Interstitial lung disease – from initial investigations to treatments, shared care and beyond

- Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is characterised by progressive scarring of the lungs, leading to respiratory failure and a high symptom burden.

- High-resolution CT of the chest with prone views is the investigation of choice when assessing for ILD.

- A low threshold should be applied for investigating patients presenting with persistent cough or dyspnoea with risk factors for ILD including connective tissue disease, occupational exposure, certain drug therapies and a family history.

- Expanded PBS access to antifibrotic therapy (nintedanib) for any patients with ILD who exhibit progressive fibrosing features offers an opportunity for improved patient outcomes with early disease identification and access to respiratory services.

- Blood monitoring is required lifelong for patients taking antifibrotics or steroid-sparing ILD treatments.

- Collaborative GP and specialist management will be essential with the imminent increase of ILD referrals following the introduction of nationwide lung cancer screening in 2025.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is an umbrella term for a group of diseases affecting the lung interstitium, which may or may not be progressive. Although historically considered rare, ILD is becoming increasingly prevalent as our understanding of its diversity grows and diagnostic pathways improve. It is often associated with progressive destruction of the lung interstitium or airway and vessels, resulting in respiratory failure, substantial symptom burden, healthcare cost and death.1 Access to treatment, and specifically antifibrotic therapy that can slow disease, has expanded and so the onus to correctly identify and diagnose ILD early should be a priority. This article provides an overview of the investigations, treatments and management approaches for ILD.

