Psoriatic arthritis: how early recognition helps management

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease with diverse musculoskeletal and nonmusculoskeletal manifestations, which makes diagnosis difficult. Early recognition and treatment of symptoms, including assessing for risk factors and common comorbidities, as well as early referral to a specialist, can help improve disease outcomes. New targeted therapies are available under specialist guidance for patients with moderate to severe disease.

- Early recognition of the clinical features of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is crucial to prevent joint damage and disability. Consider PsA in patients who present with a swollen heel, digit or joint, particularly those with a personal or family history of psoriasis.

- PsA has diverse clinical presentations including both musculoskeletal and nonmusculoskeletal manifestations. As well as joint inflammation, GPs should look for disease involvement in skin, nails, eyes and the gastrointestinal tract.

- There are no laboratory biomarkers specific for the diagnosis of PsA. Test results for human leukocyte antigen B27 are often negative and inflammatory marker levels may be low.

- Patients with PsA are at increased risk of comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes and depression. GPs play a central role in monitoring and optimising management of these conditions.

- Multidisciplinary input is beneficial and early referral to a rheumatologist is recommended for all patients with PsA.

- The severity of disease and the extent of joint and organ involvement determines the approach to treatment of PsA. Patients with moderate to severe disease warrant early escalation to disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, inflammatory musculoskeletal disease that affects an estimated 0.1 to 1% of the population and 15 to 30% of patients with psoriasis.1 PsA is a notably heterogeneous disease with clinical features that may vary between individuals and evolve over time. PsA may manifest as axial or peripheral arthropathy (or both), dactylitis and enthesitis, all of which can lead to progressive joint damage and disability. Early identification of at-risk individuals, diagnosis and intervention are therefore crucial to patient outcomes.

Nonmusculoskeletal manifestations include psoriatic skin and nail lesions, as well as gastrointestinal, ocular, pulmonary and urogenital disease. Patients with PsA also have an increased prevalence of cardiovascular, metabolic and neuropsychiatric comorbidities, due in part to the chronic systemic inflammation, which further increases the burden of morbidity and mortality in this population.2

Effective management of PsA requires early referral of the patient to a rheumatologist and collaborative management of their comorbidities. GPs play an important role in detecting early features of PsA, monitoring for systemic involvement and optimising overall patient wellbeing with regards to long-term infection and metabolic risk.

Pathophysiology of psoriatic arthritis

The pathophysiology of PsA stems from a complex interplay between immunogenetics and environmental factors. PsA arises from dysregulation of the interaction between the innate and adaptive immune systems.3 It is therefore considered an overlap autoimmune and autoinflammatory condition. Stimulation of dendritic cells results in their overactivation, which initiates a cascade of proinflammatory cytokines. This includes the proliferation of interleukin (IL)-23 and IL-12, which leads to the differentiation of T helper (Th)17, type 3 innate lymphoid and gamma-delta T cells, and Th1 cells, respectively. Differentiation into these effector Th cell populations further stimulates synthesis of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, IL-17 and IL-22, thereby causing inflammation, erosive bone destruction and osteoproliferation.4

PsA appears to have a genetic basis involving class-I human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), non-HLA major histocompatibility complex genes and genetic elements beyond the major histocompatibility complex region. These genetic components are linked to distinct clinical phenotypes within PsA. For instance, enthesitis and dactylitis are associated with HLA-B27, whereas axial disease is associated with the HLAs -B27, -B38, -B39 and -B08.5 Most identified genetic factors lead to a heightened susceptibility to PsA but lack the individual potency to directly cause disease. As such, there are no clear identifiable genetic biomarkers for the diagnosis of PsA. In Australia, the prevalence of HLA-B27 in the general population ranges from about 5 to 15%.6 Moreover, the proportion of patients with PsA who are HLA-B27 positive varies between populations, ranging from 20 to 35%.7 It is therefore important to recognise that a negative HLA-B27 test result does not exclude the diagnosis of PsA.

Environmental triggers such as infections, mechanical stress, joint or enthesitis trauma and disruptions to the normal skin and gut microbiome contribute to dysregulated activation of innate immune cells and result in tissue damage.8 In individuals genetically predisposed to PsA, this aberrant immune response leads to a range of disease manifestations, including skin, joint and soft tissue pathology, as well as internal organ involvement. The severity and trajectory of PsA can greatly differ among individuals, and is influenced by genetic predisposition and environmental triggers.

Clinical manifestations of psoriatic arthritis

Substantial variation in disease manifestations exists among individuals with PsA due to the clinical culmination of the pathological processes involved in the disease.

