Making the time count: optimising referrals from general practice for mental health treatment

Some important aspects for GPs to consider when making mental health referrals include engaging the patient in preparing for the consultation, clarifying the expected outcomes and ensuring these expectations are realistic, providing short-term strategies and navigating treatment and other management options.

- GPs can use the waiting time for a mental health specialist consultation to encourage patients to be proactive about the referral.

- Introducing coping strategies can be useful for patients during the waiting period.

- It is important to watch out for indicators of a different issue than initially determined (e.g. domestic violence, eating disorder) and indicators of increased urgency (e.g. suicidality, harm to others).

- There are several useful resources and strategies that GPs can access for assistance.

- A prepared patient will get more out of the mental health referral.

Australia has an excellent healthcare system in place for emergency situations. However, there may be prolonged waiting times before patients can access outpatient specialist care when the need is considered less acute. Increasing chronicity and complexity of presentation has increased the burden to all aspects of the healthcare system and has had an impact on when and what care can be delivered. This can be challenging for clinicians and the families supporting a person in distress.

This article is intended as a practical guide for GPs to support patients between referral and consultation for mental health specialist input. The references included in this article are linked to useful tools and resources. Although these are generalisable to any specialisation referral process, the focus is on general practice, where most referral processes are initiated and where longstanding relationships enable ongoing contact during the time awaiting review. The diagnostic and assessment processes are beyond the scope of this article, which discusses:

- the importance of clarifying the clinical outcome(s) GPs and their patients wish to achieve from the referral

- information that may be helpful to gather before the consultation

- how to ensure patients’ safety while awaiting specialist consultation

- how family members and other support systems may be involved.

The diagnostic and assessment processes are beyond the scope of this article.

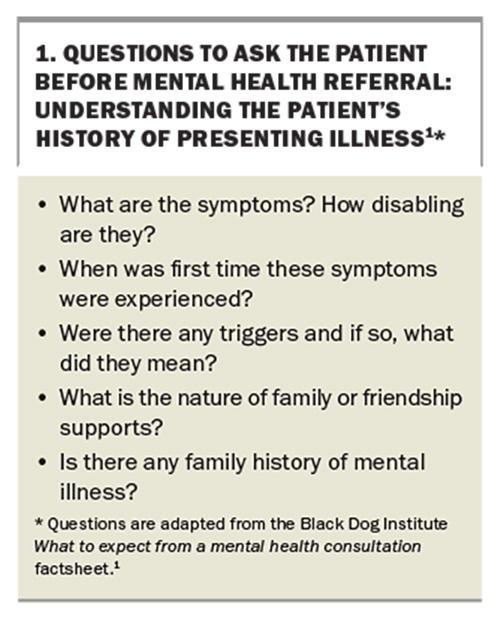

Writing a referral letter

When writing a referral letter, it is useful to clarify whether the GP and patient have similar goals and expectations. These may be influenced by previous experience, access to services and the patient’s health literacy. Box 1 lists some questions to ask the patient when referring them to a mental health specialist.1 The questions pertain to depression and anxiety but can be generalised to other disorders. The GP can ask the patient to answer the appropriate questions either in person or at home. The patient’s responses can be used to guide the details included in the referral letter and may also help redirect management while awaiting the specialist appointment. Patients may find the act of considering these questions therapeutic or useful. Patients with cognitive impairment from illness or traumatic recall may need support to answer these questions.

Arriving at a shared view of clear and realistic goals for the referral

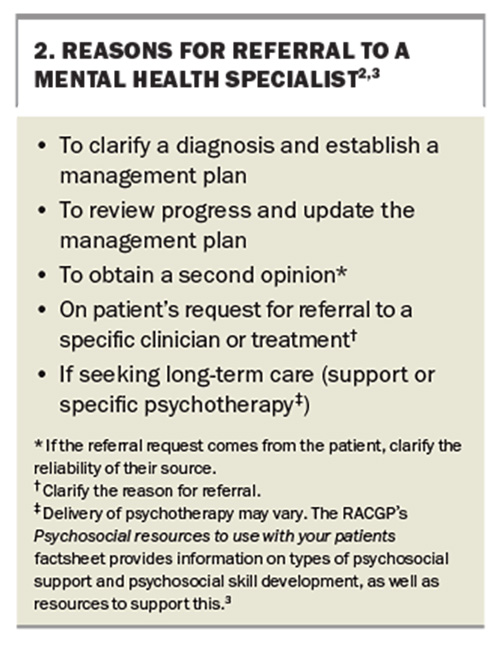

The reasons for referral to a mental health specialist can vary (Box 2).2,3 For patients referred for a second opinion, if the referral request comes from the patient, it is worth clarifying the reliability of their source (e.g. word of mouth, Internet search), which may clarify their expectations and health literacy. Other important issues are availability and access to the desired service.

