Keeping their hearts in mind – cardiometabolic health and severe mental illness

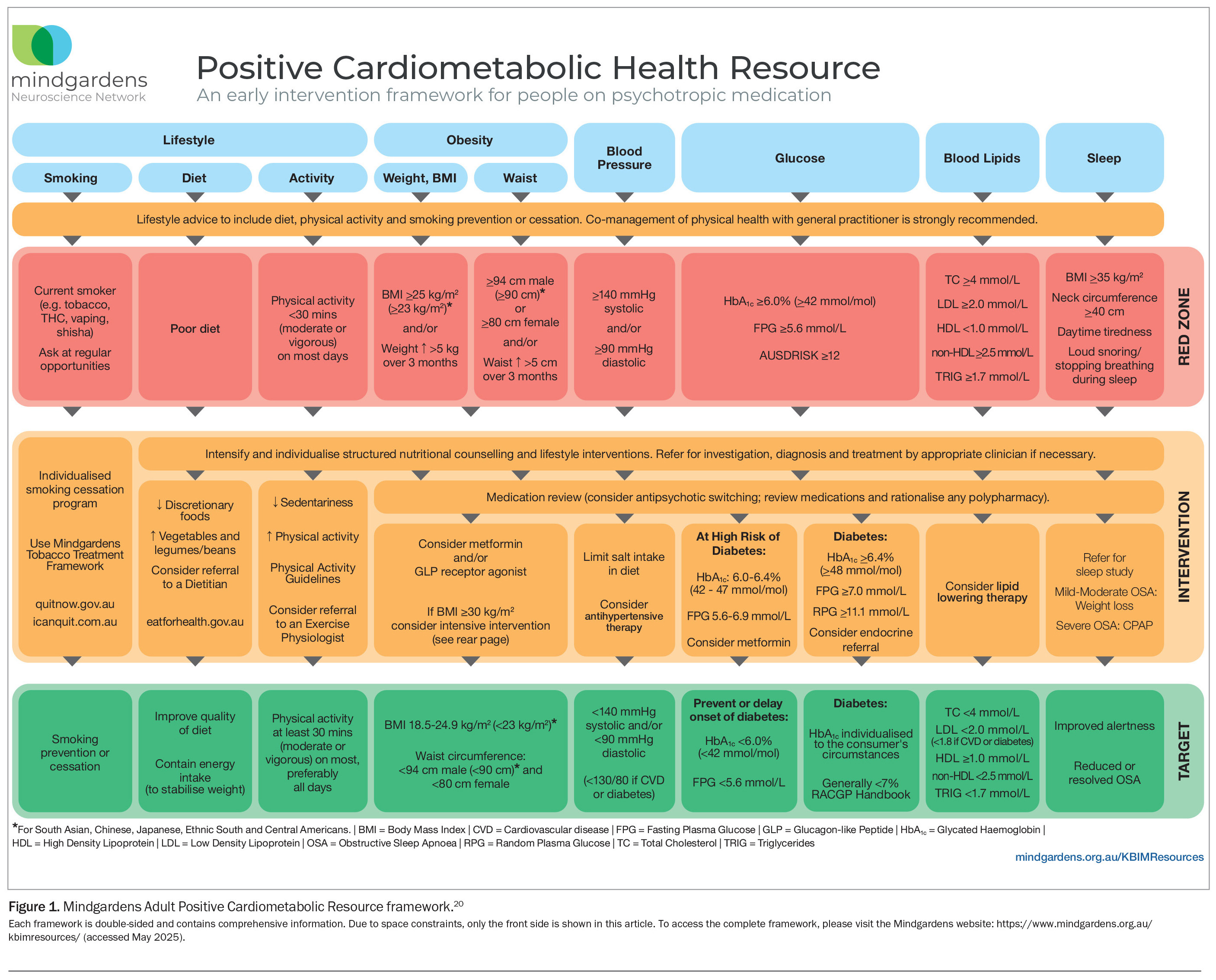

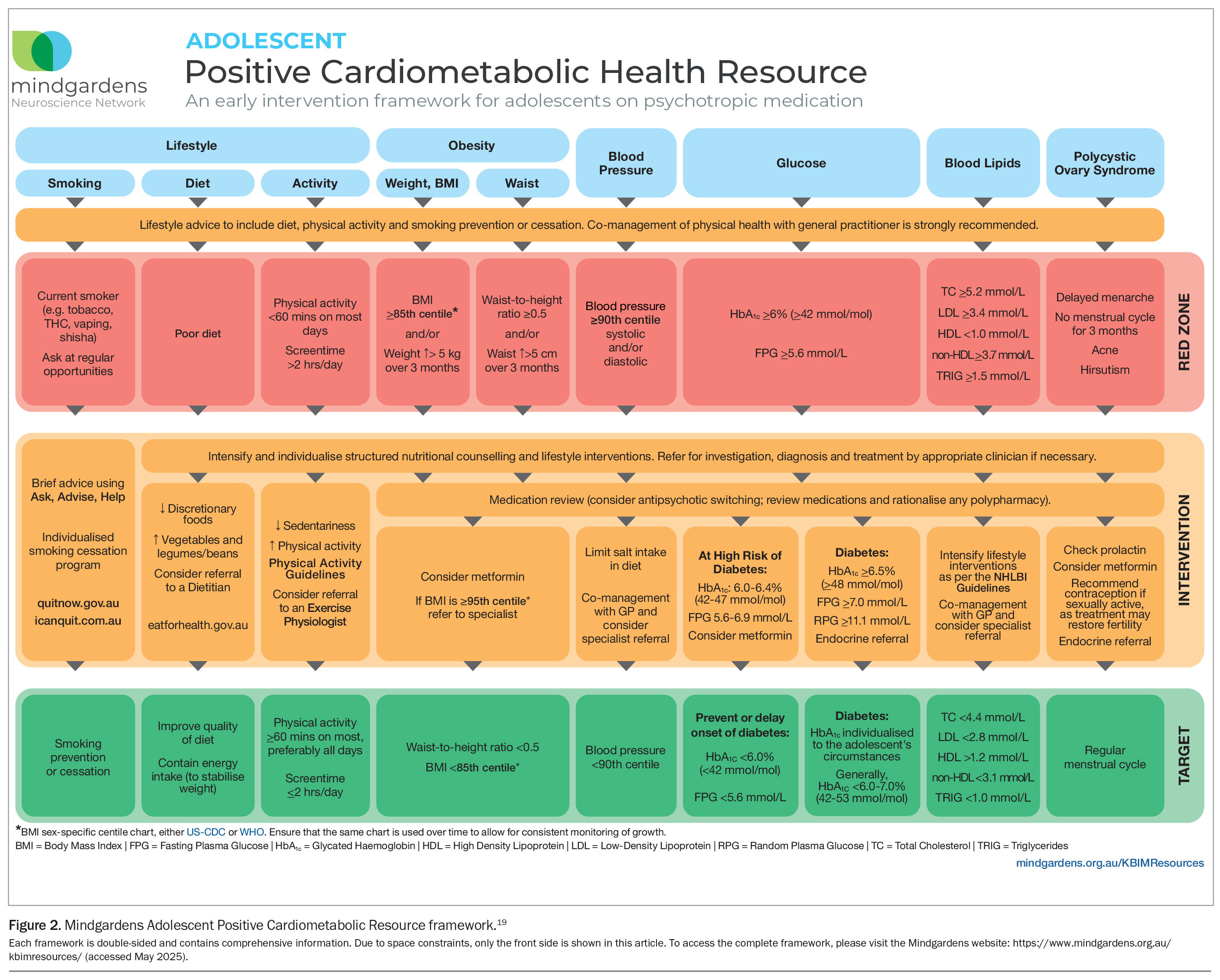

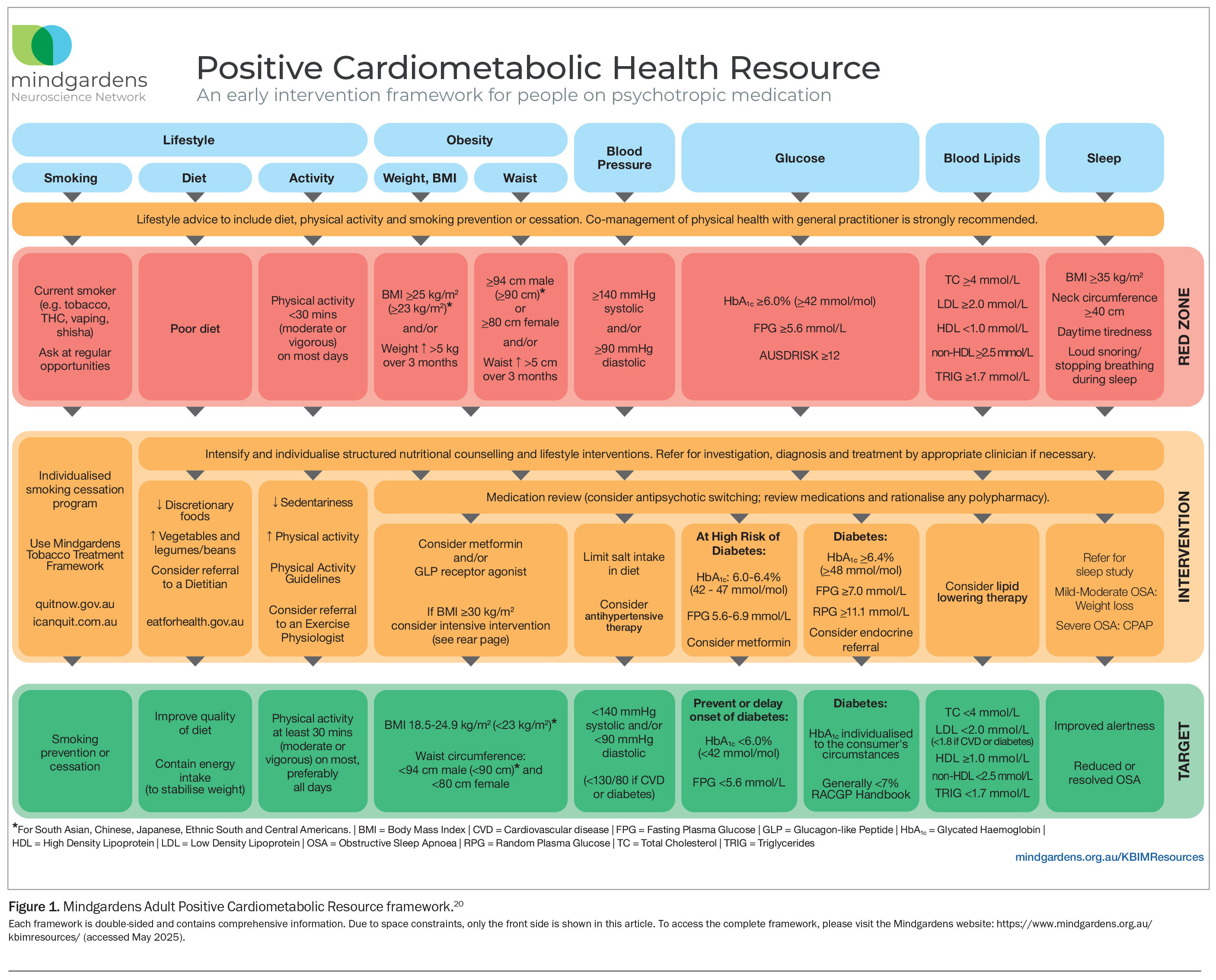