Articular manifestations

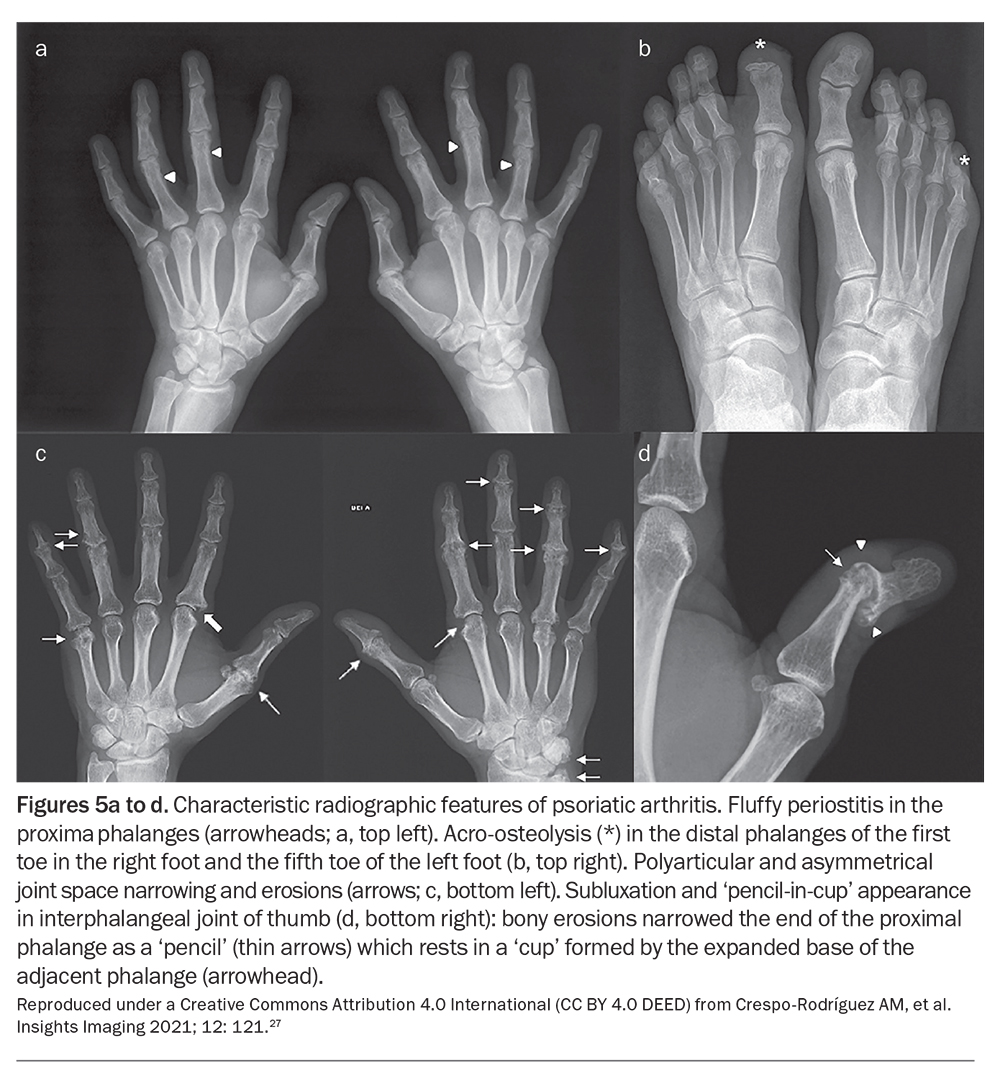

Articular involvement in PsA can be classified into five distinct but overlapping subsets: symmetrical polyarthritis, asymmetrical oligoarthritis, distal interphalangeal (DIP) arthritis, spondyloarthropathy and arthritis mutilans. Among these subsets, the asymmetric oligoarticular pattern of disease is the most common form at initial presentation. However, the DIP arthritis pattern emerges as the predominant type overall, accounting for about 40 to 60% of cases.5 PsA with an axial component may present similarly to ankylosing spondylitis; however, compared with ankylosing spondylitis, axial PsA displays a much lower correlation with HLA-B27, tends to affect men and women equally and demonstrates asymmetric involvement with less radiological evidence of sacroiliitis.9 Arthritis mutilans represents the rarest and most severe phenotype. It predominantly affects the small joints of the hands, causing pronounced bone resorption and subluxation, along with the phenomena of digital telescoping and the formation of ‘pencil-in-cup’ deformities.5

Enthesitis is inflammation at points where ligaments, tendons and joint capsules attach to bone, and is a hallmark trait of PsA.10 It can present as the initial prominent manifestation of disease, often appearing in the lower extremities, and results in substantial pain and functional impairment. The insertions of the Achilles tendon and the plantar fascia are the most commonly affected sites of enthesitis in PsA. Over time, persistent inflammation contributes to structural changes, including bony erosions and reactive periosteal changes, such as the formation of spurs and syndesmophytes.9