Clarifying the reason for referral may be helpful for patients requesting a specific clinician or treatment. The Identifying your priorities factsheet from the Black Dog Institute provides plain language reflections to elicit referral intent or may provide ideas for brief intervention.2

Psychotherapy is delivered by trained clinicians, including social workers, psychologists, GPs or psychiatrists. Some psychiatrists provide psychotherapy, whereas others may work with a psychotherapist to focus more on assessment and medication. A clinician may specialise in one or more specific forms of treatment, and access to funding for services may differ. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Specific Interest Group has developed the Psychosocial resources to use with your patients factsheet, which provides information on types of psychosocial support and psychosocial skill development, as well as resources to support this.3 Referrals may be to establish regular review and a long-term therapeutic relationship, or may be ‘one off’ to confirm a diagnosis, provide a second opinion, provide a medicolegal report or update a current management plan.

Using the time to gather medical information

It can be particularly helpful for the patient to gather information regarding timelines of medication or treatment use and effects. Examples of information to gather include:

- a list of medications (current and previous, if relevant)4

- an emergency plan (can be created online at: https://www. beyondblue.org.au/get-support/beyondnow-suicide-safety-planning)

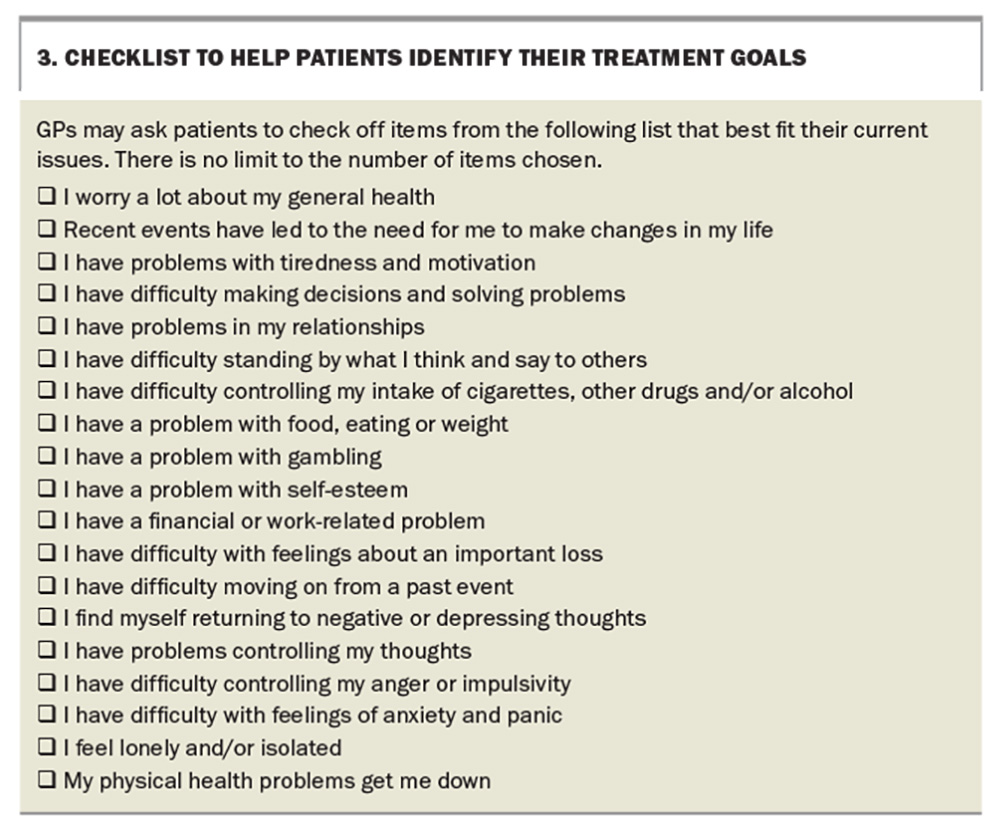

- a checklist of priorities for the patient and their family to help identify their treatment goals (Box 3)2

- relevant mental health plans, eating disorder management plans and patient consent forms

- results of any relevant clinical tests.