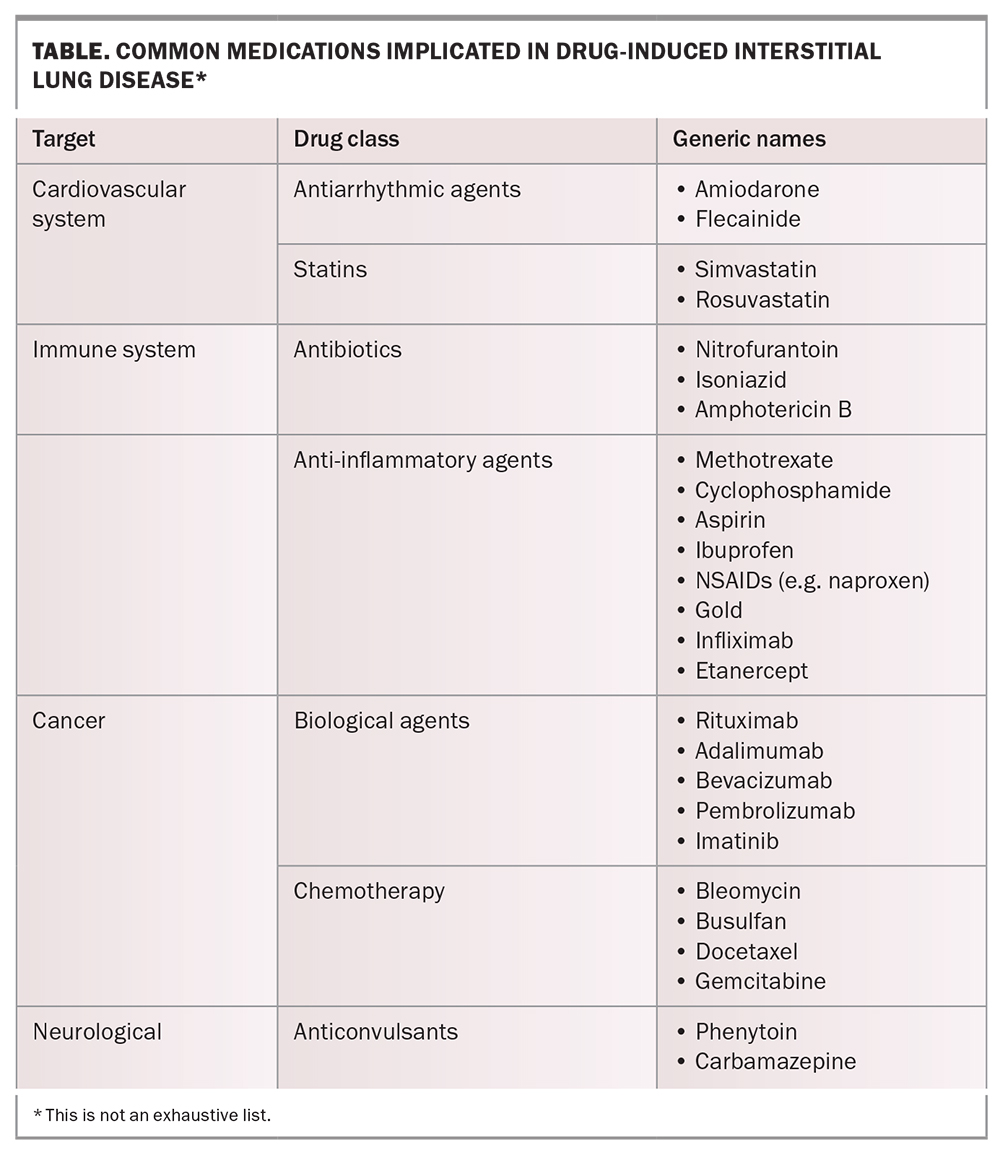

Recognising ILD in a patient can be complex, given the spectrum of disease and clinical phenotypes. A low threshold should be employed when investigating patients presenting with a persistent cough (defined as lasting more than eight weeks) or insidious exertional dyspnoea over months to years.2 Furthermore, an understanding of concurrent risk factors for the development of ILD should prompt more formal assessment. Examples include advanced age; a positive family history of ILD; occupational dust exposure from asbestos, silica (stonemasons) or farming; or co-existent connective tissue disease, such as scleroderma or rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Drug toxicity resulting in ILD (drug-induced ILD) is also an emerging threat, particularly with the increased use of immunotherapy agents in cancer treatment, but common agents such as nitrofurantoin and amiodarone should be used with caution (Table).3

ILD classification

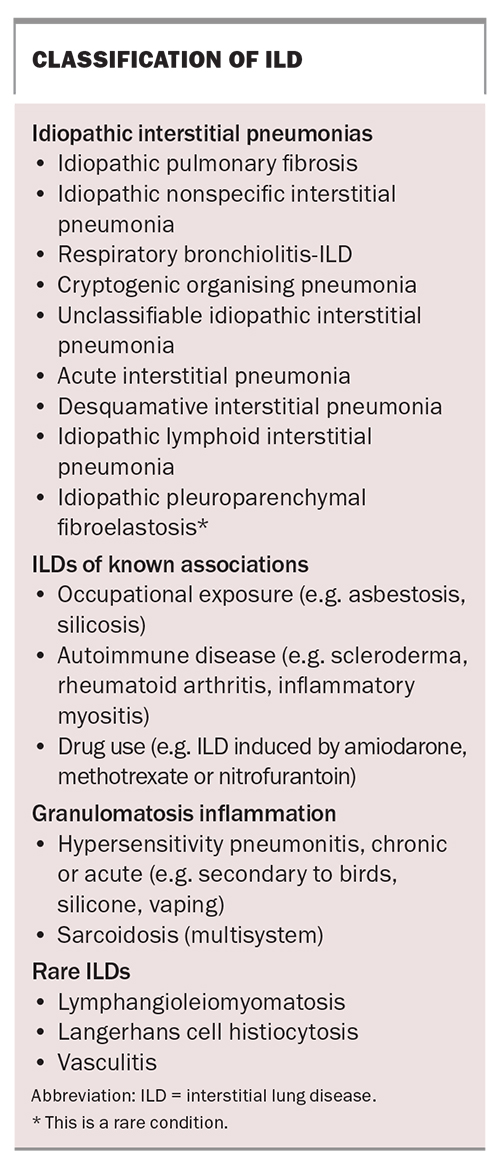

ILD is defined according to clinical, radiological, serological and histopathological features. Discussions at dedicated ILD multidisciplinary meetings (MDMs) are recommended to improve the accuracy of diagnosis.4 Broadly speaking, ILD can be split into four main categories (Box). The first category comprises idiopathic interstitial pneumonias; in this category, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common, followed by idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and respiratory bronchiolitis ILD. The second category comprises ILDs of known associations, which include ILDs induced by occupational exposure, connective tissue disease and drugs. The third category is characterised by granulomatous inflammation, including hypersensitivity pneumonitis (to birds, silicone or solvents) and sarcoidosis. The fourth category contains rare ILDs, such as lymphangioleiomyomatosis and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Investigations for ILD