Diagnosing enthesitis related to PsA can be challenging because mechanical causes of inflammation at these sites, such as from an injury or repetitive movement, are also common. Patients with autoinflammatory enthesitis may describe typical inflammatory features without an identifiable traumatic event and, in contrast to mechanical enthesitis, will have limited response to physical therapy. On clinical examination, palpation elicits pain at entheseal sites, accompanied by swelling and erythema. Enthesitis is significantly associated with poorer functional status and quality of life in patients with PsA, including greater pain at affected joints and fatigue.11

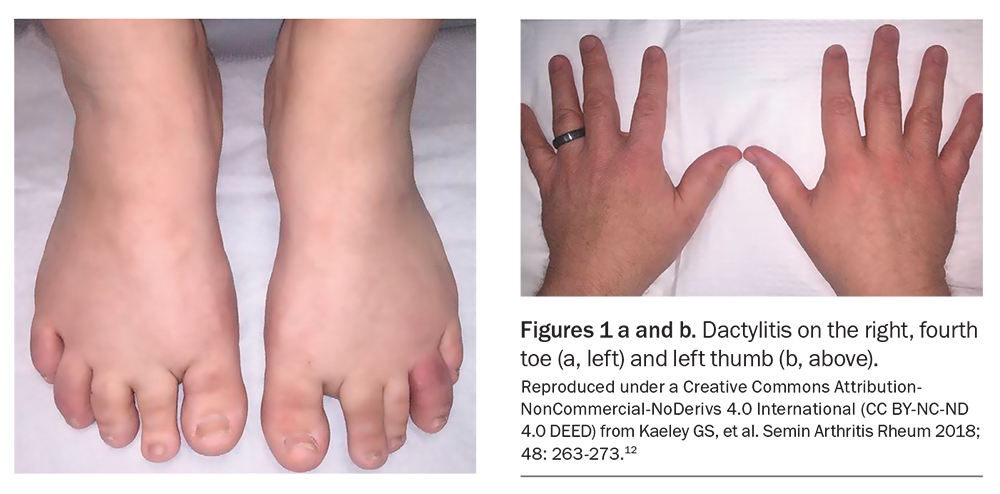

Dactylitis, otherwise known as sausage- like digit, is also a pathognomonic manifestation of PsA. It results from diffuse swelling of the digit due to synovitis, tenosynovitis and soft tissue inflammation. These changes can be acute, involving painful inflammation, or chronic where swelling persists even after the pain has long subsided (Figure 1).12

Extra-articular manifestations

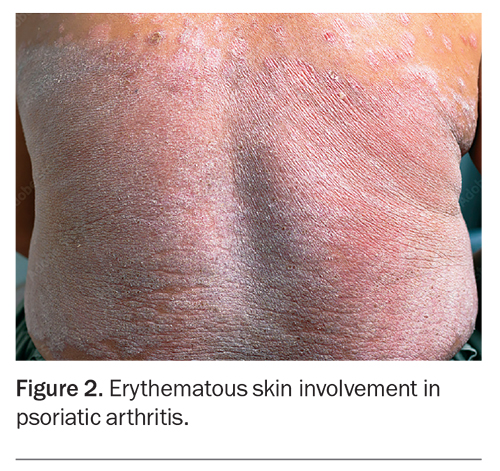

Psoriatic skin and nail disease often precede the onset of arthritis. Although PsA develops in about 15 to 30% of individuals who have psoriasis, it is important to recognise that not all patients with PsA exhibit psoriasis.13 The severity of psoriatic skin disease also correlates poorly with the severity or development of joint disease. Chronic plaque psoriasis, characterised by well-demarcated, scaly plaques, is the most common skin manifestation in PsA. Other phenotypes include guttate psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, palmoplantar psoriasis and, more rarely, erythrodermic psoriasis and generalised pustular psoriasis.14 The latter two may present with acute attacks of generalised erythematous skin involvement with systemic symptoms (Figure 2).

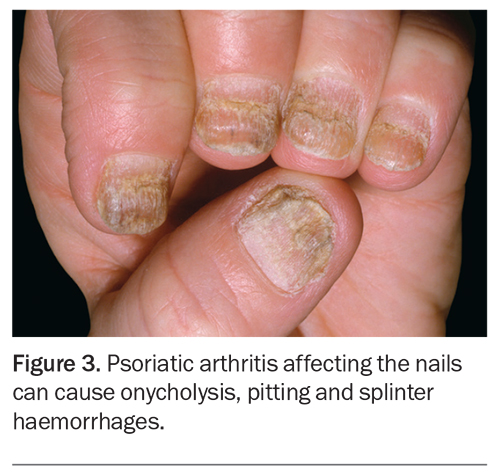

Nail involvement in the form of onycholysis, pitting and splinter haemorrhages is frequently observed in PsA and can impact greatly on a patient’s function and quality of life (Figure 3).15 PsA sine psoriasis is characterised by rheumatological manifestations of dactylitis, DIP arthritis and enthesitis, in the absence of cutaneous lesions. In these patients, a family history of psoriasis is sufficient to fulfil diagnostic criteria of PsA.16

