality disorder is assessed as being present and then second, rated as mild, moderate or severe. Personality disorder describes a person’s usual self. This long-standing pattern of difficulties in self- and interpersonal functioning differentiates personality disorder from the more episodic nature of mental state disorders, such as depression. For example, someone with personality disorder might present with enduring problems in a number of relationships, and express difficulty in regulating their emotions across a variety of situations (see Box and Table). Third, there is an optional process to describe the ‘flavour’ of personality disorder by using trait descriptors. For example, a clinician might specify the presence of negative affectivity to describe the tendency to experience a wide range of negative emotions, the frequency and intensity of which are disproportionate to the situation. The term borderline personality disorder (BPD) lives on in ICD-11 as a specifier, in part to provide continuity for mental health service providers and policymakers, while they adjust to the new dimensional model. Evidence indicates that BPD is most representative of all personality disorders and the terms BPD and severe personality disorder are largely synonymous. This also means that many decades of research on BPD remains relevant to our understanding of personality disorder.

Aetiology

Contemporary aetiological theories identify genetic, biological and/or psychological vulnerabilities in areas such as emotion regulation, social cognition, or self and identity development that interact with the environment to disrupt healthy personality development.11 Importantly, none of these temperamental, biological and environmental risk factors is specific for personality disorder, and some or all aspects of the aetiological pathway are shared with many other mental disorders.

The heritability of personality disorder is slightly greater than for major depression.12 Environmental risk factors include impairments in early maternal bonding, harsh or insensitive parenting, physical maltreatment and/or maternal negative expressed emotion, bullying victimisation, and concurrent or subsequent disruptions in self-control, mentalising, emotion regulation and self-representation. Although common among people with personality disorder, childhood adversity (such as abuse and neglect) is a nonspecific risk factor, associated with almost every major mental disorder, and is neither necessary nor sufficient for the development of personality disorder. About 30% of adults living with BPD report no childhood adversity, suggesting that there are both traumatic and nontraumatic pathways to developing the disorder.13

The neurobiology of personality disorder is less well understood, with research suggesting that (pre-)frontal regulatory deficits inhibit top-down control of emotions and impulses, which in turn lead to emotional dysregulation, impulsive risk-taking and self-harm behaviours.11 Alterations in the peripheral stress response systems and/or the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in the aetiology of BPD might also be implicated.

Clinical onset and early intervention

Personality disorder has its clinical onset and peak prevalence in adolescence and early adulthood.14 Despite international consensus that personality disorder can be reliably diagnosed in young people (aged 12 to 25 years),14 many clinicians remain reluctant to diagnose personality disorder in people under 18 years of age. Withholding of the diagnosis and misdiagnosis are common, meaning that appropriate treatment is often delayed, or that inappropriate treatments are commenced, both of which can result in worsening of problems.

Early intervention in youth mental health refers to the stage of illness, rather than a person’s age or developmental period.15 Such clinical staging models acknowledge the dimensional nature of personality disorder, its co-occurrence with symptoms from other disorders (e.g. depression or anxiety), and the distress and disruption that such psychopathology can cause among young people, even before the threshold for a specific diagnosis has been reached.11 Features of personality disorder tend to become more accentuated from puberty onwards, peaking in young adulthood, before attenuating over time.16 However, this symptomatic improvement does not necessarily translate into improvements in functioning. Personality difficulties during this developmental epoch can significantly disrupt the transition into adulthood, interrupting essential skill acquisition and affecting adult social integration and role functioning.11

Treatment and management

Psychosocial intervention is the first-line treatment for personality disorder. Although medications are not indicated for people with personality disorder per se, they can be effective (and are often used) for those with common, co-occurring disorders, such as depression or anxiety. However, these are not a substitute for addressing the personality disorder itself. It is possible that poor depression treatment outcomes in people with personality disorder are due to inadequate treatment of the depression.17

Specialised psychotherapies have been consistently shown to be more effective than treatment as usual for reducing symptom severity.18 No one psychotherapy appears to outperform the others (despite claims from some brand ambassadors). Although individual psychotherapies that are designed for treating personality disorder are effective, every GP knows that access to these services is difficult, and treatment is usually lengthy and costly.

Increasing evidence suggests that structured clinical care, involving less complex individual sessions, is as effective as brand name therapies. This approach, including ‘good clinical care’ in young people and ‘general psychiatric management’ in adults, uses psychoeducation, practical case management and problem solving, and has been shown to improve outcomes in individuals with personality disorder.19,20 A recent 18-month clinical trial involving young people with severe personality disorder found that individual psychotherapy was not superior to pragmatic treatment (including time-limited clinical case management and treatment of co-occurring problems), which did not involve any individual psychotherapy, for improving psychosocial functioning and interpersonal problems, as well as depression and suicidal thoughts.21 This trial provides proof of concept for a treatment that might be suitable for implementation in primary care, where most people with personality disorder present for help. Arguably, this is what GPs have always done, but this trial suggests that GP-delivered, structured, considered and practical clinical care is not a ‘stop gap’ treatment while waiting for specialist services. Rather, it is effective management for people with personality disorder, mitigating the issue of restricted availability of services and allowing more people access to appropriate and timely care.

Families

Although family environment is implicated in the aetiology of personality disorder, it is scientifically unwarranted and clinically misguided to reductively blame and alienate families, as this often exacerbates problems, especially by disenfranchising families from treatment. If present, evidence suggests that family environmental problems are often multigenerational and that families of people with personality disorder also experience high levels of distress and negative experiences of caregiving.22-24 Families and others who care for people with personality disorder are often important supporters of people with personality disorder, and potential allies in care planning. Early family engagement and psychoeducation are important components of treatment planning. Needless to say, if family violence or other forms of abuse are present, this must be swiftly acted upon.