Triaging and referring patients to the right service

The referral pathway can depend on several factors, including:

- clarity about the desired clinical outcome of the referral

- clinician and patient engagement with the process, which is often influenced by previous experience and health literacy

- access to services.

The outcomes may become clearer after writing the referral letter, establishing clear and realistic goals and using the time to gather information.

Management while awaiting the specialist appointment

The role of medications

The role of medications depends on the context of the presentation and potential diagnosis. Many GPs are comfortable with prescribing medications. GPs who have a good relationship with the referred psychiatrist may wish to seek specific advice while the patient is awaiting the scheduled appointment. The GP Psychiatry Support Line (ph: 1800 16 17 18; https://www.gpsupport.org.au) is a nationally funded resource that connects GPs directly to psychiatrist advice.

Medications for specific mental health presentations where guidelines already exist are beyond the scope of this article. Outside of recommended guidelines, mental health-specific medications are often prescribed in response to emotional distress. However, the reason for distress or deterioration should be assessed and the decision for treatment based on this assessment. Emotional distress is not always a sign of deterioration; rather, it may reflect the patient’s response under stress or to transitional changes. Medications can ameliorate extremes of emotion but may not address why they exist in the first place.

If the purpose for referral is for diagnostic assessment, prescribing a medication that may mask the symptoms of note can mislead the assessment, making diagnosis more difficult. However, in some cases, a trial of a medication may add clarity to the diagnosis.

For any pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatment, there should be a rationale for prescribing that includes the risks and duration of treatment, the review process and when you may deprescribe treatment. The collaborative decision- making that occurs when triaging and referring patients to the right service can also be useful in pharmacological prescribing. The patient should have realistic expectations regarding the role of medications. The increasing awareness of the risks associated with prescribing benzodiazepines has increased the off-label prescribing of antipsychotics such as quetiapine.5