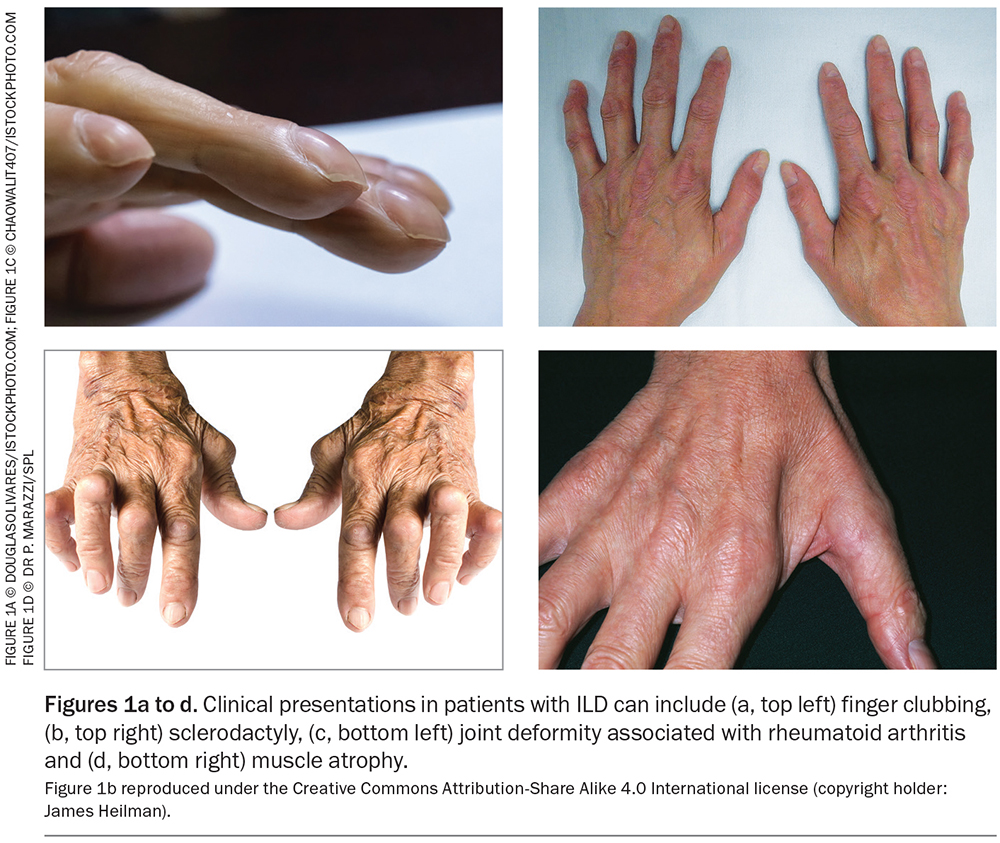

On clinical examination, patients with ILD may present with finger clubbing or features of connective tissue disease such as sclerodactyly (thickened skin), nail fissuring or Raynaud’s phenomenon (associated with scleroderma), joint deformities (associated with RA) or muscle weakness and atrophy myositis, as shown in Figure 1. Resting and exertional oxygen saturations are helpful as both a baseline functional measurement and to detect early progression or deterioration. Patients with ILD typically have marked exertional hypoxaemia, which is more severe in patients with IPF compared with other forms of ILD.5 Often, chest auscultation reveals fine bibasal inspiratory crackles. It is important to exclude other causes of cough and dyspnoea, particularly co-existent heart failure, which has similar chest auscultatory findings.

The single most important diagnostic tool in ILD assessment is high-resolution computed tomography of the chest. This imaging modality enables the differentiation between true ILD and, for example, heart failure or dependent change. If available, lung function testing often demonstrates a restrictive lung pattern: reduced forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) with preserved FEV1/FVC. More specific blood testing, which can be reserved until formal respiratory review occurs, is used to assess for antibodies suggestive of underlying connective tissue disease.