Ignorance, prejudice and discrimination

Stigma (comprising ignorance, prejudice and discrimination) is perhaps the greatest barrier to improving the lives of people with personality disorder. Unfortunately, this is most often enacted by healthcare professionals, especially mental health clinicians, who have more negative attitudes towards people with personality disorder than towards those with other mental disorders.13,25 Misinformation and outdated beliefs regarding the aetiology and treatability of people with personality disorder need to be challenged in our own practice and among colleagues. Sometimes, stigma is implicit in the focus on the name of the disorder, especially the term BPD, epistemological concerns about personality disorder itself or whether intervention is even justifiable.26,27 We contend that these problems are not unique to personality disorder, and we argue for reforming clinical cultures, so that open, honest and evidence-based dialogue can be achieved. The aim of this is to dispel damaging myths about personality disorder and to instil hope among those living with the disorder and those who care for and about them. All healthcare professionals, people with personality disorder and those who care for and support them should have a stake in this conversation.

Conclusion

Personality disorder is common in primary care. Despite the associated distress, persistent functional impairment and premature mortality, appropriate and timely treatment is inaccessible for most people. Adopting the new ICD-11 and DSM-5 AMPD diagnostic systems might improve the rate of diagnosis and treatment of people with personality disorder in primary care settings. Evidence increasingly points to the effectiveness of practical, scalable models of care that include psychoeducation, practical support and attention to co-occurring mental and physical health conditions. These treatments can improve the lives of people with personality disorder. Reforming clinical cultures to speak out against bigotry in all its forms, and to be welcoming and adaptable to the needs of people with personality disorder is a challenge that every healthcare professional should embrace. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None

References

1. Moran P, Jenkins R, Tylee A, Blizard R, Mann A. The prevalence of personality disorder among UK primary care attenders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102: 52-57.

2. GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022; 9: 137-150.

3. Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS One 2013; 8: e55176.

4. Wertz J, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Borderline symptoms at age 12 signal risk for poor outcomes during the transition to adulthood: findings from a genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020; 59: 1165-1177.e2.

5. Hastrup LH, Jennum P, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J, Simonsen E. Welfare consequences of early-onset borderline personality disorder: a nationwide register-based case-control study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2022; 31: 253-260.

6. Winograd G, Cohen P, Chen H. Adolescent borderline symptoms in the community: prognosis for functioning over 20 years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008; 49: 933-941.

7. Newton-Howes G, Newton-Howes G, Clark LA, Clark LA, Chanen A, Chanen AM. Personality disorder across the life course. Lancet 2015; 385: 727-734.

8. Bach B, First MB. Application of the ICD-11 classification of personality disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2018; 18: 351.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

10. Sharp C. Personality disorders. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 916-923.

11. Chanen AM, Sharp C, Nicol K, Kaess M. Early intervention for personality disorder. Focus 2022; 20: 402-408.

12. Bohus M, Stoffers-Winterling J, Sharp C, Krause-Utz A, Schmahl C, Lieb K. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2021; 398: 1528-1540.

13. Chanen AM. Bigotry and borderline personality disorder. Australasian Psychiatry 2021; 29: 579-580.

14. Chanen A, Sharp C, Hoffman P, Global Alliance for Prevention and Early Intervention for Borderline Personality Disorder. Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: a novel public health priority. World Psychiatry 2017; 16: 215-216.

15. McGorry PD, Mei C. Clinical staging for youth mental disorders: progress in reforming diagnosis and clinical care. Annu Rev Dev Psychol 2021; 3: 15-39.

16. Videler AC, Hutsebaut J, Schulkens JEM, Sobczak S, van Alphen SPJ. A life span perspective on borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2019; 21: 51.

17. Mulder RT. Personality pathology and treatment outcome in major depression: a review. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 359-371.

18. Storebø OJ, Stoffers-Winterling JM, Völlm BA, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 5: CD012955.

19. Gunderson J, Masland S, Choi-Kain L. Good psychiatric management: a review. Curr Opin Psychol 2018; 21: 127-131.

20. Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McCutcheon LK, et al. Early intervention for adolescents with borderline personality disorder using cognitive analytic therapy: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 193: 477-484.

21. Chanen AM, Betts JK, Jackson H, et al. Effect of 3 forms of early intervention for young people with borderline personality disorder: The MOBY Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2022; 79: 109-119.

22. Bailey RC, Grenyer BFS. Burden and support needs of carers of persons with borderline personality disorder: a systematic review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2013; 21: 248-258.

23. Seigerman MR, Betts JK, Hulbert C, et al. A study comparing the experiences of family and friends of young people with borderline personality disorder features with family and friends of young people with other serious illnesses and general population adults. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul 2020; 7: 17.

24. Cotton SM, Betts JK, Eleftheriadis D, et al. A comparison of experiences of care and expressed emotion among caregivers of young people with first-episode psychosis or borderline personality disorder features. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2022; 56: 1142-1154.

25. McKenzie K, Gregory J, Hogg L. Mental health workers’ attitudes towards individuals with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder: a systematic literature review. J Pers Disord 2022; 36: 70-98.

26. Hartley S, Baker C, Birtwhistle M, et al. Commentary: bringing together lived experience, clinical and research expertise - a commentary on the May 2022 debate (should CAMH professionals be diagnosing personality disorder in adolescence?). Child Adolesc Ment Health 2022; 27: 246-249.

27. Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Looi JC, Mulder R. Adolescent borderline personality disorder: does early intervention "bend the curve"? Australas Psychiatry 2022; 30: 698-700.