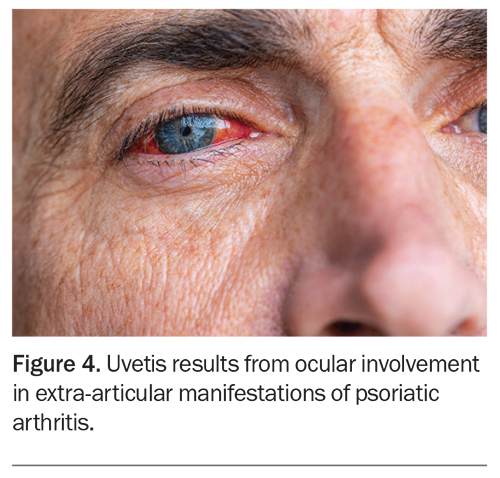

Ocular involvement is one of the most frequently occurring extra-articular manifestations of PsA after skin disease. Uveitis has been recognised as the most common ocular manifestation but other conditions including conjunctivitis, iritis and episcleritis also occur (Figure 4).17 Patients with PsA have an increased prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease, both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Although common susceptibility genes identified in genome-wide association studies could potentially account for this correlation, there is currently limited evidence to support a direct causative relationship.18 Nonetheless, clinicians should remain mindful of the increased risk of gastrointestinal disease in these patients and perform further investigations as indicated.

Comorbidities

A significant proportion of morbidity and mortality in PsA can be linked to comorbidities that are not inherent to the disease; rather, they arise from chronic disease processes or the treatment of PsA. People with PsA experience significantly increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease, including hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, and major cardiovascular events, and it is the leading cause of mortality among these patients.19 This may be attributable to unconventional risk factors, such as chronic inflammation and elevated homocysteine levels, which are poorly accounted for in conventional risk stratification tools such as the Framingham Risk Score (FRS).20 Cardiovascular risk among patients with PsA is, therefore, often underestimated. These patients face a risk exceeding 10% for cardiovascular disease within 10 years of diagnosis.21 Regular screening and tight control of underlying metabolic risk factors in the primary care setting have the potential to greatly improve prognosis for these patients.

Mood disorders such as depression and anxiety are more prevalent in patients with PsA compared with the general population and are often associated with disability, chronic pain and fatigue.22 A review of recent epidemiological data explored the link between systemic inflammation and transcriptional modulation of the central nervous system as a potential mechanism for the development of neuropsychiatric manifestations in PsA.23

Diagnosing psoriatic arthritis

Diagnosing PsA, particularly at the onset of symptoms, can be challenging. Although psoriasis typically precedes joint involvement in most patients, it is important to note that the presence of psoriasis is not a requirement for the diagnosis of PsA. As such, a heightened clinical suspicion is needed for patients with a personal or family history of psoriasis. As previously mentioned, although HLA-B27 is linked to other spondyloarthropathies, it is less consistently associated with PsA.24 Test results for rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies are typically negative. Acute phase reactants, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, are only variably elevated in less than half of patients and, therefore, low levels cannot exclude the diagnosis.25

As there are no biomarkers specific for PsA, it is largely a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of psoriasis and inflammatory arthritis, enthesitis or spondylitis, along with other typical features such as nail lesions and dactylitis. Imaging modalities such as plain radiography, CT, ultrasound and MRI serve as useful adjuncts to diagnosis. Although not necessary to make a diagnosis of PsA, the characteristic radiographic patterns of concurrent bone destruction and juxta-articular bone formation, as well as axial changes including sacroiliitis and syndesmophyte formation, can help support the diagnosis.26 Examples of the characteristic radiographic features of PsA are shown in Figure 5.27

