Cardiac tachyarrhythmias: a primary care approach

Cardiac arrhythmias are a common presentation in primary care and range from benign to potentially life-threatening. A meticulous and systematic approach will enable GPs to optimally manage patients with cardiac arrhythmias, in particular to establish a diagnosis based on the ECG findings and initiate immediate and long-term management strategies to minimise symptoms and sequelae of their condition.

- Cardiac tachyarrhythmias are common and may be benign or occasionally life-threatening.

- Presenting symptoms are usually palpitations but may include syncope.

- The crucial step is to establish an ECG diagnosis of the arrhythmia.

- Technological advances have amplified the options available for diagnosing heart rhythm disorders.

- Wearable consumer-purchased ECG technologies (e.g. smart watches) are helpful but present novel challenges.

- GPs should choose the most appropriate rhythm monitoring device to improve diagnostic yield.

- A co-ordinated and shared management approach will enable comprehensive care for the patient.

- Catheter ablation is appropriate for patients with recurrent tachyarrhythmias who either choose not to receive pharmacological therapy or fail pharmacological treatment.

GPs frequently encounter patients with cardiac tachyarrhythmias in routine practice, with palpitations estimated to account for 16% of primary care presentations.1 Palpitations are also the second most common presentation to cardiologists after chest pain.1 Cardiac arrhythmias can range from benign (premature atrial complex [PAC]) to potentially life-threatening (ventricular tachycardia). Effective diagnosis and management require a detailed, systematic approach. Traditional investigations include an ECG and 24-hour Holter monitor.

Significant technological advances in recent years have resulted in an explosion of direct-to-consumer digital devices capable of collecting comprehensive, long-term cardiac rhythm data. Despite the potential benefits, significant concerns exist regarding the risk of data overload, overconsumption of healthcare, higher rates of symptom monitoring, preoccupation and anxiety among wearable users.2-4

Although tachyarrhythmias remain the primary focus of this article, bradyarrhythmias may also be diagnosed in a significant number of patients presenting with cardiac arrhythmia symptoms. Bradyarrhythmias, diagnosed based on heart rate (<55 beats per minute) and ECG appearance, include conditions such as sinus bradycardia, slowly conducted atrial fibrillation (AF), and second and third-degree atrioventricular block. These conditions are often associated with changes in the QRS morphology (e.g. left and right bundle branch block), PR and QT interval prolongation. Of note, bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias may coexist in the same patient, such as a patient with sinus bradycardia and episodes of rapidly conducted AF. Additionally, side effects of pharmacological agents used to treat tachyarrhythmias include bradyarrhythmias.

This article presents a simplified guideline to help GPs choose the optimal device for diagnosing arrhythmias. It summarises the most encountered cardiac tachyarrhythmia in primary healthcare and outlines a broad overview of the diagnostic workup and management strategies. It also outlines when to refer patients to a cardiologist or electrophysiologist to ensure optimal outcomes. Bradyarrhythmias are not discussed in detail.

Presentation

Patients with cardiac arrhythmias may present with symptoms, including:

- palpitations: patients may describe ectopic beats (or missed beats), a strong beat or fast beats. It is useful to ask the patient what they mean by the term palpitations and ask them to describe or tap out an arrhythmia that suggests a diagnosis (e.g. ectopic beats)

- breathlessness

- fatigue

- presyncope or syncope

- chest pain

- cardiac arrest

- stroke.