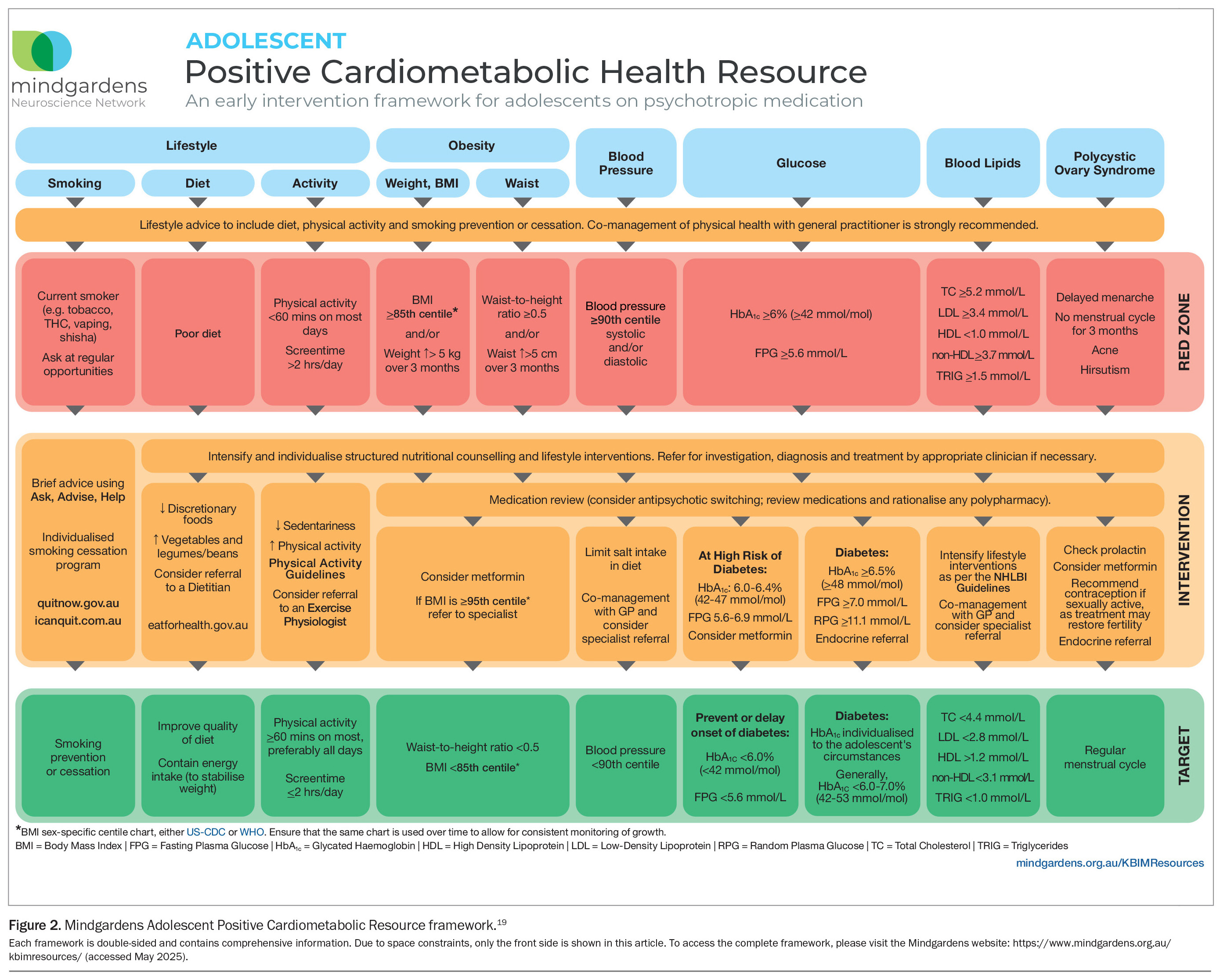

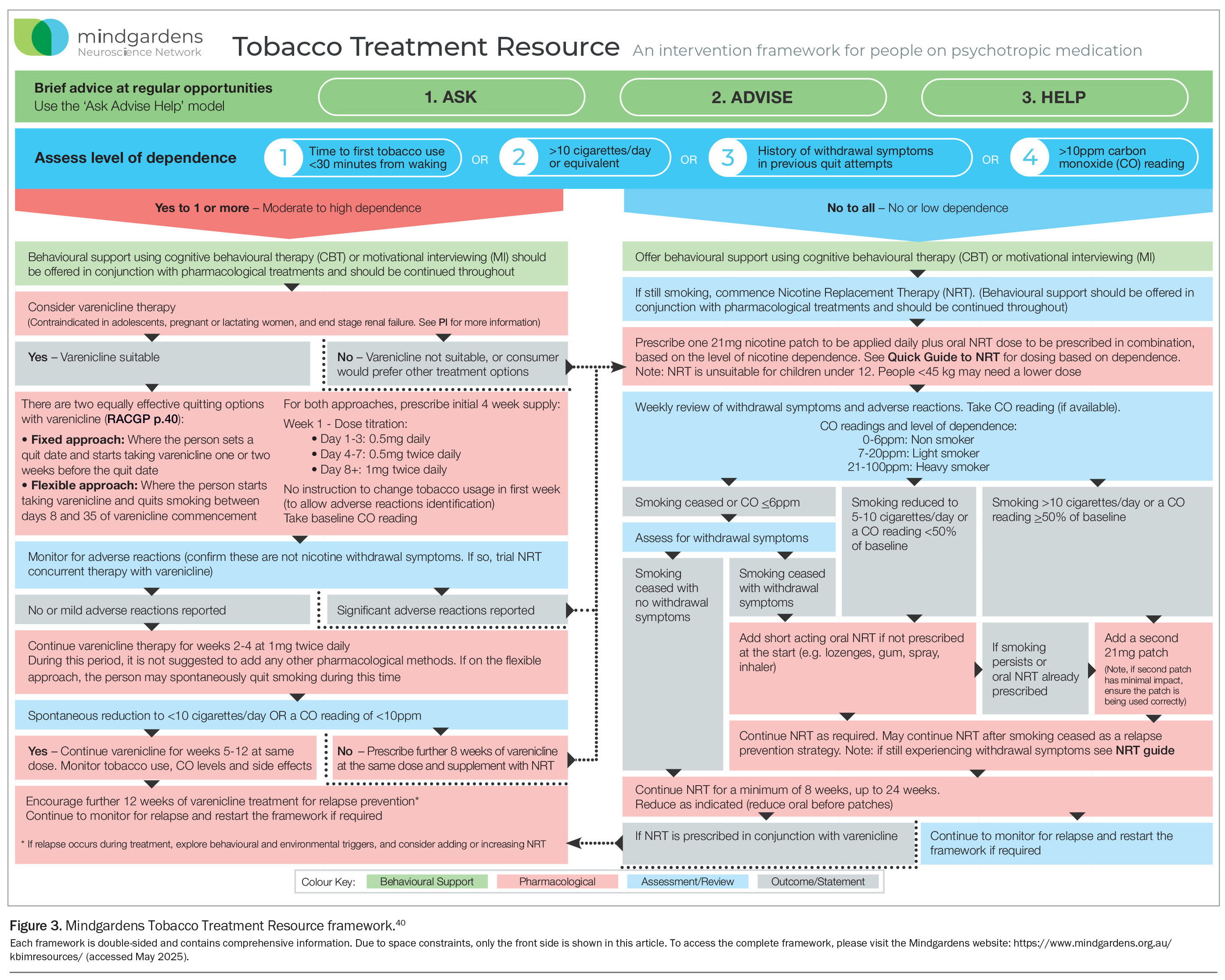

Individuals with severe mental illness are more likely to develop cardiovascular disease and metabolic abnormalities than the general population. The Mindgardens Adult and Adolescent Positive Cardiometabolic Resource frameworks incorporate screening and intervention points for physical health in people with severe mental illness. Tobacco smoking is also more common in this population, and the Mindgardens Tobacco Treatment Resource framework provides appropriate smoking cessation guidance.