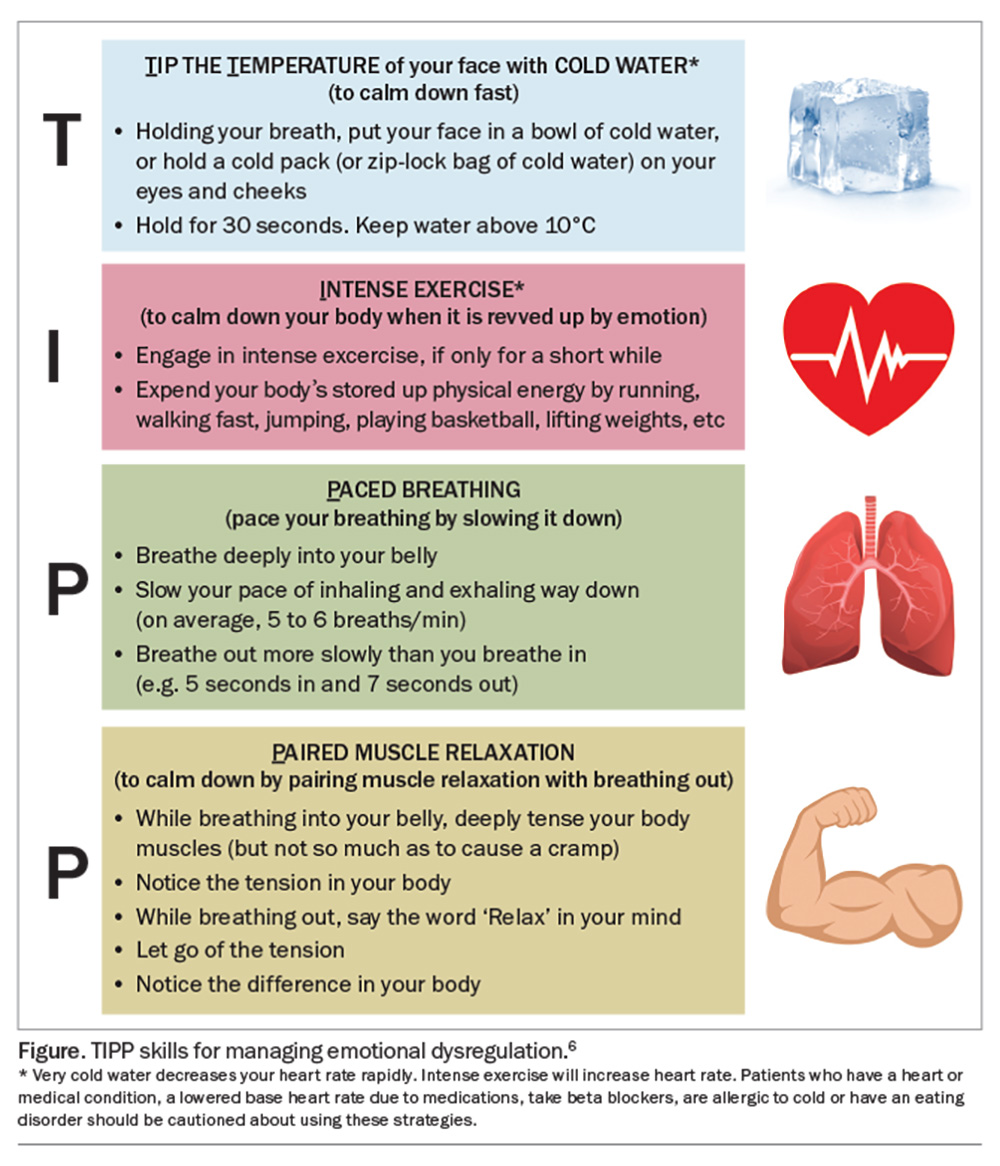

Aside from addressing the cause of distress (which may require treatment), the suggested management for emotional distress may be helpful. The TIPP skills, originally developed for dialectical behaviour therapy skills training to manage severe emotional dysregulation, can be useful for any individuals who are acutely distressed (Figure).6

Utilising coping strategies

Introducing coping strategies can be useful for someone waiting for a specialist appointment and can also provide further information on the patient’s level of interest and motivation to improve their mental health. Any move towards improving self-care can foster patient confidence, and there are benefits to learning how to set simple goals for improving diet or exercise habits and learning to use a slow breathing technique. The RACGP Psychosocial resources to use with your patients factsheet provides information on types of psychosocial support and psychosocial skill development, as well as resources to support this.3