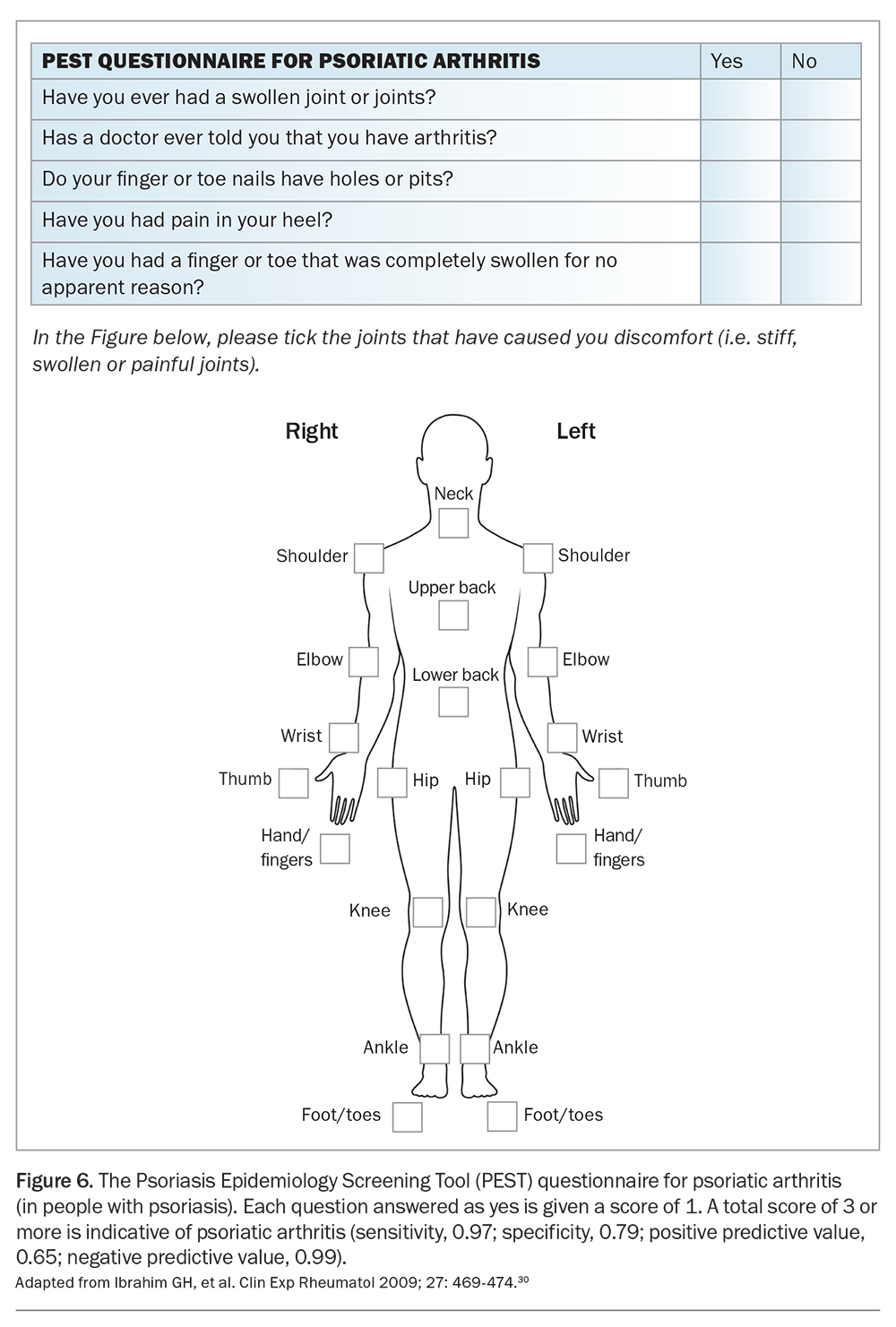

In the primary care setting, screening tools such as the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire, the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic patients (EARP) questionnaire and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) may be useful in the early identification of patients with potential PsA.28-30 The PEST screening questionnaire for PsA in patients with psoriasis (Figure 6) can be is useful in both primary care and tertiary settings.30 These tools incorporate patient-reported measures and clinical examination findings to determine which patient should be referred for further rheumatological assessment and avoids the need for extensive laboratory or radiological investigations. Recent studies showed comparable performance between different screening tools, and the choice of which to use depends on factors such as simplicity and minimising patient burden.31

In patients presenting with suspected PsA, early use of a validated clinical screening tool, investigations (including in the presence of negative rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide results), plain radiography of the hands, feet and axial skeleton, and early referral to a rheumatologist are recommended.

Management of psoriatic arthritis

PsA is a heterogeneous and often severe disease, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach for effective management. The aim of treatment is to reduce disease activity, achieve remission and enhance the patient’s overall quality of life. Musculoskeletal and nonmusculoskeletal manifestations, as well as comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease and depression, should be addressed.32 Shared decision-making between patients and healthcare providers is therefore central to balancing treatment efficacy, safety and costs.33,34 It should be emphasised that the choice of disease-modifying therapies for patients with PsA, and their review, should be undertaken by a specialist.

