Gout – the pivotal role of primary care

Gout is common and increasing in prevalence in Australia and worldwide. It is associated with multiple significant comorbidities and functional disability. Despite widely available and effective pharmacotherapy, management remains suboptimal with low rates of urate-lowering therapy initiation and target uric acid levels being achieved. GPs play an important role in primary care-led management of gout and in helping to improve patient outcomes.

- Gout is a common inflammatory condition with increasing prevalence in Australia and globally.

- Diagnostic assessment modalities for gout have expanded to include ultrasonography and dual-energy CT.

- Urate-lowering therapy (ULT) is the cornerstone of management and allopurinol remains first-line therapy due to its effectiveness, tolerability and low cost.

- Lower starting doses are required for patients with moderate to severe renal impairment.

- Prophylaxis with anti-inflammatories (for three to six months) is recommended during up-titration of ULT.

- Gout management is based on a ‘treat to target’ approach focused on uric acid levels. However, suboptimal therapy is common due to lack of patient and physician education, poor adherence to therapy and infrequent uric acid monitoring.

- Patient education is paramount for adherence to ULT.

- The use of nurse- and pharmacy-led care, technology and increasing primary care awareness have been shown to improve patient outcomes.

Gout is a common inflammatory arthritis that is managed predominantly in primary care. Due to lifestyle changes, comorbidities and an ageing population, its prevalence is increasing.1 Prevalence data vary according to reporting methods but a recent review places the community prevalence between 1.5 and 6.8% in Australia.2 Both gout and hyperuricaemia are associated with numerous significant comorbidities including cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular disease.1,3 Gout can also result in functional impairment leading to work-related absenteeism and hospital inpatient admissions.

Despite the knowledge that gout is driven by hyperuricaemia and that urate-lowering therapy (ULT) is efficacious, in practice, the management of gout remains poor.1,4 Recent Australian evidence suggests that although about 50% of people with gout are prescribed ULT, a significant number of these patients discontinue therapy, less than a quarter achieve target serum urate level and most of those on ULT continue to have frequent flares, implying subtherapeutic dosing of ULT.5,6 The impact of gout on the Australian community is difficult to quantify, but most simplistically, the direct costs of hospital admissions for acute gout (which represents just a minority of patients with gout) can be estimated at $60,000,000 in 2017/18 based on 7800 admissions a year, totalling 32,000 bed days.7 Given that most admissions would be avoidable with appropriate use of ULT, there is an opportunity to greatly reduce the impact of gout on the Australian community. Health professionals in primary care play a fundamental role in managing gout. In this article, we review diagnostic pathways and management strategies, discuss barriers to optimal outcomes and attempt to address certain misconceptions.

Pathophysiology

Gout is caused by chronic deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals. Initially, hyperuricaemia arises from an imbalance between excretion of urate and hepatic production. The renal system accounts for about two-thirds of urate excretion, with the gastrointestinal tract predominantly accounting for the remainder.3 Hyperuricaemia is mostly a result of renal underexcretion as opposed to overproduction of uric acid. A small percentage of patients with hyperuricaemia go on to develop crystal deposition in joints and soft tissues, with resulting symptomatic gout.

A complex interplay between genetic and environmental risk factors is observed in the aetiopathogenesis of gout. Risk factors and associated conditions are listed in Box 1.3,8,9 Uric acid homeostasis is significantly influenced by genetic predisposition. Māoris, Pacific Islanders and indigenous Taiwanese have a considerably increased risk of developing gout.3,10 Interestingly, the Indigenous Australian population had a low prevalence of hyperuricaemia and gout in the 20th century.11 Overall prevalence is increasing in most developed nations, in line with changes in lifestyle and associated comorbidities including chronic kidney disease and diabetes.12

Diagnosis

The gold standard for the diagnosis of gout is the detection of MSU crystals in synovial fluid or tophi using polarised light microscopy. A diagnosis can be made based on clinical and radiographic findings. The clinical diagnosis of gout is based on several suggestive features as described in Box 1.8 The presence of hyperuricaemia alone should not be used to make a diagnosis of gout.