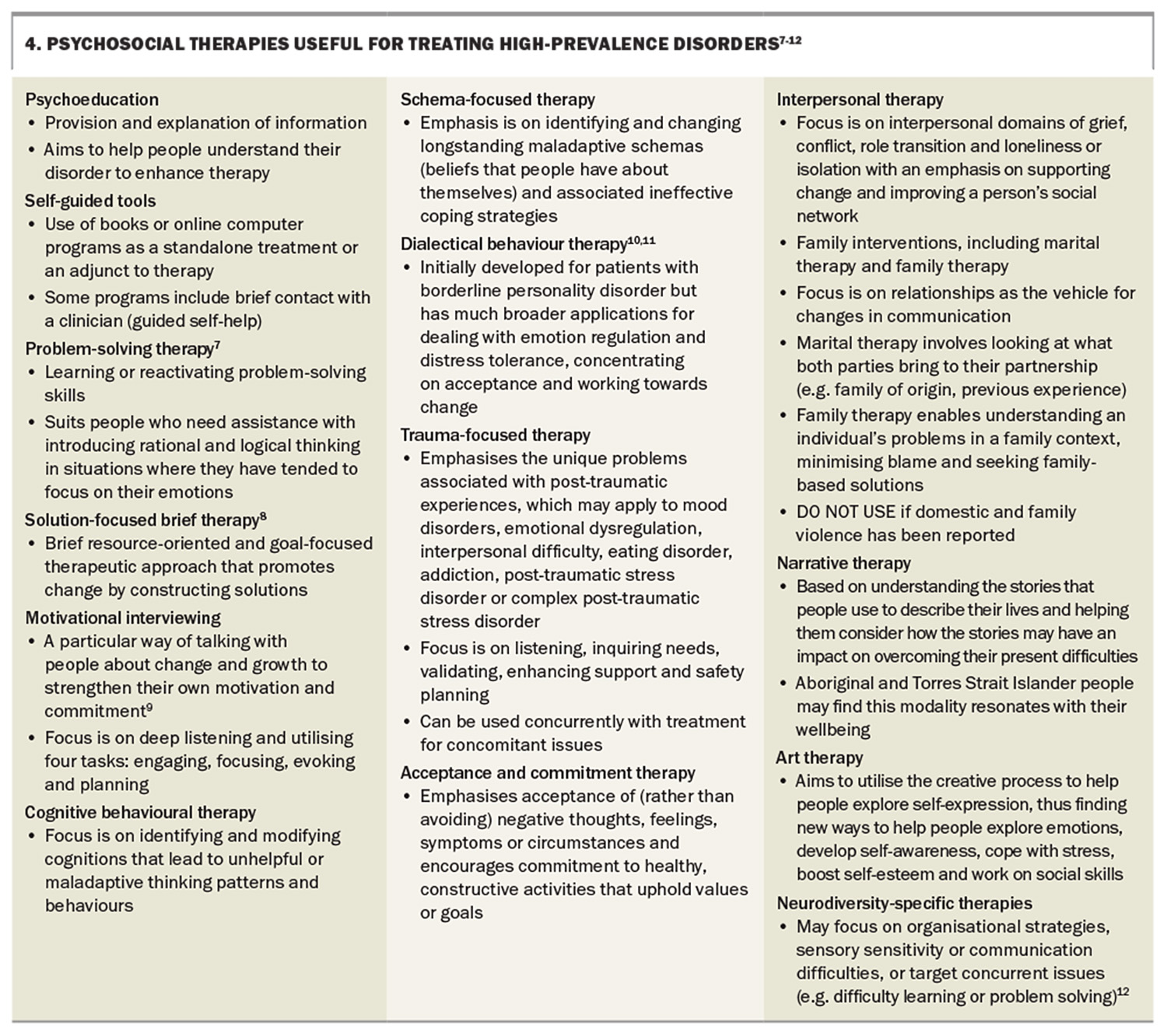

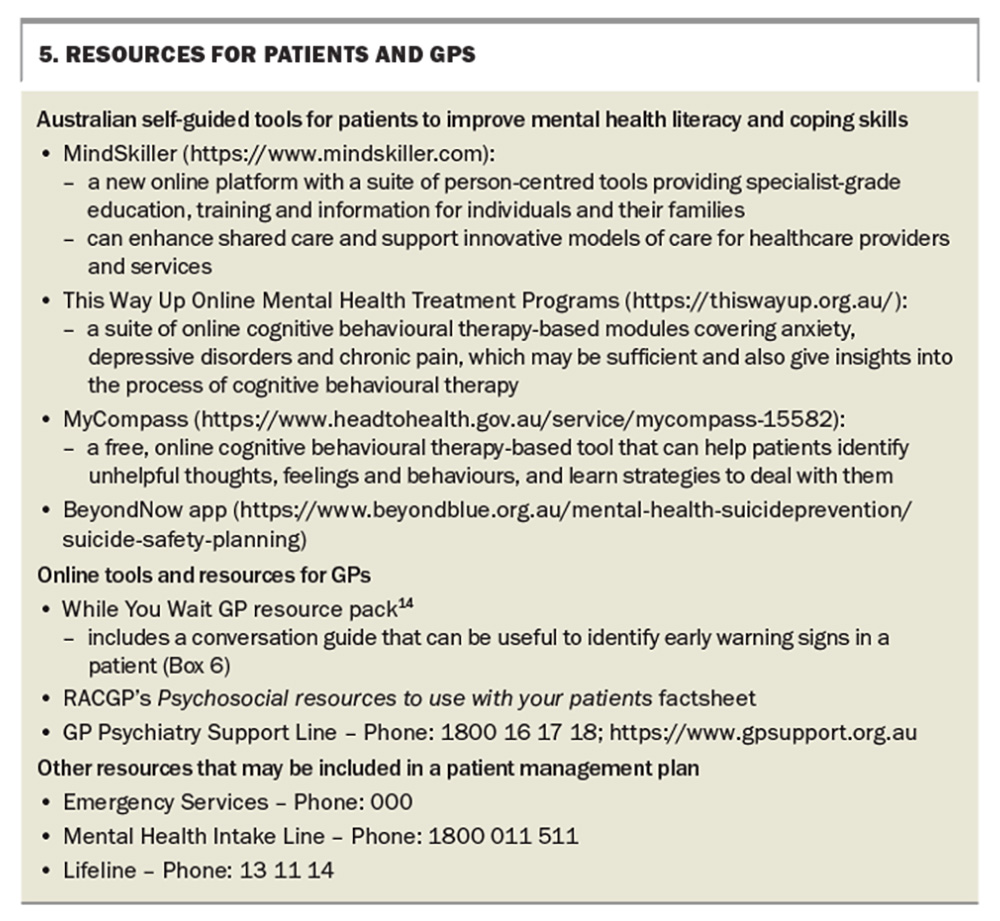

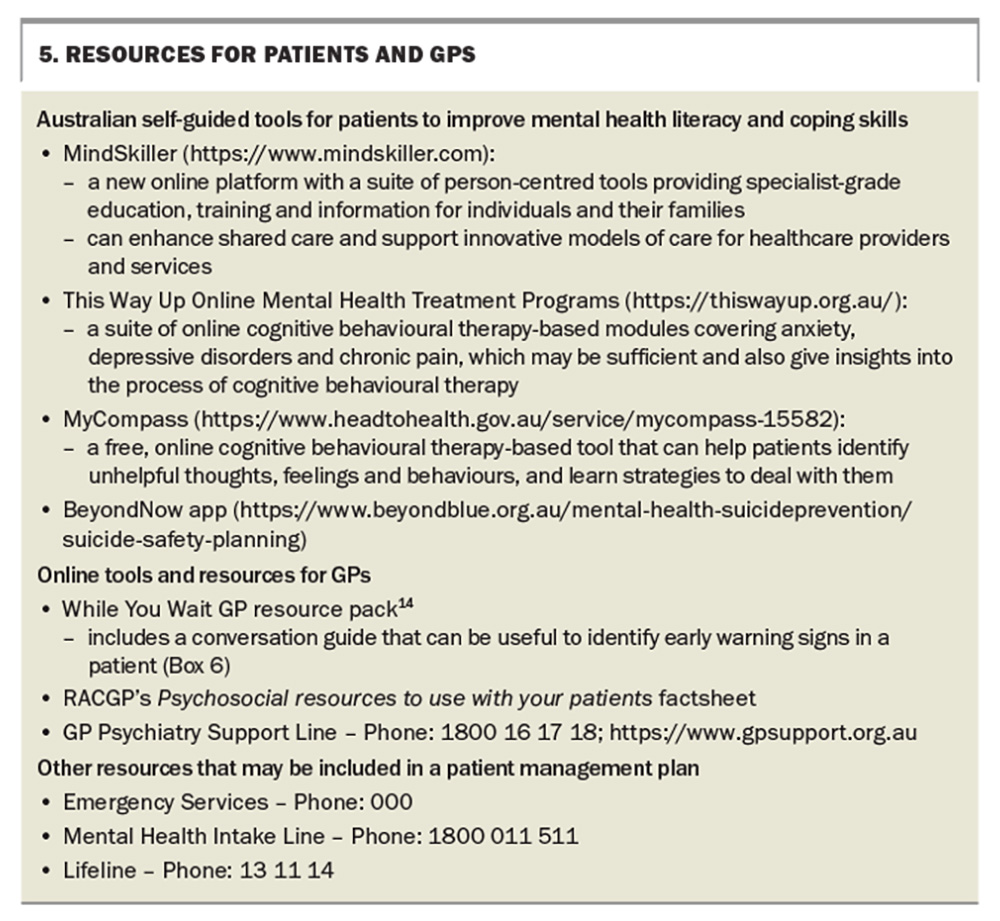

Simple psychological strategies include problem-solving (cognitive behavioural therapy-based strategies), distress tolerance (mindfulness, meditation and help-seeking) and self-reflective activities (journalling, receiving counselling and mentoring). Brief descriptions of psychosocial therapies useful for treating high-prevalence disorders (depression, anxiety personality and interpersonal issues) are included in Box 4.7-12 Box 5 lists some valuable Australian self-guided tools that may assist patients in improving their mental health literacy and coping skills.