Initial management

The stepwise approach to treatment is guided by disease severity and the extent of joint and organ involvement. In patients with oligoarticular or axial disease, NSAID monotherapy in combination with local glucocorticoid injections may be adequate to relieve musculoskeletal symptoms. These measures may be trialled for four weeks in patients with oligoarthritis, and up to 12 weeks in those with entheseal or axial predominant disease. Physiotherapy may also help to preserve function and spinal mobility in patients with axial involvement.35

Specialist management

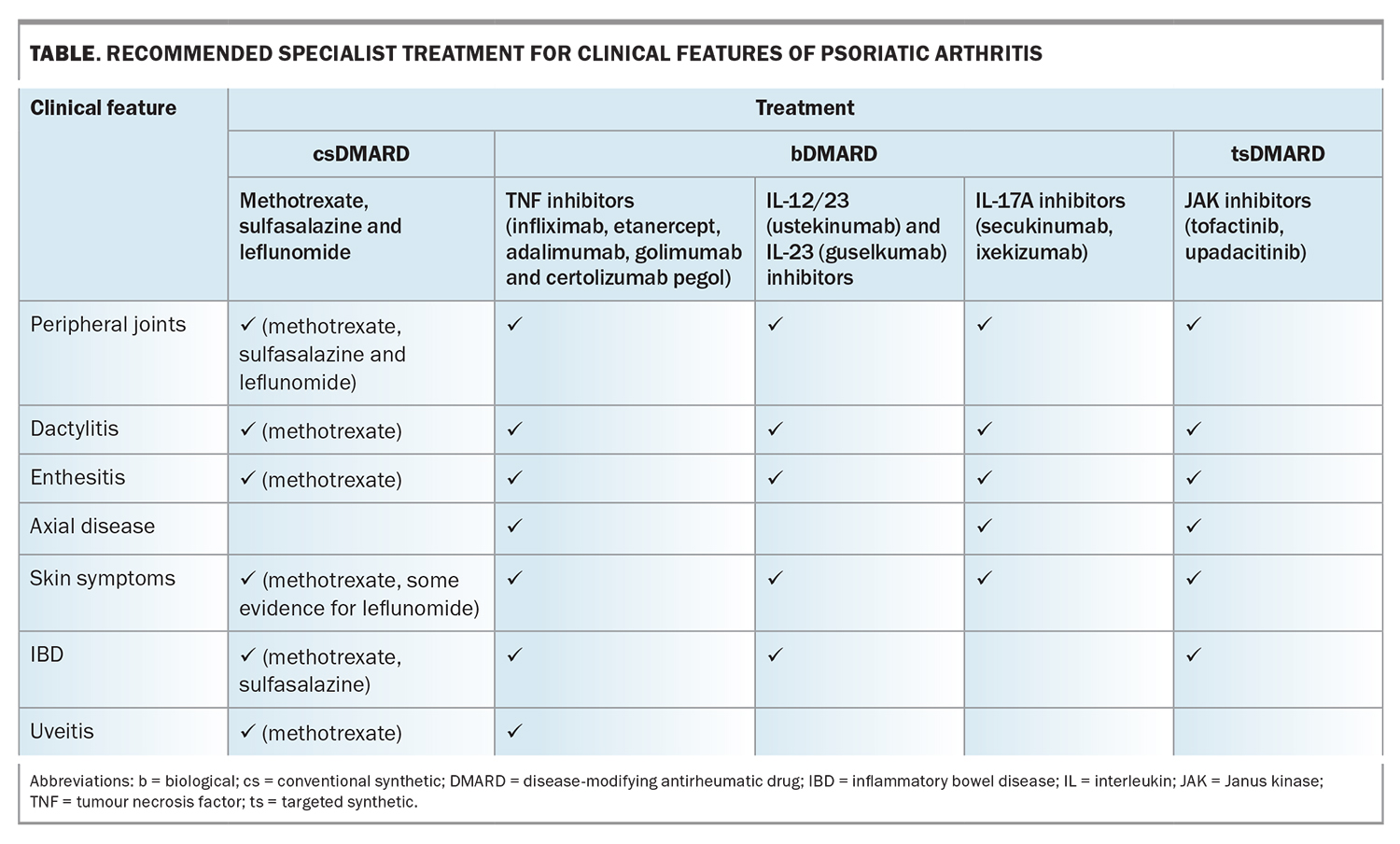

Specialist referral should be sought if initial therapies do not achieve treatment targets. Recommended specialist prescribed treatment modalities for specific manifestations of PsA are summarised in the Table. If disease activity persists beyond four weeks, patients with peripheral arthritis should be started on a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD), such as methotrexate, leflunomide or sulfasalazine.36 Traditionally, csDMARDs have been shown to be ineffective in axial or entheseal PsA. However, a recent randomised controlled trial of patients with early PsA demonstrated improvement in enthesitis with methotrexate monotherapy.37 For patients with axial or entheseal disease who have not responded to NSAIDs, physiotherapy or local glucocorticoid injections, a biological (b)DMARD (such as a TNF or IL inhibitor) or targeted syntheric (ts)DMARD (such as a Janus kinase [JAK] inhibitor) is recommended.38