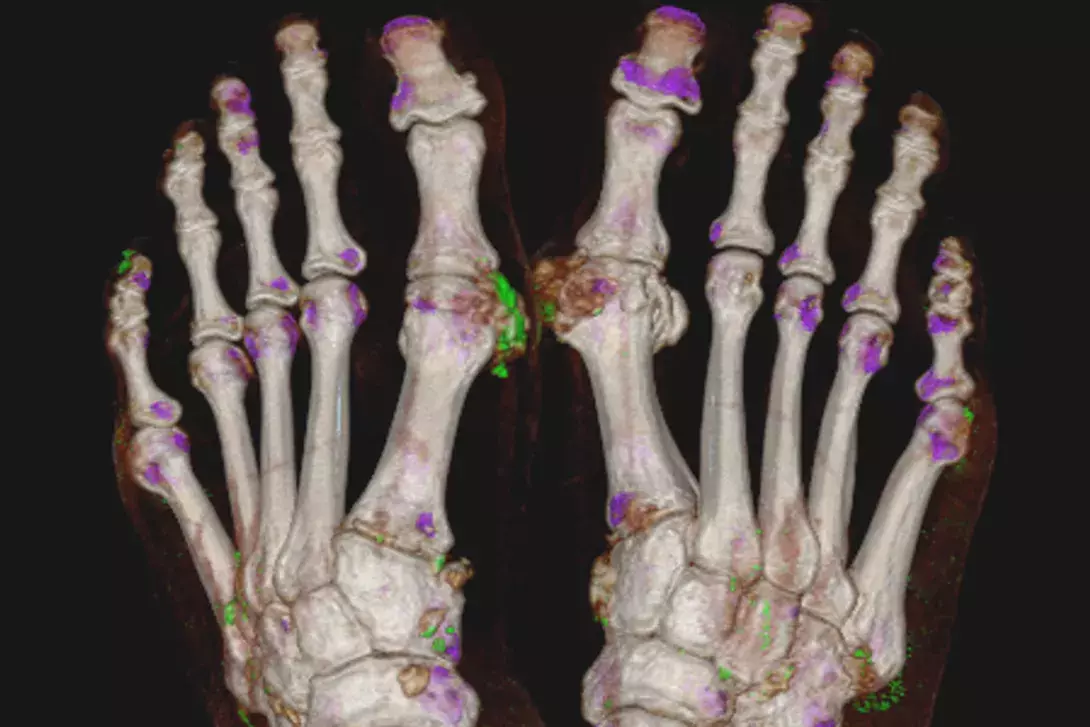

Imaging can be useful in diagnosing atypical or difficult cases. Conventional radiography can identify structural damage consistent with advanced gout (Figure 1) but is of limited use in the acute diagnostic phase. Ultrasound (US) and dual-energy CT (DECT) are useful imaging modalities, especially in atypical presentations when a clinical diagnosis of gout is uncertain and synovial fluid aspiration is not possible. Ultrasonographic evidence of urate deposition includes the double contour sign and tophi (Figure 2). The double contour sign is thought to reflect urate crystal deposition on the surface of articular cartilage. Hyperechoic aggregates are reported often in people with gout and may reflect microurate deposits, but are not specific to gout and similar small hyperechoic lesions can be seen in the setting of other conditions. Synovitis, erosions and other features of an inflammatory, erosive arthritis are identifiable with ultrasound in people with gout, but again are nonspecific for gout (Figure 2). DECT is a noninvasive method for the quantification of MSU crystals.13,14 Depending on the calibration, it is highly specific for MSU, but the sensitivity will depend on the burden and concentration of urate in the deposit or tophi being imaged (Figure 3).13 Established severe gout is usually positive but, unfortunately, DECT has reduced utility in the setting of a diagnostic dilemma of recent-onset ‘possible’ gout in which the urate burden may be low.15 Similarly, DECT is less useful in more proximal joints;13again, the atypical presentation may present a diagnostic dilemma in which a sensitive diagnostic imaging tool would be highly valuable.