- People with severe mental illness have a 75% higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease and a considerably shorter life expectancy than those without severe mental illness.

- Metabolic abnormalities often occur early in the course of a severe mental illness and its treatment, with causes including medication side effects and modifiable cardiovascular risk factors.

- Regular screening and multidisciplinary management addressing both mental and physical health are essential. However, many barriers to these exist in general practice, specialist and mental health settings.

- The Mindgardens Adult and Adolescent Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource frameworks were designed to promote safe and effective clinical decision-making, extend clinicians’ knowledge of lifestyle interventions and screening, and help healthcare professionals treat physical health in people with severe mental illness.

- Up to 80% of individuals with severe mental illness engage in tobacco smoking, and standard smoking cessation guidance may not suffice because of heightened cognitive demands and additional barriers in this population, including socioeconomic disadvantage.

- The Mindgardens Tobacco Treatment Resource framework provides smoking cessation interventions suited for people with severe mental illness.

Severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, are persistent conditions, for which about one in 300 people in Australia receive treatment each month.1 People with severe mental illness have a considerably shorter life expectancy than the general population, predominantly because of the presence of physical health conditions, which constitute about 70% of all deaths in people with severe mental illness.2 In particular, people with severe mental illness have a 75% higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) and an 85% higher risk of CVD-specific mortality compared with the general population.3 This equates to one-quarter of deaths associated with schizophrenia and one-third of deaths associated with bipolar disorder.4,5

Metabolic abnormalities, such as hypertension, obesity, dyslipidaemia and elevated blood glucose levels, occur early in the course of a severe mental illness and its treatment, leading to metabolic syndrome (a precursor to CVD) and all-cause mortality that occurs at rates up to twice as high in people with severe mental illness compared with the general population.6-8 The underlying drivers of these metabolic abnormalities are multifactorial, and examples include medication side effects (especially of antipsychotic medications), high rates of smoking, physical inactivity and poor-quality dietary intake.9 Alongside an increased prevalence of nearly all modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, other issues contributing to the mortality gap include disparities in healthcare access and quality and the direct effects of the illness (e.g. cognitive impairments).10,11

Given the increased risk of metabolic syndrome and CVD, regular screening and comprehensive, multidisciplinary management addressing both medical and behavioural aspects is essential.9,12,13 However, in reality, people with a mental illness, particularly those with schizophrenia, undergo inadequate screening and receive lower-quality treatment for CVD compared with people without mental illness.14

Barriers to providing adequate screening and management are often encountered in general practice, specialist and mental health settings.10,15-17 For healthcare professionals, including GPs and specialists, barriers include:

- a limited understanding of the physical health needs of this population

- a lack of co-ordination between primary care and mental health care

- the requirement for additional appointments

- negative attitudes

- financial obstacles, such as co-payments.10,17

Obstacles to conducting physical health screenings within mental health service settings include:

- diagnostic overshadowing

- a limited awareness of physical health requirements

- a lack of confidence in screening

- hesitation in recommending interventions aimed at mitigating the risk of metabolic syndrome.15,16

The 2021 Being Equally Well National Policy Roadmap details a path forward to providing better physical healthcare and supporting longer lives for people with severe mental illness in Australia.18 Importantly, the roadmap highlights positive cardiometabolic health frameworks, as a ‘Don’t just screen; intervene’ approach, incorporating evidence-based pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions.

The Mindgardens Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource frameworks

The Mindgardens Adolescent and Adult Positive Cardiometabolic Resource frameworks are based on the Adult Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource first developed in 2010, which has been adapted in nine countries, including the United Kingdom.19-22 The frameworks, which are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, were designed to promote safe and effective prescribing and clinical decision-making, extend clinicians’ knowledge of lifestyle interventions and screening, and rapidly build the capacity of staff in treating the physical health of people with severe mental illness. Further details are provided in the Box.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evidence and usage guidelines for the Mindgardens Adolescent and Adult Positive Cardiometabolic Resource frameworks and the Tobacco Treatment Resource framework. These frameworks incorporate screening and intervention points for cardiometabolic abnormalities, empowering mental health clinicians, GPs and other professionals to recognise and address these issues in individuals with severe mental illness.