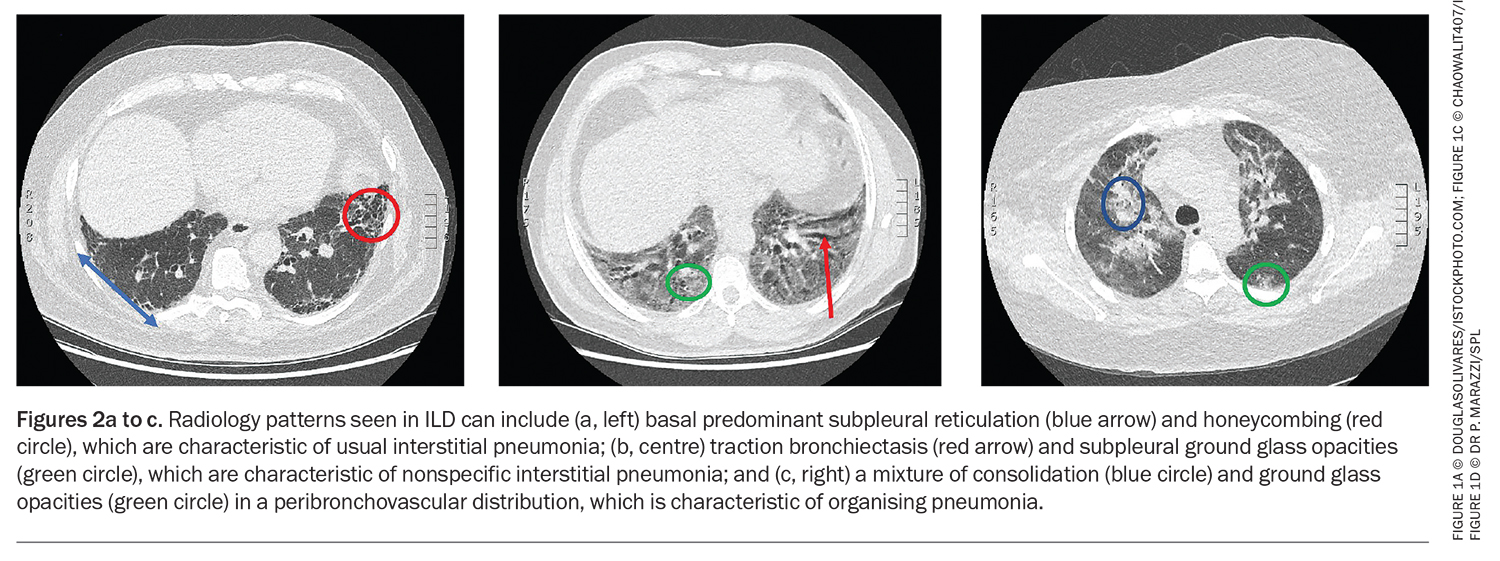

Radiology nomenclature can be confusing to the non-ILD physician. Radiology describes the pattern and distribution of disease, and possible clues to the underlying process. Examples of the latter include pleural plaques (indicating asbestos exposure), calcified lymph nodes (perhaps reflecting granulomatous disease or silicosis) or air trapping (seen in hypersensitivity pneumonitis). Commonly described ILD patterns include usual interstitial pneumonia, NSIP and organising pneumonia (OP) (Figure 2). It is important to note that the radiology pattern is only part of the overall clinical diagnosis of ILD, and it is not uncommon to observe two or more patterns (e.g. NSIP/OP overlap).

Additional investigations usually conducted after formal respiratory assessment can include bronchoscopy, in-depth lung function testing (including lung volume, diffusing capacity and six-minute walk test) and surgical lung biopsy or lung cryobiopsy. After all objective testing is performed, the physician presents the case at their local ILD MDM to facilitate a clinical diagnosis and management plan.

Treatments for ILD

Medical therapies for ILD

There are two main types of medical therapy for ILD: antifibrotics (nintedanib and pirfenidone) and immunosuppression (prednisolone and steroid-sparing agents, such as mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine and rituximab). Following the outcome of the PANTHER trial, which recognised that immunosuppression can be fatal in patients with IPF, it is increasingly important to define the ILD development process.6 Some ILDs have a more inflammatory component, such as scleroderma-related ILD, and hence, the treatment involves immunosuppression. Other ILDs, such as IPF, are treated with antifibrotic therapy, which can slow the rate of disease progression by 50% per year on average.7,8 Additional drugs and new compounds are in the pipeline, but a cure for ILD is yet to be established, and this must be conveyed to the patient in an empathetic way.

There has been increasing evidence for antifibrotic therapy outside the IPF cohort. As of May 2022, the PBS allows the prescribing of nintedanib to any patient with ILD who demonstrates progressive fibrosing features (defined as a reduction in the relative FVC of greater than 10%, or 5 to 10% combined with increased fibrosis on high-resolution CT or deterioration in symptoms, over two years). This was a very welcome addition to the PBS by the ILD community as many non-IPF ILDs, such as unclassifiable disease, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and RA-associated ILDs, can have equally poor outcomes despite treatment, often with immunosuppressants. It must be noted that not all ILDs progress, although reassessment with objective parameters is encouraged in patients with ILD experiencing increasing symptom burden.