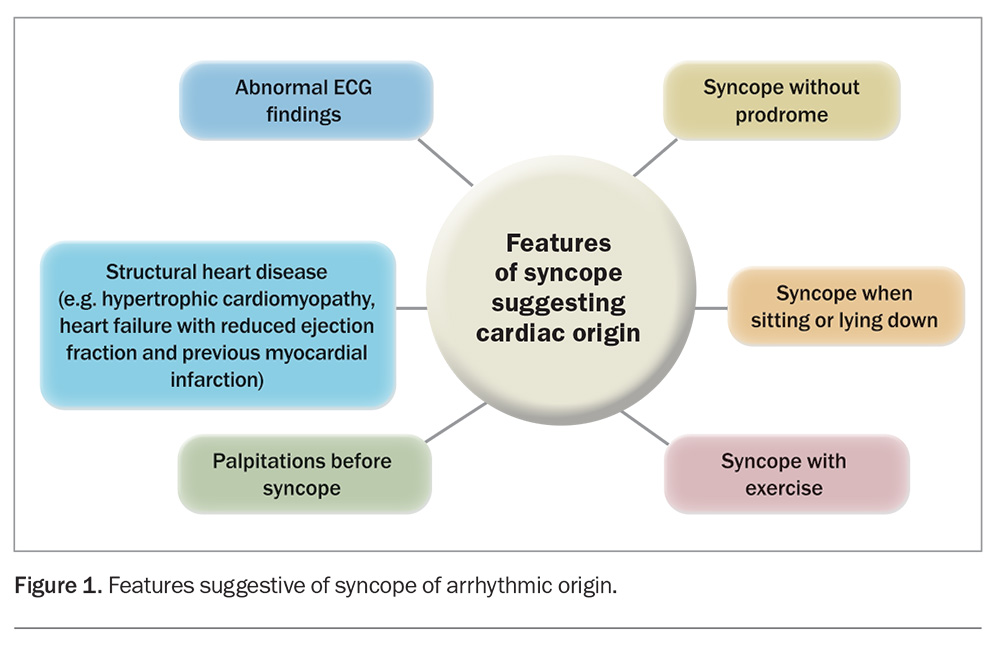

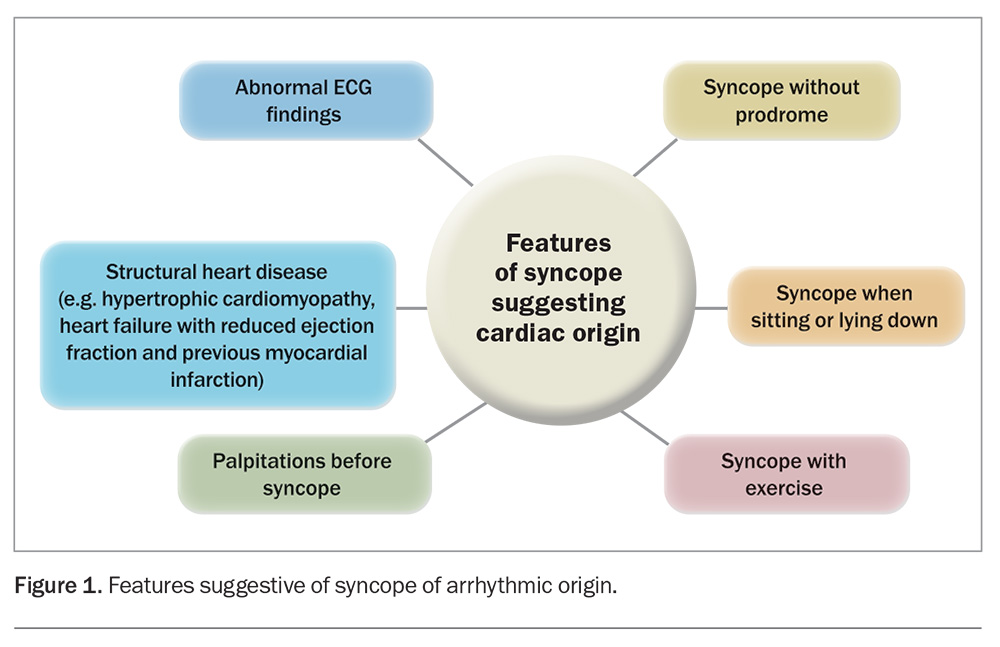

Sometimes, a patient may be completely asymptomatic, and an arrhythmia may be discovered incidentally while undergoing a routine medical check or an ECG for an unrelated reason (e.g. under anaesthesia, during a sleep study or during an EEG). Wearable technology can also alert the patient about a heart rate or rhythm that is concerning, including during sleep or exercise. Features increasing the probability of the syncope being of cardiac aetiology are detailed in Figure 1.

AF is associated with obesity, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnoea and prior cardiac diagnosis. Older age increases the risk of serious arrhythmia. The presence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia and positive family history of cardiac disease) increases the likelihood that coronary artery disease may be an aetiologic factor in ventricular arrhythmia. Occasionally, ventricular arrhythmias (e.g. premature ventricular complexes [PVCs], nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, sustained ventricular tachycardia) may be the first presentation of serious cardiovascular disease.

Examination

Physical examination remains an integral component of the evaluation and aims to identify the heart rate and regularity, hypertension, valvular heart disease, heart failure or vascular disease. Thyroid disease may be identified; however, a normal examination finding does not exclude a sinister arrhythmia as the cause of the presentation.5

Investigations

Although the patient’s history and physical examination may increase the probability of a particular arrhythmia, the ultimate diagnosis requires the arrhythmia to be documented with an ECG or a monitor.

Electrocardiography

Every patient with a suspected arrhythmia should have a standard 12-lead ECG, which can establish not only the diagnosis but may also provide valuable information regarding structural abnormalities in the heart. An abnormal ECG increases the likelihood of an arrhythmia.5

Ambulatory monitoring

Ambulatory monitoring has significantly higher sensitivity for detecting spontaneous cardiac arrhythmias. A variety of tools with different durations of monitoring are available. These tools are invaluable for accurate diagnosis, quantification and risk stratification, as well as prognostication.

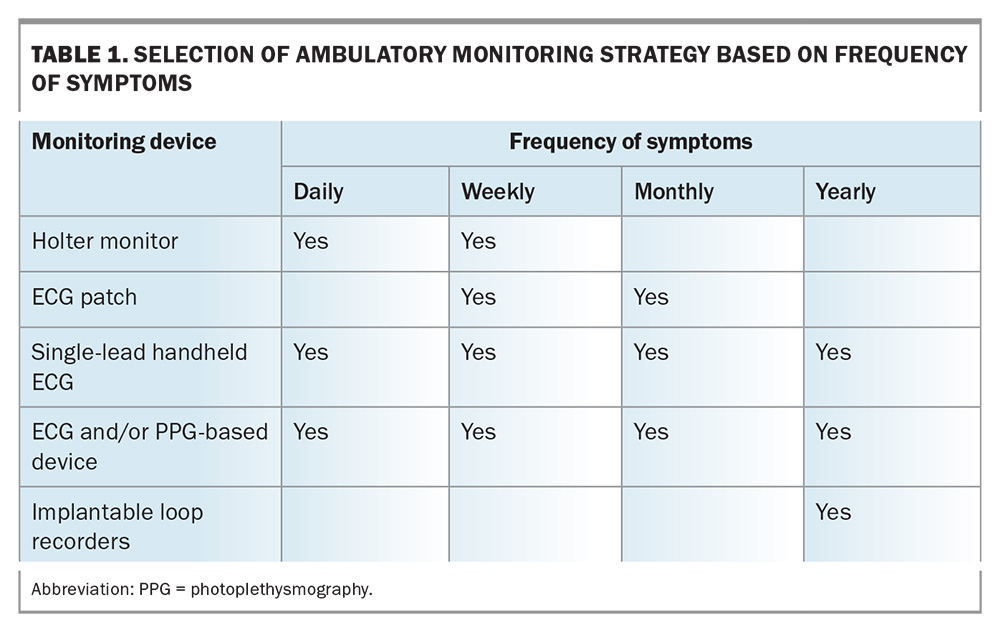

Selection of a monitoring device should be customised according to the patient’s specific needs, which include the frequency and duration of symptoms, the anticipated duration of monitoring, the available local infrastructure and the patient’s digital literacy. An overview of how to choose the optimal monitoring device based on the patient’s frequency of symptoms is provided in Table 1.

Digital devices for diagnosing and monitoring arrhythmia can be classified into two main categories based on the technology they use. These are ECG-based devices and nonECG-based devices, which are outlined in more detail below. Regardless of the type of device used, clinicians must review and interpret the recordings.

The recent advances in wearable technology and the companies adopting direct-to-consumer marketing strategies promising medical grade accuracy have resulted in a significant gap in evidence on how best to incorporate this immense data into clinical practice.

ECG-based devices

ECG-based devices include the following.