The Mindgardens Adult and Adolescent Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource frameworks serve as a guide and practical tool for healthcare professionals in their clinical practice. These resources emphasise person-centred care, encouraging shared decision-making between people with severe mental illness and clinicians by offering a framework for structured and individualised conversations.

Frequency of assessment and monitoring

The initiation of antipsychotic medication is associated with a heightened risk of metabolic disturbances and represents a critical period for intervention.23 On starting antipsychotic medication, a baseline lifestyle assessment should be conducted, encompassing the person’s physical health history, a review of their current lifestyle behaviours, anthropometric measures and investigations of metabolic blood pathology (Figure 1). These assessments should be revisited at three-month intervals during the first year after starting antipsychotic medication and at six-month intervals thereafter. Additionally, during the first six to eight weeks, the person’s body weight should be recorded and lifestyle factors reviewed on a weekly basis. In this initial period, all people with severe mental illness should be offered guidance on healthy lifestyle behaviours, which should include advice on diet, physical activity and preventing or quitting smoking where relevant.

Education and support should be offered through a motivational and person- centred approach that acknowledges the individual’s health goals and perspectives, and can also involve their carers and families. Collaborative management of physical health with a GP is strongly recommended.

‘Don’t just screen; intervene’

The ‘red zone’ in the frameworks lists several metabolic syndrome phenotypes, which act as trigger points for increased screening and intervention. At the outset, practitioners should enhance and personalise structured nutritional counselling and lifestyle interventions. Guidelines are provided for examination, diagnosis and treatment by suitable lifestyle clinicians if deemed necessary. A medication review is also included for consideration, encompassing antipsychotic switching, the assessment of medications and the streamlining of any polypharmacy.

Following this, for people with severe mental illness presenting with obesity, consideration should be given to the use of metformin or a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist.24,25 For elevated blood pressure or hypertension, recommendations should involve limiting salt intake in the diet and considering antihypertensive therapy.26 A review of metabolic pathology, including abnormal blood glucose and lipid results, should consider metformin prescription or referral to an endocrinology specialist and initiation of lipid-lowering therapy.27,28

Specific evidence-based lifestyle interventions are advised, encompassing an individualised smoking cessation program, nutritional and dietary recommendations, prescribed physical activity and targeted interventions including sleep studies and continuous positive airway pressure machines to improve sleep quality.29-32 Multidisciplinary lifestyle support should be offered, and referrals made where appropriate, and should include exercise physiologists, dietitians and occupational therapists.

Adolescent version

The rapid and clinically significant weight gain associated with the initiation of antipsychotic medication poses a risk of premature development of cardiometabolic risk factors in young individuals experiencing their first episode of psychosis.33,34 Prevention and early intervention for cardiometabolic health in adolescents who are receiving these treatments are vital for both short- and longer-term outcomes and as such, tailored interventions have been developed in an adolescent-specific framework (Figure 2). Primarily, the recommendations closely mirror those of the adult version, with minor variations in prescription dosages and removal of some pharmacological interventions, with instead referral to a relevant specialist. Notable distinctions encompass screening and intervention for polycystic ovary syndrome, suggestions for heightened physical activity and reduced screen time, and the incorporation of evidence-based thresholds for anthropometry and metabolic pathology.

Mindgardens Tobacco Treatment Resource framework

Considering the alarmingly high rates of tobacco smoking within this population, with up to 80% of individuals with severe mental illness engaging in smoking, it is of utmost importance to enhance support for those seeking to quit.35 Standard recommendations tailored for the general population may not be appropriate for individuals with severe mental illness because of the heightened cognitive demands and additional barriers they may face (e.g. socioeconomic disadvantage and lack of support from family, peers and healthcare providers).36 Despite these challenges, most people with severe mental illness who smoke tobacco express a desire to quit and seek support in doing so.37-39

To assist health practitioners in offering quit interventions suited to the requirements of individuals with severe mental illness, a Tobacco Treatment Framework (Figure 3)has been developed by Mindgardens to offer evidence-based guidance.40 It recommends varenicline as a safe and effective first-line treatment for dependent smokers in this population, unless otherwise contraindicated.41 These tailored interventions encompass strategies for delivering behavioural support alongside pharmacological aids such as nicotine replacement therapy and varenicline. Additionally, the resource offers insights into considerations regarding interactions with psychotropic medications and instructions for accessing government-subsidised smoking cessation provisions.