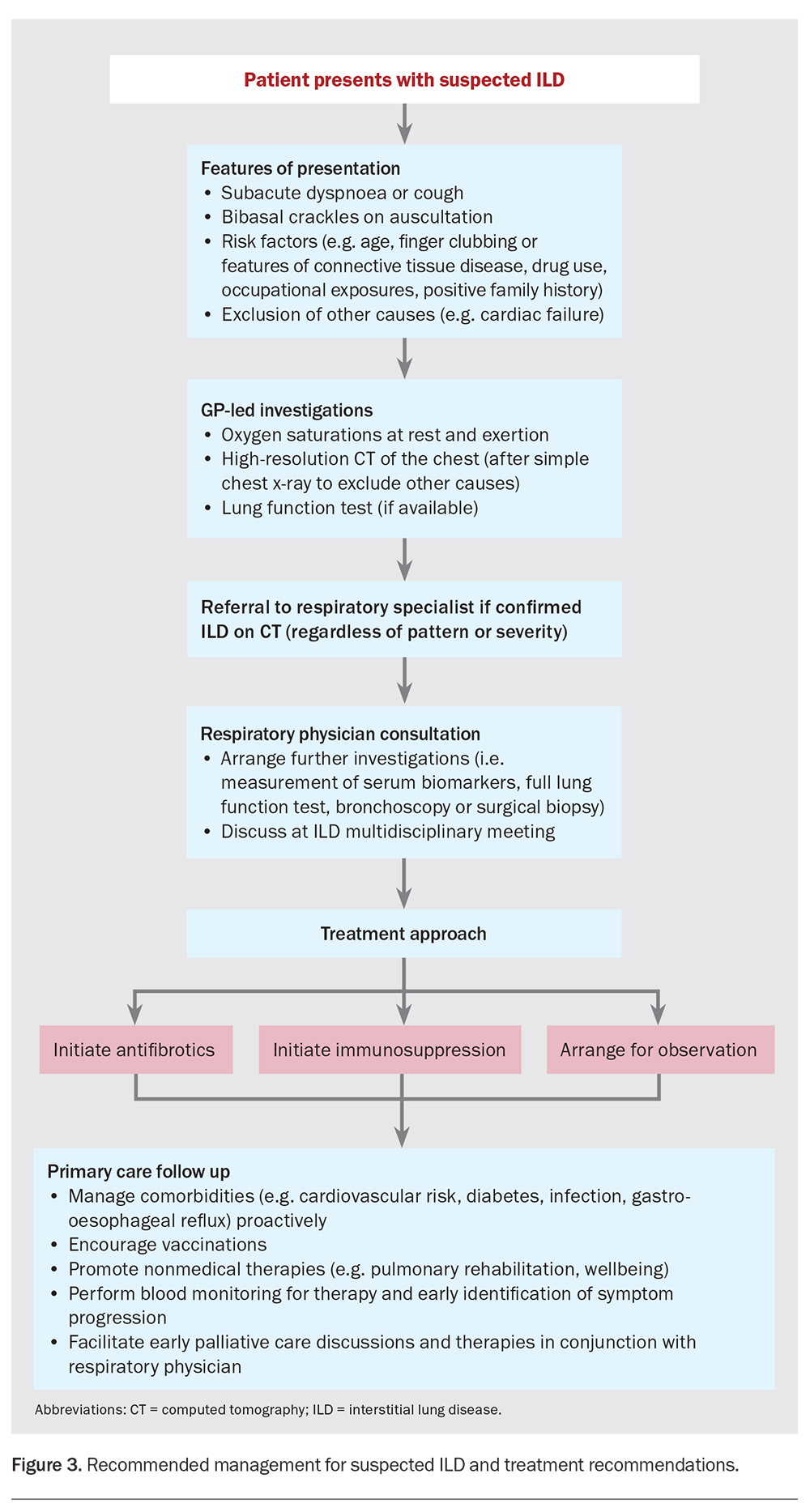

Figure 3 demonstrates an investigation and treatment pathway for common ILDs. Importantly, treatment is not always instigated at diagnosis, as not all ILDs progress. Risk and benefit assessments are conducted on a regular basis considering objective changes (CT and lung function test findings) and patient preference.

Nonmedical therapies for ILD

Studies have demonstrated a positive role for pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with ILD with further evidence to suggest patients should be reassessed every few years for the continued need for pulmonary rehabilitation because of the progressive nature of the disease.9 Patients may also benefit from breathing techniques, the use of handheld fans and participation in support groups.