- Holter monitors: these are a common first-line investigation. Holter monitors are usually worn for 24 hours but can be recorded for up to seven days. The yield of a 24-hour monitor is proportional to the frequency of the symptoms.

- Handheld electrocardiograms (e.g. AliveCor KardiaMobile): there are multiple devices in the market allowing the patient to record an ECG signal similar to that of lead I of a standard 12-lead ECG. These devices are primarily for AF detection and have been validated in that context.6 They can also record ectopic beats and supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

- Electrocardiogram patches (e.g. Heartbug): these have many advantages, such as being low-profile, water-resistant, wireless and easy to use, resulting in improved patient adherence.7 Patches can be worn for up to one month, can diagnose arrhythmias with high accuracy and have higher diagnostic yields than traditional 24-hour Holter monitors. They have also been validated for AF detection.7-8

- Smartwatch electrocardiograms (e.g. Apple watch, Samsung Galaxy Watch): these are now widely used for health monitoring, offering features such as a single-lead, 30-second ECG recording through built-in electrodes. Users can view ECGs on the watch, store them in a mobile app and send PDFs to healthcare providers. These devices can detect AF using algorithms, and a recent meta-analysis concluded that their accuracy is on par with traditional AF monitoring.9 Despite earlier battery life issues, new hybrid models provide longer use.10

- Implantable loop recorders: these are small devices that are inserted subcutaneously under the chest wall. Although implantation of implantable loop recorders is an invasive approach, it is an extremely low-risk procedure and is the best option if the patient’s symptoms occur less than monthly. Loop recorders enable continuous monitoring of arrhythmias for up to three to five years. Traditional indications are syncope or cryptogenic stroke under current Medicare guidelines.

A recent article validates the accuracy of five frequently used smart devices, namely the Apple Watch 6, Kardia Mobile, Fitbit Sense, Samsung Galaxy Watch 3 and the Withings ScanWatch.11

NonECG-based devices

NonECG-based devices use alternative technologies such as photoplethysmography (PPG). PPG monitors use a light source and a detector to detect changes in blood volume on the skin surface, measured as changes in reflected light intensity, and then generate a pulse waveform.12 PPG is routinely used in clinical practice to measure oxygen saturation and pulse rate, but only recently has it been used to detect AF, both in contact (finger-over-the-camera) and contactless (facial video monitoring) settings, using a smartphone and a digital camera.13,14 Advances and miniaturisation of PPG technology have resulted in wearable rings capable of continuous heart rate monitoring (Oura ring), ECG analysis and collection (Cardio Ring), and even the ability to provide a full surface reconstruction of a 12-lead ECG (ECG recording rings, Everbeat).15 ECG-based wearables are preferred over PPG technology for establishing a diagnosis.16

Ancillary investigations

Ancillary investigations include blood tests (e.g. thyroid function tests, full blood counts and biochemistry profile) and a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). A TTE is a standard evaluation in a patient with a suspected or proven arrhythmia, and is valuable to rule out structural heart disease. It is usually normal in a patient with SVT or ectopic beats. Rarely, a patient with a serious ventricular arrhythmia may have a normal TTE.

Other investigations include stress testing, coronary calcium score, CT coronary angiography and cardiac MRI. Excluding coronary artery disease is not a routine part of the investigation of tachyarrhythmias in younger patients but may be indicated in older patients with AF or ventricular arrhythmia. Cardiac MRI is an important tool in refining the diagnosis and management of structural heart disease and ventricular arrhythmias. Access to cardiac MRI in primary care may be limited in certain areas but for some patients it is a key investigation that provides unique information and impacts decision making. Cardiac MRI is usually requested by a cardiologist.