Integration of screening as standard practice

Enhanced monitoring and intervention strategies for cardiometabolic disease risk factors are essential for individuals with severe mental illness to alleviate the alarmingly high rates of morbidity and mortality in this population. The implementation of screening tools to identify physical health concerns in individuals with severe mental illness remains a high priority, as recognised in international evidence-based documents and reflected in Australian government policy guidelines.9,42 Ensuring the physical wellbeing of individuals with severe mental illness is emphasised in Australian government guidelines such as the Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan.43 To work towards achieving this, mental and physical healthcare need to be integrated across diverse sectors, encompassing public, private (including general practice) and community domains. Essential guidance for implementation is detailed in influential documents like the Equally Well National Consensus Statement, which has garnered endorsement from national and state government health organisations and peak bodies including the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.44

To address the ‘scandal of premature mortality’ and the inequities in healthcare provision among people in this vulnerable group, a comprehensive health system approach to metabolic screening and intervention is required. 9,22,45 Professionals in primary care, specialist services and mental health service settings must incorporate physical health screening as an integral element of essential healthcare, with GPs and cardiometabolic specialists poised to play a key role in providing high-quality and early intervention.46 However, to effectively implement such practices, additional training, education and access to evidence-based resources are necessary.10 Ensuring person-centred care is paramount and involves tailoring discussions to the individual’s needs and preferences, facilitating shared decision-making. This approach emphasises the importance of active involvement and empowerment of the person in their healthcare journey. To achieve this, communication between and appropriate referrals to primary healthcare, specialist care and mental health teams are essential. Through a collaborative approach, these healthcare specialists can pool their expertise and resources to provide comprehensive support to the individual. This collaborative effort ensures that the person receives holistic care that addresses both their physical and mental health needs.

Conclusion

The Mindgardens Adult and Adolescent Positive Cardiometabolic Resource frameworks are offered as practical tools for practitioners as an initial step to facilitate early intervention and to work towards improving the health outcomes of people with severe mental illness. In addition, The Mindgardens Tobacco Treatment Resource framework provides appropriate smoking cessation guidance for this population. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Morgan VA, McGrath JJ, Jablensky A, et al. Psychosis prevalence and physical, metabolic and cognitive co-morbidity: data from the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Psychol Med 2014; 44: 2163-2176.

2. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 334-341.

3. Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry 2017; 16: 163-180.

4. Biazus TB, Beraldi GH, Tokeshi L. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among people with bipolar disorder: a large-scale systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry 2023; 28: 2508-2524.

5. Correll CU, Solmi M, Croatto G. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry 2022; 21: 248-271.

6. Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR. Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP study. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71: 1350-1363.

7. Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 1113-1132.

8. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2015; 14: 339-347.

9. Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6: 675-712.

10. Goldfarb M, De Hert M, Detraux J. Severe mental illness and cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022; 80: 918-933.

11. Kalinowska S, Trześniowska-Drukała B, Kłoda K, et al. The association between lifestyle choices and schizophrenia symptoms. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 165.

12. Castle DJ, Galletly CA, Dark F. The 2016 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. MJA 2017; 206: 501-505.

13. Shiers D, Curtis J. Cardiometabolic health in young people with psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry 2014; 1: 492-494.

14. Solmi M, Fiedorowicz J, Poddighe L. Disparities in screening and treatment of cardiovascular diseases in patients with mental disorders across the world: systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 observational studies. Am J Psychiatry 2021; 178: 793-803.

15. Glowacki K, Weatherson K, Faulkner G. Barriers and facilitators to health care providers’ promotion of physical activity for individuals with mental illness: a scoping review. MENPA 2019; 16: 152-168.

16. Happell B, Scott D, Platania-Phung C. Perceptions of barriers to physical health care for people with serious mental illness: a review of the international literature. IMHN 2012; 33: 752-761.

17. Waterreus A, Morgan VA. Treating body, treating mind: the experiences of people with psychotic disorders and their general practitioners – findings from the Australian National Survey of High Impact Psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2018; 52: 561-572.

18. Calder RV, Dunbar JA, de Courten MP. The Being Equally Well national policy roadmap: providing better physical health care and supporting longer lives for people living with serious mental illness. Med J Aust 2022; 217 (Suppl 7): S3-S6.

19. Watkins A, Gould P, Fibbins H. Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource: an early intervention framework for people on psychotropic medication (adolescent version). Sydney: Mindgardens Neuroscience Network; 2024. Available online at: https://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/entities/publication/e6d003a3-52c8-4700-9cf7-ecdc5bc0d020 (accessed May 2025).

20. Watkins A, Gould P, Fibbins H. Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource: an early intervention framework for people on psychotropic medication (adult version). Sydney: Mindgardens Neuroscience Network; 2024. Available online at: https://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/entities/publication/41171139-007c-467b-bb52-d910cba0cb0c (accessed May 2025).

21. Curtis J, Newall HD, Samaras K. The heart of the matter: cardiometabolic care in youth with psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2012; 6: 347-353.