Initial treatment with a csDMARD is indicated for treatment-naïve patients with moderate to severe peripheral arthritis, particularly in those with polyarticular disease. Patients with poor prognostic factors, including structural damage in the presence of inflammation, high inflammatory marker levels or extra-articular manifestations, should also be considered for early escalation to a csDMARD.39 Methotrexate has proven efficacy in skin psoriasis and remains the recommended agent for patients with relevant skin involvement, defined as more than 10% body surface area involvement or as affecting a patient’s quality of life. Combination csDMARD therapy, such as methotrexate and leflunomide, can improve control of disease activity in PsA. However, combination therapy is typically less well tolerated and is associated with an increased risk of adverse events.40 In Australia, patients are required to trial two csDMARDs over a minimum period of three months before they are eligible for PBS subsidised tsDMARD or bDMARD therapy. csDMARDs are recommended as first-line therapy because of their favourable balance in relative efficacy and costs when compared with biologics.

The presence of musculoskeletal and nonmusculoskeletal manifestations and relevant comorbidities influence the choice of initial bDMARD therapy. In patients with PsA and peripheral arthritis, there is no evidence favouring the efficacy of one bDMARD over another and current recommendations do not differentiate between the use of TNF, IL-23, IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors for these patients. The use of IL-12/23 inhibitors is not recommended in patients with predominantly axial disease. If such patients have an inadequate response to NSAIDs, they should be considered for a bDMARD in the form of a TNF inhibitor, or an IL-17 inhibitor if there is concurrent skin involvement. IL-17 inhibitors are more effective than TNF inhibitors for the treatment of patients with PsA and relevant skin involvement.41 However, IL-17 inhibitors are contraindicated for patients with PsA and inflammatory bowel disease, for which TNF, IL-12/23, IL-23 and JAK inhibitors are effective. Anti-TNF monoclonal antibody therapy is preferred for patients with uveitis. There are no clear guidelines on continuing csDMARD therapy in patients taking a bDMARD, and expert consensus suggests reducing the methotrexate dose in patients showing a good response to biologic therapy.40

JAK inhibitors are an emerging treatment option for PsA. Currently, the JAK inhibitors, tofacitinib and upadacitinib, are PBS listed for severe PsA, and are indicated for use in patients who have an inadequate response or intolerance to at least one bDMARD. The use of JAK inhibitors increases the risk of herpes zoster infection and, based on studies in other rheumatic populations, potentially carries an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular and thromboembolic events.42 Clinicians should therefore exercise caution if prescribing JAK inhibitors to older people (aged over 65 years), patients at high cardiovascular risk and those who are current smokers.

Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, may be considered for patients with mild disease who have shown an inadequate response to at least one csDMARD and for whom a treatment with bDMARD or JAK inhibitor is inappropriate.39 It is not currently PBS listed.

Immunisations and COVID-19

Immunocompromised individuals, including those with PsA, should routinely receive the following vaccinations: influenza, pneumococcal, meningococcal, human papilloma virus, hepatitis B, recombinant zoster and COVID-19. Moreover, the most updated Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation guidelines recommend that patients taking csDMARDs should receive the COVID-19 booster.43 Unless contraindicated, patients should receive all vaccines in accordance with the population immunisation schedule. Live vaccines are generally contraindicated for patients on immunosuppressive therapy and should be administered at least one month before starting treatment. Additionally, immunocompromised patients on bDMARD or tsDMARD therapy should not receive live vaccines until at least 12 months after therapy is ceased. Specialist advice is recommended for decisions on the use of live vaccines in immunocompromised patients, as individual risk may vary.44

People with an immune-mediated inflammatory disease and SARS-CoV-2 infection have risk factors for more severe COVID-19 outcomes, including higher disease activity and higher baseline glucocorticoid use, but not the DMARDs themselves.45 Therefore, patients who do not have active SARS-CoV-2 infection should continue taking DMARDs. Patients with PsA who contract SARS-CoV-2 should be prescribed antiviral medications according to guidelines, and the decision to withhold treatment should be determined on a case-by-case basis with specialist input.46 The current Australian Living Guideline for the Pharmacological Management of Inflammatory Arthritis suggests that PsA treatments do not need to be withheld around the time of COVID-19 vaccinations.47

Addressing comorbidities in people with psoriatic arthritis

Comorbidities, such as hypertension, metabolic syndrome, obesity, hyperlipidaemia, cardiovascular diseases and mood disorders, are common in people with PsA.48 Actively addressing comorbidities in the primary care setting optimises patient outcomes and aids in the selection of DMARDs.

Screening and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors, including hyperlipidaemia, hypertension and smoking, are essential for all patients with PsA. As previously discussed, use of certain therapies, such as JAK inhibitors, should be avoided in patients at high cardiovascular risk. Obesity is a significant comorbidity in PsA, and weight loss has shown to be beneficial in improving outcomes. Patients who are current smokers or have obesity should receive counselling for smoking cessation and weight loss, and be assessed for conditions such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes.