Common arrhythmias

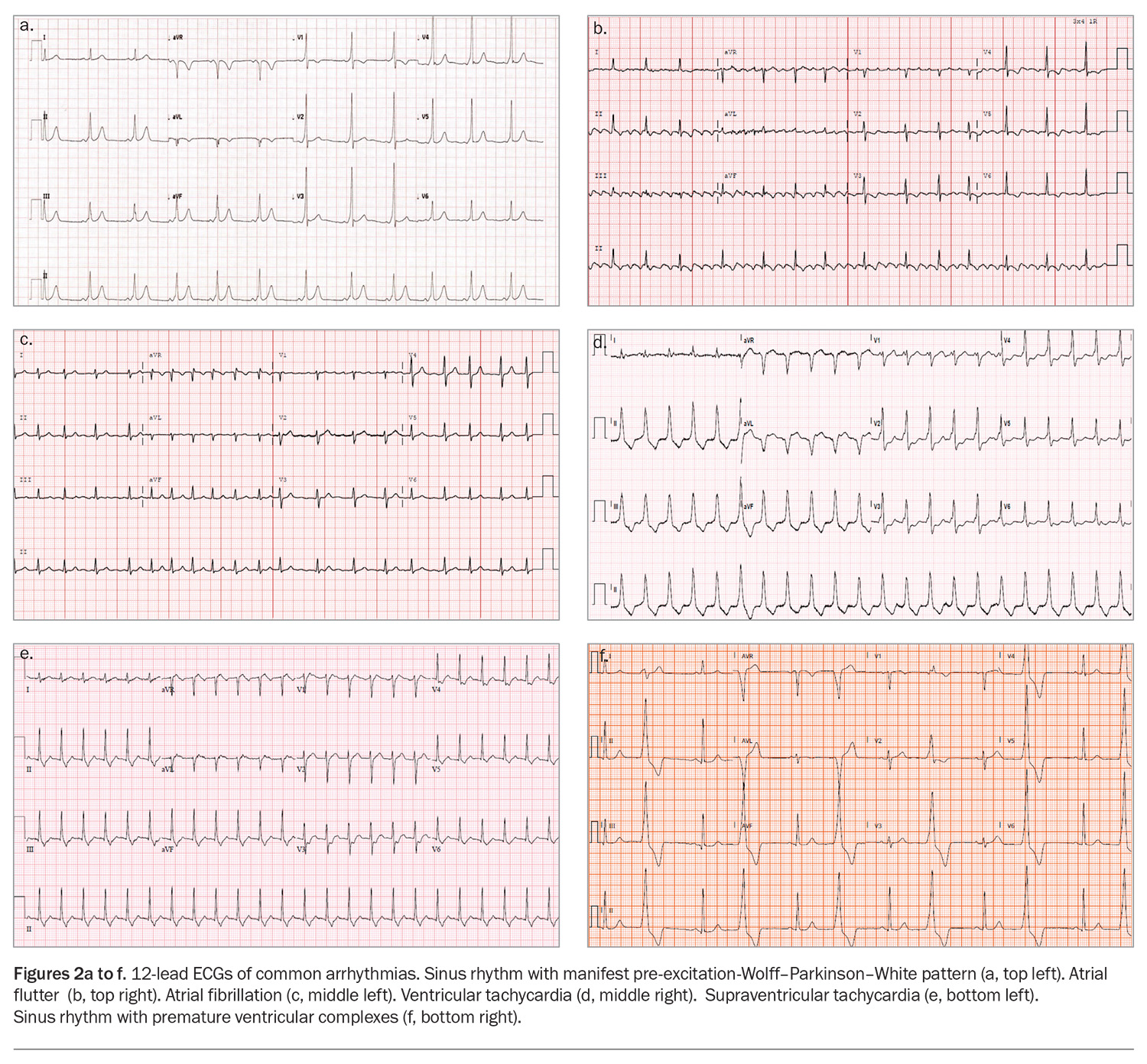

The common cardiac arrhythmias can be subdivided broadly into atrial arrhythmias and ventricular arrhythmias. Examples of 12-lead ECGs showing common arrhythmias are presented in Figures 2a to f.