22. Shiers D, Rafi I, Cooper S, Holt R. Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource: an intervention framework for patients with psychosis and schizophrenia. 2014 update. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014. Available online at: https://www.hpft.nhs.uk/media/1711/positive-cardiometabolic-health-resource-june-2014.pdf (accessed May 2025).

23. Sepúlveda-Lizcano L, Arenas-Villamizar VV, Jaimes-Duarte EB. Metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic drug therapy: a systematic review. EJIHPE 2023; 13: 1505-1520.

24. Fitzgerald I, O’Connell J, Keating D. Metformin in the management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain in adults with psychosis: development of the first evidence-based guideline using GRADE methodology. BMJ Mental Health 2022; 25: 15-22.

25. Khaity A, Mostafa Al-dardery N, Albakri K. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor-agonists treatment for cardio-metabolic parameters in schizophrenia patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry 2023; 14: 1153648.

26. Gabb GM, Mangoni AA, Anderson CS. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults – 2016. MJA 2016; 205: 85-89.

27. Diabetes Australia. Management of type 2 diabetes: a handbook for general practice. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2020. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/getattachment/010e971d-81a6-435e-90d0-8bb15eff8f7e/Management-of-type-2-diabetes-A-handbook-for-general-practice-Clinical-summary.pdf.aspx (accessed May 2025).

28. Australian Heart Foundation. Practical guide to pharmacological lipid management. Melbourne: Heart Foundation; 2024. Available online at: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/Bundles/Heart-Health-Check-Toolkit/pharmacological-lipid (accessed May 2025).

29. National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian dietary guidelines. Canberra: Australian Government; 2021. Available online at: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/ (accessed May 2025).

30. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Physical activity and exercise guidelines for all Australians: for adults (18-64 years). Canberra: Australian Government; 2021. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/physical-activity-and-exercise/physical-activity-and-exercise-guidelines-for-all-australians/for-adults-18-to-64-years (accessed May 2025).

31. Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-Bang questionnaire: a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2016; 149: 631-638.

32. Hamilton GS, Joosten SA. Obstructive sleep apnoea and obesity. Aust Fam Physician 2017; 46: 460-463.

33. Maayan L, Correll CU. Weight gain and metabolic risks associated with antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2011; 21: 517-535.

34. Stigler KA, Potenza MN, Posey DJ. Weight gain associated with atypical antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: prevalence, clinical relevance, and management. Pediatr Drugs 2004; 6: 33-44.

35. Ringen PA, Faerden A, Antonsen B. Cardiometabolic risk factors, physical activity and psychiatric status in patients in long-term psychiatric inpatient departments. Nordic J Psychiatr 2018; 72: 296-302.

36. Rüther T, Bobes J, De Hert M. EPA guidance on tobacco dependence and strategies for smoking cessation in people with mental illness. Eur Psychiatry 2014; 29: 65-82.

37. Aschbrenner KA, Brunette MF, McElvery R. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness enrolled in a fitness intervention. J Nerv Ment Dis 2015; 203: 473-476.

38. Kalkhoran S, Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA, Fung V, Baggett TP. Cigarette smoking and quitting-related factors among US adult health center patients with serious mental illness. J Gen Intern Med 2019; 34: 986-991.

39. Lawn S, Campion J. Achieving smoke-free mental health services: lessons from the past decade of implementation research. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013; 10: 4224-4244.

40. Watkins A, Gould P, Fibbins H. Tobacco Treatment Resource: an intervention framework for people on psychotropic medication. Sydney: Mindgardens Neuroscience Network; 2024. Available online at: https://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/entities/publication/dc326c0a-5c9f-4fd5-9e3f-f38a5cbb89f4 (accessed May 2025).

41. Taylor GM, Itani T, Thomas KH. Prescribing prevalence, effectiveness, and mental health safety of smoking cessation medicines in patients with mental disorders. Nicotine Tob Res 2020; 22: 48-57.

42. NSW Government. Physical health care for people living with mental health issues. Sydney: NSW Government; 2021. Available online at: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/mentalhealth/professionals/physical-health-care/Pages/default.aspx (accessed May 2025).

43. Department of Health, Australian Government. The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan. Canberra: Australian Government; 2017. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/the-fifth-national-mental-health-and-suicide-prevention-plan-2017.pdf (accessed May 2025).

44. National Mental Health Commission. Equally Well consensus statement: improving the physical health and wellbeing of people living with mental illness in Australia. Sydney: Australian Government; 2016. Available online at: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/lived-experience/contributing-lives%2C-thriving-communities/equally-well (accessed May 2025).

45. Thornicraft G. Physical health disparities and mental illness: the scandal of premature mortality. Br J Psychiatry 2011; 199: 441-442.

46. Morgan M, Hopwood MJ, Dunbar JA. Shared guidelines and protocols to achieve better health outcomes for people living with serious mental illness. MJA 2022; 217(Suppl 7): S34-S35.