Supporting the family and carers

Supporting the patient’s family members and carers may be just as helpful as supporting the primary patient. Family members and carers may be encouraged to:

- consider what has worked for the patient in the past

- use a self-paced online program (e.g. MindSkiller, MyCompass) to improve their own knowledge, coping skills and even train to become a mentor or peer support

- consider a psychosocial resources list (e.g. RACGP Psychosocial resources to use with your patient factsheet)3

- assist the patient with problem-solving and goal-setting13

- improve their own modifiable lifestyle factors.

Watching out for indicators of the need to change strategies

The patient may improve with mutual reflection on their goals and expectations, in combination with simple strategies, as this process can be therapeutic. However, their condition may also worsen for a variety of reasons. It may become apparent that the issue you thought the referral was for is something different (e.g. undisclosed domestic and family violence, an eating disorder, substance abuse or gambling). The patient may come to realise that the issue may be something else they have been afraid or embarrassed to disclose. Stigma may be a barrier to disclosure. Consider:

- further or ongoing psychosocial stressors (e.g. financial, housing, illness, relationship crises)

- using a psychosocial resource (e.g. RACGP Psychosocial resources to use with your patients factsheet)3

- that families may divulge information previously hidden or overlooked that may prompt psychological crisis; such revelations may be helpful and provide opportunities for recovery, but the person may require support through the process

- that diagnoses, such as evolving psychosis, significant mood disorder or underlying neurodiversity, may become more evident over time.

Increased urgency of presentation

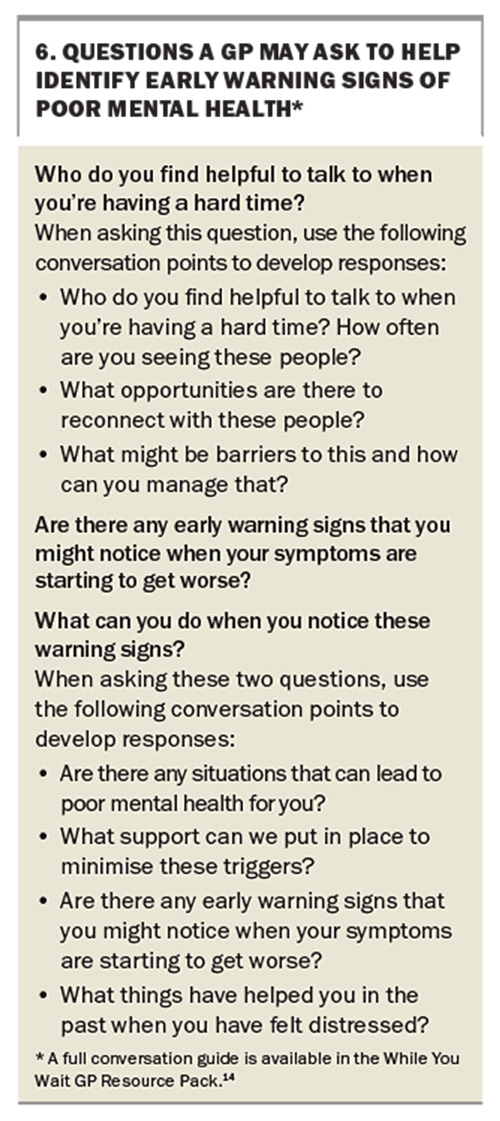

Clinicians should remain vigilant to presentations that indicate an increased urgency, and numerous tool are available to assist with this. Indicators of increased urgency include states of acute agitation, suicidality, delirium, increased substance use or impulsive behaviour, threats to or assaults on others and worsening mood with suicidal ideation or self-harm. Initiating a conversation with the patient can be useful to identify early warning signs of poor or declining mental health. Questions that may be asked to help identify such patients are presented in Box 6.14

The Beyond Now Safety Planning Intervention was designed to provide some structure to guide safety planning. The tool has been shown to be useful, highlighting the need to better promote safety planning as a beneficial intervention.15 It seeks to identify actions in a series of steps reflected in the BeyondNow app (https://www.beyondblue.org.au/mental-health/suicide-prevention/suicide-safety-planning), including:

- recognising warning signs of suicide risk

- creating a safe environment

- identifying reasons to live

- providing internal coping strategies

- providing socialisation strategies for distraction and support

- encouraging contact with trusted contacts for assisting with a crisis

- encouraging contact with professional contacts for assisting with a crisis.