Atrial arrhythmias

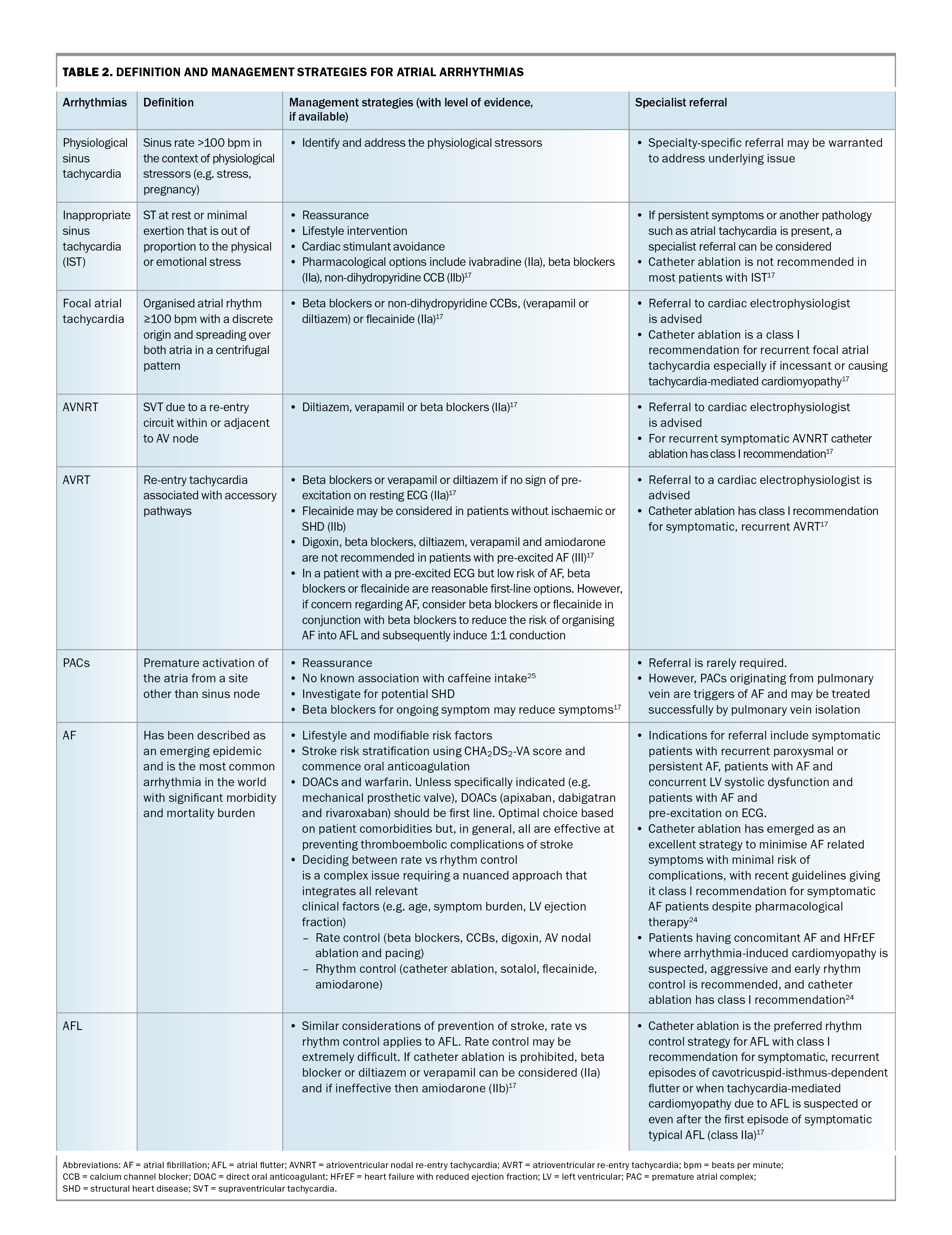

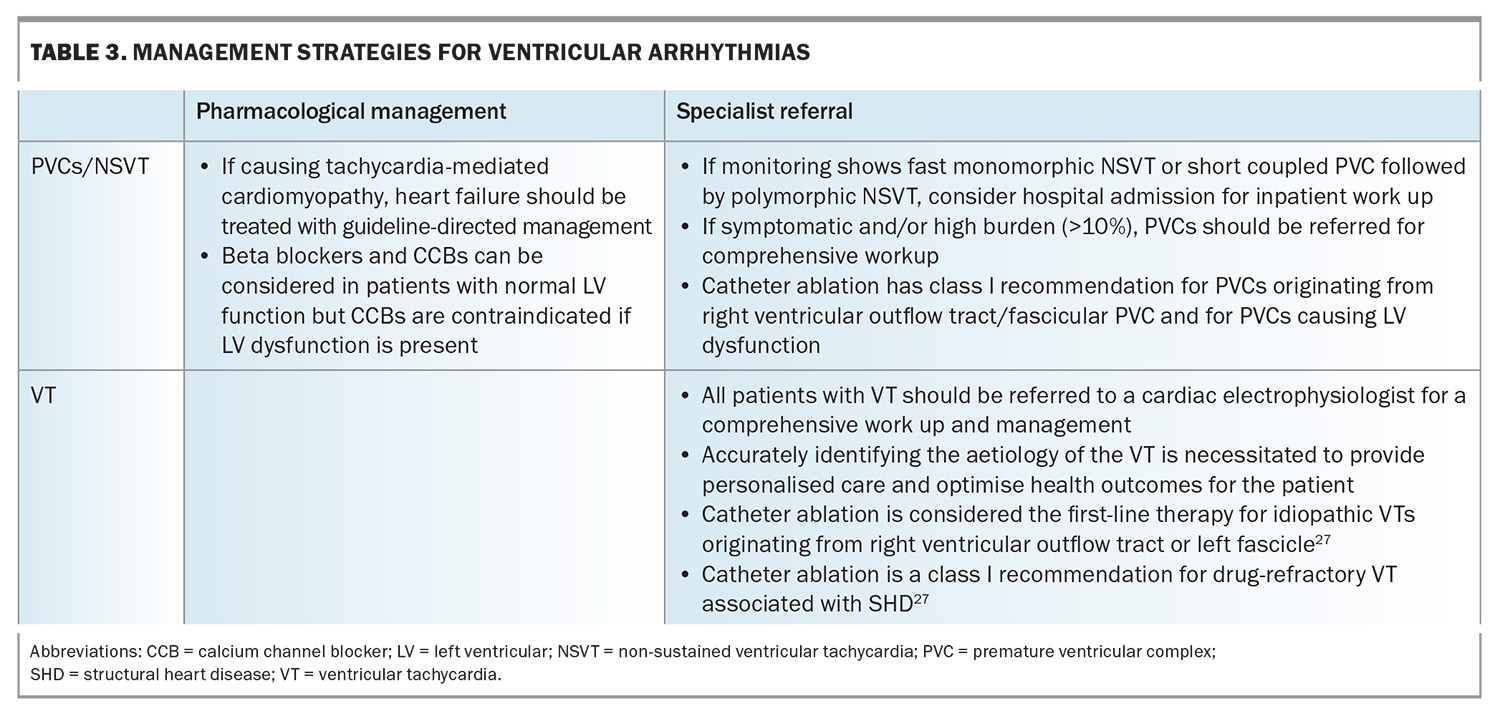

The definition and management strategies for atrial arrhythmias are shown in Table 2. Atrial arrhythmias include the those listed below.

- Inappropriate sinus tachycardia: a fast sinus rhythm (>100 beats per minute) at rest or out of proportion with stress. The underlying mechanism remains poorly understood and likely multifactorial (e.g. dysautonomia, neurohormonal dysregulation and sinus node hyperactivity).17

- PACs: usually common and benign. In rare cases, a PAC may be a trigger for sustained arrhythmia such as AF.

- AF: the most common arrhythmia worldwide, with its incidence and prevalence increasing globally across all societies.18,19

- Atrial flutter: a macro-reentrant atrial tachycardia closely related to but distinct from AF. Atrial flutter may occur in patients with congenital heart disease, prior cardiac surgery or with underlying HF or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.20

- SVT: an all-encompassing umbrella term that can be subdivided into the following:

– atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia (AVNRT), which is a re-entry tachycardia involving the AV node

– focal atrial tachycardia, which originates within the atria but outside the sinus node. Its mechanism may be one or a combination of automaticity, triggered activity or re-entry

– atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia (AVRT), which is a re-entry tachycardia involving the accessory pathway. Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome is a congenital pre-excitation syndrome involving a manifest accessory pathway resulting in pre-excitation and recurrent tachyarrhythmias and falls under the umbrella of AVRTs. The hallmark ECG features of this syndrome are a short PR interval (≤120 msec), a delta wave and a wide QRS complex (>120 msec).17