Primary care-specific management of ILD

Patients with ILD may have a prognosis of less than six months to beyond 10 years depending on the ILD type, severity and co-existent comorbidities. Therefore, engagement with colleagues in primary care is essential in managing the adverse effects of treatment and chronic illness. Like with any respiratory disease, vaccinations are strongly encouraged as is managing co-existent disease known to increase the risk of exacerbation, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, infection and obstructive sleep apnoea.10,11

Immunosuppression

Patients receiving treatment with glucocorticoids and steroid-sparing agents require careful proactive treatment of cardiovascular risk, type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, gastroesophageal reflux and infection. When steroid-sparing agents are administered, blood monitoring is often required, usually every three to six months, for hepatic dysfunction, lymphopenia and anaemia.

Antifibrotics

Both nintedanib and pirfenidone have recognised common adverse effects. Nintedanib can predispose patients to mild to severe diarrhoea with nausea, whereas pirfenidone can be associated with nausea and photosensitive rash. Both drugs can result in mild to severe hepatic dysfunction. In the event of these adverse reactions occurring, it is advised to liaise with the hospital ILD nurse or ILD physician. Simple management may consist of antiemetics or antidiarrhoeal agents, as well as dietary advice and drug timing. In severe cases, drug disruption or complete cessation may be advised, with the latter more commonly seen in cases of significant hepatic dysfunction. Antifibrotics also require blood monitoring more frequently in the first three to six months and then less frequently thereafter. Idiosyncratic hepatic toxicity can occur at any time on either medication.

Acute exacerbations

Unfortunately, acute exacerbations of ILD have limited treatment options and often worsen the trajectory of the underlying disease.10 It is important to exclude specific causes of worsening respiratory symptoms, such as infection, pulmonary embolism or cardiac failure, and early discussion with the patient’s ILD physician is encouraged.

Palliative care

Many patients with ILD who have true progressive fibrosing disease will develop respiratory failure. This is often associated with debilitating symptoms of extreme dyspnoea or cough. Introducing holistic palliative care early for symptom management and advanced care planning is often initiated in secondary care but can also be facilitated by GPs. Medical therapies such as oxygen, opioids and benzodiazepines have a role in palliative care.

Future directions

With the imminent arrival of nationwide lung cancer screening in 2025, it is anticipated that the number of referrals to respiratory medicine specialists with possible (interstitial lung abnormality) or suspected ILD based on incidental CT findings will strain resources and potentially slow access to secondary care level assessment. Therefore, we should proactively create and support primary care pathways to enable early diagnosis, ILD MDM discussion and commencement of treatment, with early transition to the community for disease and therapy monitoring.

Conclusion

ILD is characterised by a diverse spectrum of disease but is often associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Treatment with antifibrotic agents for progressive phenotypes is now much more accessible, highlighting the importance of early disease identification and referral to a respiratory centre to facilitate MDM discussion and treatment planning. Shared care between GPs and specialists needs greater commitment, allowing for the upcoming surge in ILD referrals with the rollout of lung cancer screening. A well-balanced, collaborative approach will benefit both healthcare professionals and patients. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Moore is a Committee Member of the Australasian ILD Registry.

References

1. Wysham NG, Cox CE, Wolf SP, Kamal AH. Symptom burden of chronic lung disease compared with lung cancer at time of referral for palliative care consultation. Ann Am Thorac Society 2015; 12: 1294-1301.

2. Simpson G. Investigation in chronic lung disease. Aust Fam Physician 2010; 39: 94-99.

3. Schwaiblmair M, Behr W, Haeckel T, Märkl B, Foerg W, Berghaus T. Drug induced interstitial lung disease. Open Respir Med J 2012; 6: 63-74.

4. Lee CT. Multidisciplinary meetings in interstitial lung disease: polishing the gold standard. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2022; 19: 7-9.

5. Otake K, Misu S, Fujikawa T, Sakai H, Tomioka H. Exertional desaturation is more severe in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis than in other interstitial lung diseases. Phys Ther Res 2023; 26: 32-37.

6. The Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1968-1977.

7. King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2083-2092.

8. Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2071-2082.

9. Dowman L, Hill CJ, May A, Holland AE. Pulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; 2: CD006322.

10. Kolb M, Bondue B, Pesci A, et al. Acute exacerbations of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev 2018; 27: 180071.

11. Kim DS. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Encyclopedia of Respiratory Medicine 2022: 199-217.