Both imaging modalities need to be considered in the clinical context; the presence of hyperechoic aggregates does not imply gout in the absence of other US features or a consistent clinical picture. Similarly, urate deposition on DECT may be incidental unless a clinical picture of gout is present, and a negative DECT does not exclude gout (Figure 3).

Management

The management of gout needs to be holistic and should involve education, identification and management of modifiable risk factors for hyperuricaemia, as well as screening for and medically optimising associated comorbidities (Flowchart 1). Often, gout-specific pharmacotherapy is also required and can be divided into rapid relief for acute gout flare management and long-term ULT to reduce the risk of future flares (Table). Common misconceptions about managing gout are listed in Box 2.

Dietary risk factors for gout are listed in Box 1. Current guidelines recommend all patients with gout should receive advice regarding lifestyle modification. This includes weight loss (if appropriate and achievable), limiting alcohol (especially beer and spirits), reducing high-fructose syrups and excessive intake of meat and seafood. However, there is a paucity of evidence to suggest that dietary modification results in significant reductions in gout flares and uric acid levels, and adherence with ULT is much more effective than strict dietary changes.

Medications such as hydrochlorothiazide are known to contribute to raised serum uric acid (SUA) levels. In patients with gout who have hypertension alone, losartan is the preferential antihypertensive agent due to its modest uricosuric effects.

Acute gout flare management

The choice of anti-inflammatory agents in managing acute gout should be based on the time of initiation after flare onset, number and size of joints involved, medication contraindications and the patient’s previous experience with treatments. The drug of choice should have an appropriate degree of efficacy, lowest toxicity and be used for the shortest duration of time in order to minimise potential harm. First-line options include oral colchicine (although most useful in the first 24 hours after flare onset), NSAIDs or corticosteroids (oral, intra-articular or intramuscular) (Table). The use of topical ice in acute gout has also been shown to reduce the severity of pain and is currently recommended as an adjuvant treatment in all patients with a gout flare.16,17

Long-term urate-lowering therapy

ULT reduces SUA levels below the solubility constant for urate, allowing crystal dissolution. Effective ULT results in a reduction in the frequency and severity of gout flares and the resolution of tophi.18 A treat-to-target strategy is strongly recommended by both the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR).9,16 In patients with gout, the recommended target SUA level is below 0.36 mmol/L. An SUA target of below 0.30 mmol/L is recommended for those with severe gout (tophi, chronic arthropathy, frequent attacks) to facilitate faster dissolution of crystals.

The 2017 American College of Physicians gout management guideline reported an uncertainty of the benefit of a treat-to-target approach compared with a symptom-based strategy and placed a greater emphasis on patient-reported measures.19 However, the ACR and EULAR guidelines advocating a treat-to-target strategy provide health professionals with a simplified management directive with an objective endpoint. Importantly, the current evidence base strongly favours this approach.20

When to start a patient on ULT

ULT is strongly recommended in all patients with confirmed gout and frequent gout flares (defined as ≥2 per year), one or more subcutaneous tophi or radiographic damage attributed to gout.9,16 For patients experiencing their first gout flare, ULT is not required but should be considered in patients with chronic kidney disease of stage 3 or greater, SUA levels of 0.54 mmol/L or more, or urolithiasis. In contrast to previous recommendations, allopurinol can be initiated during an acute flare with concomitant long-term anti-inflammatory prophylaxis and this approach may aid adherence with ULT; however, evidence of long-term effectiveness of this approach is lacking.21

Choice of ULT

Allopurinol, a xanthine-oxidase inhibitor, is the preferred first-line agent for ULT due to its effectiveness, cost and safety.9,16 Allopurinol is generally well tolerated but may cause diarrhoea, skin rashes, nausea and vomiting. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions are well described with allopurinol and can be mitigated by using lower starting doses, particularly in patients with renal impairment (in whom the starting dose should be lowered according to creatinine clearance). A genetic predisposition to severe cutaneous adverse reactions to allopurinol associated with the HLA-B*5801 allele is recognised in Southeast Asian (e.g. Han Chinese, Korean, Thai) and African American populations. Genetic testing is recommended in high-risk individuals, as allopurinol therapy is contraindicated.