Ventricular arrhythmias

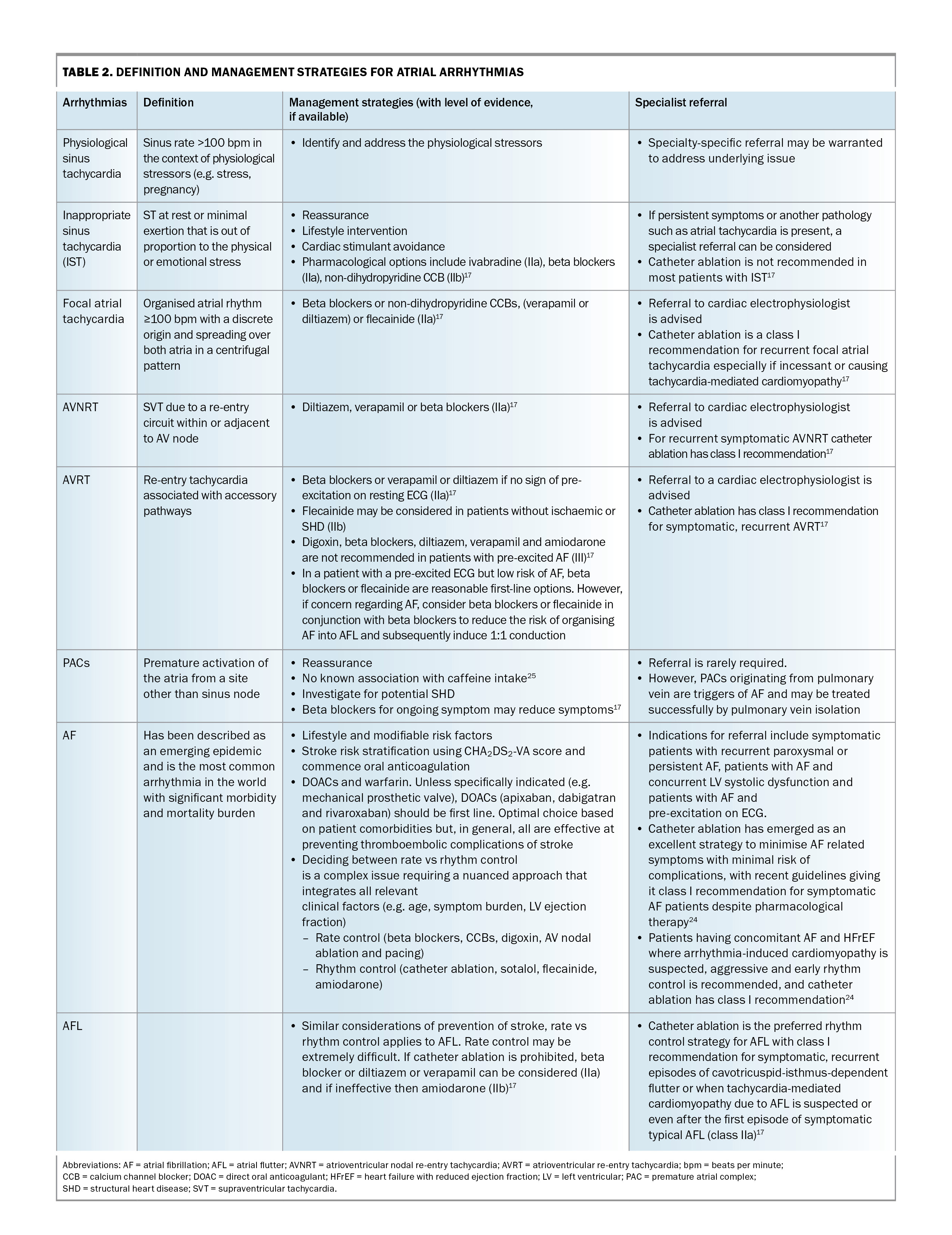

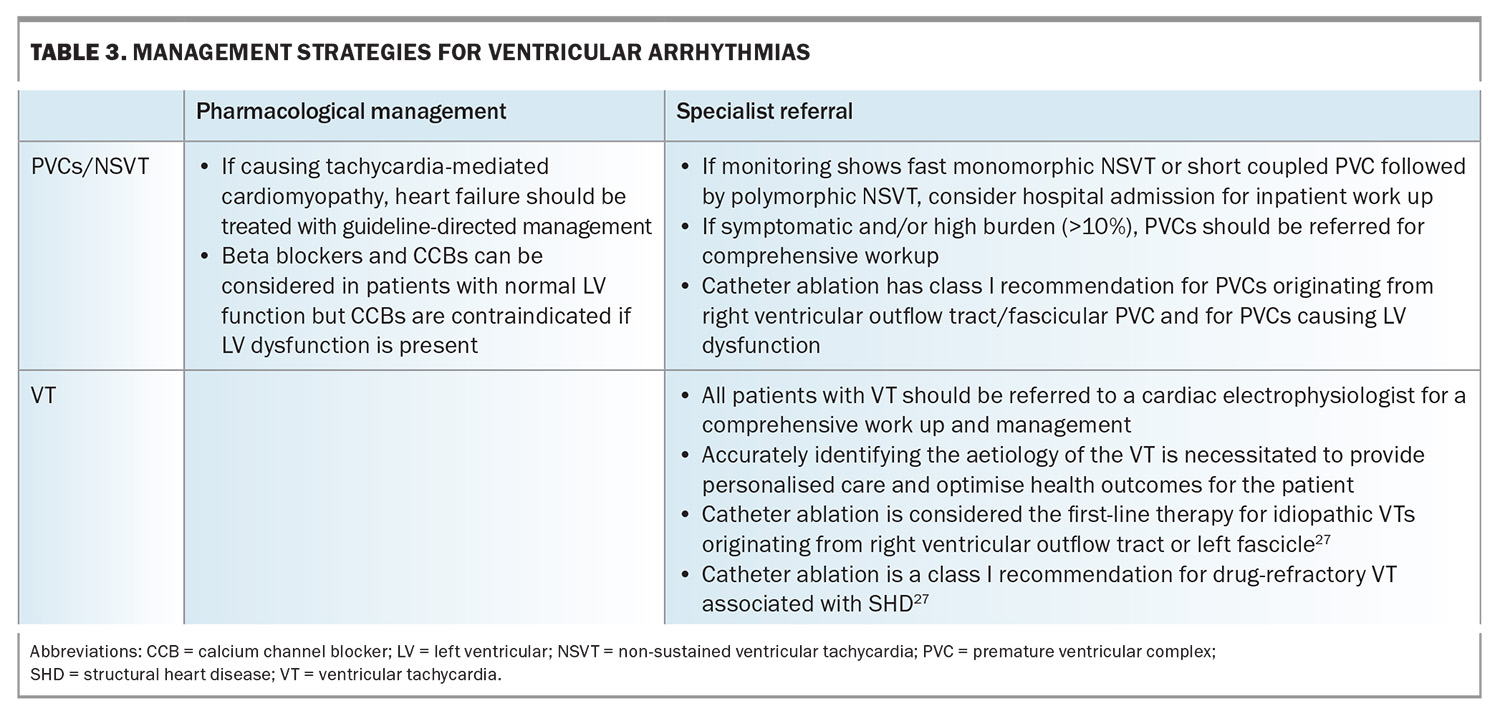

Ventricular arrhythmias may be benign or serious. They are usually stratified according to the presence or absence of structural heart disease (e.g. an abnormal TTE or cardiac MRI) and the presence or absence of syncope. Ventricular arrhythmias are a marker of sudden cardiac death risk in certain populations.21

The types of ventricular arrhythmias are listed below.

- PVCs are premature and abnormal ectopic beats of ventricular origin and are common. On 24-hour ambulatory monitoring, 80% of the apparently healthy population were found to have occasional PVCs.22,23 Although incidental findings of very low-burden PVC in asymptomatic individuals may not require further investigations, if the patient is symptomatic, ambulatory monitoring to quantify the burden of PVC, as well as a TTE looking for structural heart disease is warranted.