It is important to listen to the concerns of family members and other carers and work with them and supporting clinicians to access local mental health services, if required. The Beyond Now intervention can help with this process, by providing a sense of whether the patient needs more urgent help. GPs should not feel alone in addressing concerns about, and seeking further assistance for, patients presenting with indicators of increased urgency, and it is reasonable to reach out for support urgently if the situation changes or becomes more urgent. These tools may assist with communicating the need for urgency if required. Resources that can be included in a patient management plan using the BeyondNow app and are also included in the While You Wait GP resource pack are listed in Box 5.

Conclusion

This article provides a reflection on the process and expectations for mental health referral to help enhance the experience for clinicians, patients and family members by the time they arrive at the specialist consultation. Resources for safety planning and psychological and psychosocial skill development are also provided. Although these principles are intended for mental health referrals, they are also appropriate for cases of complex chronic conditions. MT

COMPETING INTEREST: At the time of commencing the writing of this article, Dr Su and Professor Wilhelm were on the Advisory Committee and Mental Health and Suicide Committee at Central and Eastern Sydney Primary Health Networks (CESPHN); and on the Advisory Committee during the development of the While you Wait resource. Dr Su also coordinated the RACGP Psychosocial Resource as Chair of the RACGP specific interest group on abuse and violence in families.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: We thank Associate Professor Gary Galambos (founder and developer of MindSkiller) for comments and suggestions regarding the article.

References

1. Black Dog Institute. What to expect from a mental health consultation. Sydney: Black Dog Institute; 2022. Available online at: https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/What-to-expect-from-a-mental-health-consultation-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed June 2024).

2. Black Dog Institute. Identifying your priorities. Sydney: Black Dog Institute; 2020. Available online at: https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/14-prioritiesidentifyingyourprioritiessheet.pdf (accessed June 2024).

3. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Psychosocial resources to use with your patients. Melbourne: RACGP; 2023. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/Faculties/SI/Psychosocial-resources-AVF-SIG.pdf (accessed June 2024).

4. Black Dog Institute. Treatment chart instructions. Sydney: Black Dog Institute; 2020. Available online at: https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/21-treatment-chart.pdf (accessed June 2024).

5. Brett J. Concerns about quetiapine. Aust Prescr 2015; 38: 188-190.

6. Distress Tolerance Handout 6. In: Linehan MM. DBT Skills Training Handouts and Worksheets, Second Edition.

7. Pearce D. Problem solving therapy - use and effectiveness in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 2012; 41: 676-679

8. Zhang A, Franklin C, Currin-McCulloch J, Park S, Kim J. The effectiveness of strength-based, solution-focused brief therapy in medical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Behav Med 2018; 41: 139-151.

9. Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change and grow. 4th ed. New York: Guildford Press; 2023.

10. Chanen A, Thompson K. Prescribing and borderline personality disorder. Aust Prescr 2016; 39: 49- 53.

11. Linehan MM. Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

12. ADHD Guideline Development Group. Australian evidence-based clinical practice guideline for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Melbourne: Australian ADHD Professionals Association; 2022. Available online at: https://adhdguideline.aadpa.com.au/ (accessed June 2024).

13. Blashki G, Morgan H, Hickie IB, Sumich H, Davenport TA. Structured problem solving in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 2003; 32: 836-842.

14. Central and Eastern Sydney Primary Health Network (CESPHN). While You Wait: Conversation Guide for GPs. Sydney: CESPHN; 2022. Available online at: https://cesphn.org.au/general-practice/help-my-patients-with/mental-health/mental-health-services-funded-by-cesphn/youth-enhanced-services/29-health-services/mental-health#WYW (accessed June 2024).

15. Rainbow C, Tatnell R, Blashki G, Melvin GA. Safety plan use and suicide-related coping in a sample of Australian online help-seekers. J Affect Disord 2024; 356: 492-498.