Febuxostat, also a xanthine-oxidase inhibitor, is the recommended second-line agent for those who cannot tolerate allopurinol.16 Significant concerns over the cardiovascular safety of febuxostat have arisen from the Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients with Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities (CARES) study. In this study of over 6000 people, febuxostat was associated with a higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than allopurinol in people with established cardiovascular disease.22 As a result, febuxostat is not recommended in patients with pre-existing major cardiovascular disease, including ischaemic heart disease, cardiac failure, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with evidence of microvascular or macrovascular disease.23 Importantly, in the recently published study on the long-term cardiovascular safety of febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with gout (Febuxostat versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial; FAST) study, febuxostat was found to be non-inferior to allopurinol therapy with respect to the primary cardiovascular endpoint.24 These findings are reassuring, but the slight difference in study population to the CARES study should be considered. In the CARES study, all patients had a history of major cardiovascular disease, whereas in the FAST trial, only one-third had prior cardiovascular disease, and those with a recent cardiovascular event or severe heart failure were excluded.

Probenecid is a uricosuric agent usually reserved for those who are intolerant of or fail to respond to the xanthine-oxidase inhibitors. Its efficacy is reduced in the setting of renal impairment, therefore, it has limited utility in many people with gout.

Current recommendations are to commence ULT at a low dose, to reduce the risk of adverse events (Flowchart 2). The dose should be increased in small increments every two to four weeks as required, guided by SUA until the target level is achieved. If the SUA target cannot be reached at maximum-tolerated doses, patient adherence should be explored, and consideration given to switching to an alternative ULT. Combination ULT is sometimes required.

Flare prophylaxis during ULT

Concomitant flare prophylaxis with anti-inflammatory therapy (typically colchicine) is recommended during the initiation and uptitration of ULT. This should be continued for at least three to six months, but may be required for longer periods if the patient continues to experience recurrent flares. Colchicine specifically has been shown to be cost-effective in the Australian population.25 Although international guidelines do not make recommendations regarding the preferred anti-inflammatory therapy, low-dose colchicine is arguably safer than long-term prednisolone or NSAIDs.

Barriers to optimal care

Evidence from around the world has consistently indicated that the management of gout is poorly implemented.26-30 Australian evidence showed that about 50% of people with gout were on ULT and that less than a quarter were at target serum urate levels at any point in time over a five year period.5,6 Despite efficacious therapies, relatively consistent recommendations about how to use these therapies and clear objective targets, gout remains undertreated.

Difficulties in achieving target urate levels and subsequent control of gout are multifactorial. These include underprescription of or failure to uptitrate ULT, and patients failing to initiate and persist with therapy or undergo urate monitoring.4,6,28 Educating healthcare professionals is important to improve outcomes for people with gout, but this must occur in parallel with educating people with gout and the community at large.

Australian evidence suggests that optimal outcomes are not being achieved with the current gout management pathways, and alternative management pathways need to be considered. Evidence from international studies has shown that healthcare pathways using nurse- or pharmacist-led care resulted in higher rates of therapeutic targets achieved in patients with gout.31-33 These paradigms focus on either education or protocol-driven uptitration of ULT, or a combination of both.34-36 A large study undertaken in the UK reported that a nurse-led intervention was cost-effective and efficacious, with 95% of participants achieving target urate levels at two years.33 It is postulated that nurses can spend more time with each patient, providing more education and exploration of patient concerns, translating to greater behavioural change. The use of technology to provide telehealth appointments and implement electronic-based reminders has also been shown to improve gout management in primary care.37

As with most research-based active interventions, it remains to be seen whether these novel care pathways can be incorporated into the Australian healthcare context, but they illustrate the efficacy of simple interventional strategies, namely education and an objective therapeutic algorithm.

Conclusion

Gout is a common condition that is associated with significant costs. The burden on the community is rising as the prevalence rises. Despite effective therapies and the availability of structured management guidelines with an objective target, the outcomes for people with gout are poorer than they should be. Optimal management of this disease is achievable and GPs, as medical experts in the community, are well placed to improve outcomes for people with gout. MT