- Ventricular tachycardia is a wide complex tachycardia of ventricular origin and is defined as three or more consecutive beats at a rate exceeding 100 beats per minute. All patients with ventricular tachycardia should be referred to a cardiologist or electrophysiologist for comprehensive work up. Ventricular tachycardia can be broadly divided into:

– ventricular tachycardia related to structural heart disease

– idiopathic ventricular tachycardia (ventricular tachycardia in a structurally normal heart)

– nonsustained ventricular tachycardias are a run of consecutive abnormal ventricular beats for at least three beats and to 30 seconds but typically five to 15 beats. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia may be benign but requires evaluation by a cardiologist because it is a potential marker of sudden cardiac death risk.

Management strategies for ventricular arrhythmias are shown in Table 3.

Approach to management

Immediate management

Urgent rhythm control is required for patients presenting with haemodynamic compromise or decompensated heart failure in the context of an arrhythmia. If faced with such a situation in a primary care setting, the best option is hospital referral, usually via the emergency department, for inpatient management.

Long-term management

Long-term management should be personalised because symptoms and their impacts on a patient’s lifestyle, occupation, driving and daily activities vary greatly.

Lifestyle modifications

Patients should be advised on general risk factors to promote their cardiovascular health. Although the wealth of evidence highlighting the importance of addressing lifestyle factors is mostly related to AF, addressing the following factors can help a patient’s overall cardiovascular health, thereby having a beneficial effect on primary and secondary prevention of arrhythmic disease.

- Weight loss: maintenance of healthy weight or weight loss in individuals who are overweight or obese can decrease AF symptoms, burden, recurrence and progression to persistent AF.24

- Smoking cessation.

- Alcohol consumption: patients with AF should be advised to minimise or stop alcohol intake to reduce AF recurrence and burden.

- Dietary changes.

- Regular exercise.

- Sleep: GPs should consider screening for obstructive sleep apnoea and treat if indicated because of its high prevalence in the AF patient population.24

Abstinence from caffeine has not been shown to prevent AF episodes or PACs.24,25

Pharmacological therapy

The primary objective of initiating pharmacological therapy is to improve symptoms and prevent serious outcomes such as tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy secondary to AF with rapid ventricular rate. Stroke prevention is crucial for patients with AF and atrial flutter. The decision to initiate long-term treatment depends on the severity and frequency of symptoms, which must be carefully balanced with the risks of therapy.

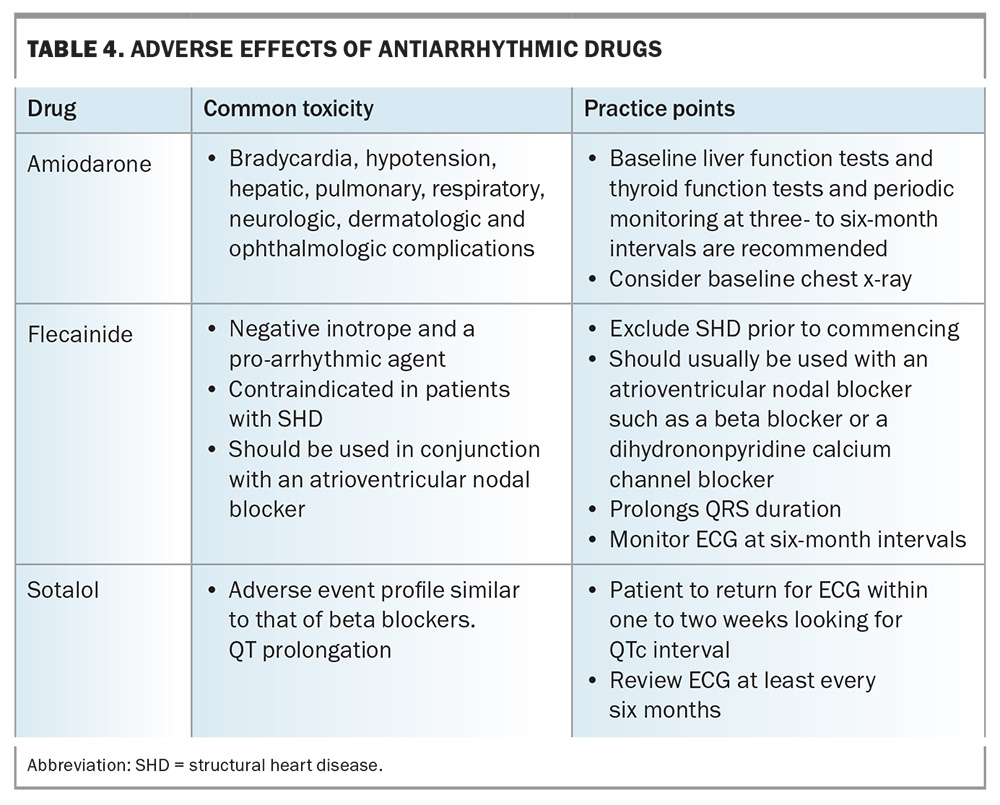

Specialist involvement is recommended when starting membrane-active antiarrhythmic drugs (e.g. sotalol, flecainide and amiodarone) because of their inherent proarrhythmic potential, which includes increased premature ventricular contractions, ventricular tachycardia, torsades de pointes, ventricular fibrillation, conduction disturbances and bradycardia. This is especially important for patients with structural heart disease, pre-excitation, conduction disturbances and heart failure. By carefully considering these factors and involving specialists if necessary, the risk associated with antiarrhythmic drugs can be minimised, leading to a safer and more effective patient outcome.

Although a detailed review of these arrhythmias is beyond the scope of this article, an overview of management options for these arrhythmias is provided in Table 2 and Table 3. Commonly used antiarrhythmic drugs and their associated side effects and monitoring strategies are listed in Table 4.

Catheter ablation

Catheter ablation, in the context of rapid innovation and technological advances, has revolutionised the treatment of arrhythmias and is a potent and definitive solution for many patients. The broad indications in which catheter ablation should be considered are as follows:

- definitive treatment for SVTs17

- AF-related symptoms (may even be considered as a first-line treatment)26

- AF and heart failure26

- atrial flutter17

- PVCs with symptoms, high-burden, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction27

- idiopathic ventricular tachycardia27

- drug-refractory ventricular tachycardia in the context of structural heart disease.27

Referral criteria

Atrial arrhythmias and PVCs are common in the general population, and GPs are adept at managing these conditions. Elective referral to a cardiac electrophysiologist should be considered for patients:

- with recurrent symptomatic atrial arrhythmias despite guideline-based initial management

- with uncertain diagnosis, prognosis or management strategy

- with wide QRS complex tachycardia

- with structural heart disease and ventricular arrhythmia

- who may benefit from a catheter ablation

- who require long-term antiarrhythmic drug therapy, especially if they have a background of structural heart disease

- with undiagnosed arrhythmia with red flags (highlighted in Figure 1)

- with PVC burden of more than 10%

- with PVCs and left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Patient education

Patients should be advised to keep an accurate log of episodes, triggers and associated symptoms. They should also be educated on the importance of medication adherence and counselled on the early identification of signs that require urgent medical attention (e.g. syncope, recurrent implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks).

Follow up

Once patients have been initiated onto a long-term medication regimen, particularly with antiarrhythmic drugs, regular follow up and monitoring are required for assessing response to treatment as well as drug adverse events. GPs remain the first point of contact to reassess the need for referral or escalation of therapies and provide ongoing reassurance, education and support.

Conclusion

Patients with cardiac arrhythmias are a common presentation in primary care. Cardiac arrhythmias comprise a diverse set of conditions, with vastly different clinical courses and prognosis. A meticulous and systematic approach will enable the GP to optimally manage the patient, the crux of which is to diagnose the arrhythmia based on ECG findings and initiate both immediate and long-term management strategies to minimise symptoms and sequelae of their condition. Timely referral to a cardiac electrophysiologist and a co-ordinated and shared management approach will enable comprehensive care for the patient. The GP remains the most crucial element in enabling shared care, providing ongoing patient education and follow up, optimising the patient’s effective long-term management and improving patient outcomes. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Raviele A, Giada F, Bergfeldt L, et al. Management of patients with palpitations: a position paper from the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2011; 13: 920-934.

2. Manninger M, Zweiker D, Svennberg E, et al. Current perspectives on wearable rhythm recordings for clinical decision-making: the wEHRAbles 2 survey. Europace 2021; 23: 1106-1113.

3. Manninger M, Kosiuk J, Zweiker D, et al. Role of wearable rhythm recordings in clinical decision making-The wEHRAbles project. Clin Cardiol 2020; 43: 1032-1039.

4. Rosman L, Lampert R, Zhuo S, et al. Wearable devices, health care use, and psychological well-being in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2024: e033750.

5. Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Khoo C, Dorian P, Choudhry NK. Does this patient with palpitations have a cardiac arrhythmia? JAMA 2009; 302: 2135-2143.

6. Wong KC, Klimis H, Lowres N, von Huben A, Marschner S, Chow CK. Diagnostic accuracy of handheld electrocardiogram devices in detecting atrial fibrillation in adults in community versus hospital settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2020; 106: 1211-1217.

7. Turakhia MP, Hoang DD, Zimetbaum P, et al. Diagnostic utility of a novel leadless arrhythmia monitoring device. Am J Cardiol 2013; 112: 520-524.

8. Barrett PM, Komatireddy R, Haaser S et al. Comparison of 24-hour Holter monitoring with 14-day novel adhesive patch electrocardiographic monitoring. Am J Med 2014; 127: 95.e11-7.

9. Elbey MA, Young D, Kanuri SH, et al. Diagnostic utility of smartwatch technology for atrial fibrillation detection - a systematic analysis. J Atr Fibrillation 2021; 13: 20200446.

10. Maille B, Wilkin M, Million M, et al. Smartwatch electrocardiogram and artificial intelligence for assessing cardiac-rhythm safety of drug therapy in the covid-19 pandemic. The QT-logs study. Int J Cardiol 2021; 331: 333-339.

11. Mannhart D, Lischer M, Knecht S, et al. Clinical validation of 5 direct-to-consumer wearable smart devices to detect atrial fibrillation: basel wearable study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2023; 9: 232-242.

12. Elgendi M. On the analysis of fingertip photoplethysmogram signals. Curr Cardiol Rev 2012; 8: 14-25.

13. Yan BP, Lai WHS, Chan CKY, et al. Contact-free screening of atrial fibrillation by a smartphone using facial pulsatile photoplethysmographic signals. J Am Heart Assoc 2018; 7.

14. Yan BP, Lai WHS, Chan CKY, et al. High-throughput, contact-free detection of atrial fibrillation from video with deep learning. JAMA Cardiol 2020; 5: 105-107.

15. Mendenhall GS, Jones MO, Pollack CV, Eoyang GP, Silber SH, Kennedy A. Precordial electrocardiographic recording and QT measurement from a novel wearable ring device. Cardiovasc Digit Health J 2024; 5: 8-14.

16. Svennberg E, Tjong F, Goette A, et al. How to use digital devices to detect and manage arrhythmias: an EHRA practical guide. Europace 2022; 24: 979-1005.

17. Brugada J, Katritsis DG, Arbelo E, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia. The Task Force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 655-720.

18. Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet 2015; 386: 154-162.

19. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;147: e93-e621.

20. Granada J, Uribe W, Chyou PH, et al. Incidence and predictors of atrial flutter in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36: 2242-2246.

21. Israel CW. Mechanisms of sudden cardiac death. Indian Heart J 2014; 66 Suppl 1: S10-S17.

22. Sobotka PA, Mayer JH, Bauernfeind RA, Kanakis C, Jr Rosen KM. Arrhythmias documented by 24-hour continuous ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in young women without apparent heart disease. Am Heart J 1981; 101: 753-759.

23. Brodsky M, Wu D, Denes P, Kanakis C, Rosen KM. Arrhythmias documented by 24 hour continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in 50 male medical students without apparent heart disease. Am J Cardiol 1977; 39: 390-395.

24. Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024; 149: e1-e156.

25. Marcus GM, Rosenthal DG, Nah G, et al. Acute effects of coffee consumption on health among ambulatory adults. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 1092-1100.

26. Tzeis S, Gerstenfeld EP, Kalman J, et al. 2024 European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2024; 26.

27. Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J 2022; 43: 3997-4126.