Anxiety and depression are also prevalent in patients with PsA and can lead to poor medication adherence and a reluctance to pursue systemic therapies. Effective management of mental health comorbidities can significantly enhance disease control and the quality of life in patients with PsA.49

Conclusion

PsA is a complex and varied disease that remains a major cause of disability and morbidity worldwide. The burden of disease on patients encompasses functional impairment in daily living caused by joint and skin symptoms, as well as the potential impact on overall quality of life, emotional wellbeing and the risk of long-term disability. Patients with PsA also experience an increased risk of comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease and depression.

A comprehensive approach to management is required because of the diversity of clinical manifestations in PsA. The treatment goals are to reduce inflammation, achieve remission and improve the patient’s overall quality of life. Early referral of the patient to a rheumatologist is important for escalation of therapies because only those with mild or limited disease are likely to respond to a trial of NSAIDs and local glucocorticoid injections. The treatment plan should consider the patient’s individual clinical presentation, comorbidities and preferences. As new targeted therapies emerge with varying efficacy for different features of PsA, clinicians should ensure patients undergo a regular review for ongoing monitoring and adjustment of therapies as needed. Shared decision-making between patients, GPs and specialists is therefore essential. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Karmacharya P, Chakradhar R, Ogdie A. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis: a literature review. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2021; 35: 101692.

2. Bavière W, Deprez X, Houvenagel E, et al. Association between comorbidities and quality of life in psoriatic arthritis: results from a multicentric cross-sectional study. J Rheumatol 2020; 47: 369-3676.

3. de Vlam, Kurt. Overview of psoriatic arthritis pathogenesis. In: FitzGerald O, Gladman D, eds. Oxford textbook of psoriatic arthritis. Oxford textbooks in rheumatology Online edition: Oxford Academic; 2018. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780198737582.003.0004 (accessed February 2024).

4. Kirkham B. Immunology and cytokine pathways. In: FitzGerald O, Gladman D, eds. Oxford textbook of psoriatic arthritis. Oxford textbooks in rheumatology Online edition: Oxford Academic; 2018. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780198737582.003.0007 (accessed February 2024).

5. Tiwari VB, Brent LH. Psoriatic arthritis Updated 7 January 2024. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547710/ (accessed February 2024).

6. Golder VS, Schachna L. Ankylosing spondylitis. Aust Fam Physician 2013; 42: 780-784.

7. Queiro R, Morante I, Cabezas I, Acasuso B. HLA-B27 and psoriatic disease: a modern view of an old relationship. Rheumatology 2015; 55: 221-229.

8. Chen L, Li J, Zhu W, et al. Skin and gut microbiome in psoriasis: gaining insight into the pathophysiology of it and finding novel therapeutic strategies. Front Microbiol 2020; 11: 589726.

9 Lubrano, E. Axial disease. In: FitzGerald O, Gladman D, eds. Oxford textbook of psoriatic arthritis. Oxford textbooks in rheumatology Online edition: Oxford Academic; 2018. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780198737582.003.0013 (accessed February 2024).

10. Gladman DD. Clinical features and diagnostic considerations in psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2015; 41: 569-579.

11. Kaeley GS, Eder L, Aydin SZ, Gutierrez M, Bakewell C. Enthesitis: a hallmark of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018; 48: 35-43.

12. Kaeley GS, Eder L, Aydin SZ, Gutierrez M, Bakewell C. Dactylitis: a hallmark of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018; 48: 263-273.

13. Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 251-265.e19.

14. Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA 2020; 323: 1945-1960.

15. Langley RG, Daudén E. Treatment and management of psoriasis with nail involvement: a focus on biologic therapy. Dermatology 2010; 221 Suppl 1: 29-42.

16. Olivieri I, Padula A, D’Angelo S, Cutro MS. Psoriatic arthritis sine psoriasis. J Rheumatol Suppl 2009; 83: 28-29.

17. Lambert JR, Wright V. Eye inflammation in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1976; 35: 354-356.

18. Freuer D, Linseisen J, Meisinger C. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a bidirectional 2-sample mendelian randomization study. JAMA Dermatol 2022; 158: 1262-1268.

19. Siba PR. Comorbidities of psoriatic arthritis — metabolic syndrome and prevention: a report from the GRAPPA 2010 Annual Meeting. J Rheumatol 2012; 39: 437-440.

20. Zhu TY, Li EK, Tam LS. Cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Int J Rheumatol 2012; 2012: 714321.

21. Ernste FC, Sánchez-Menéndez M, Wilton KM, Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Maradit Kremers H. Cardiovascular risk profile at the onset of psoriatic arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Care Res 2015; 67: 1015-1021.

22. Sumpton D, Kelly A, Tunnicliffe DJ, et al. Patients’ perspectives and experience of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arthritis Care Res 2020; 72: 711-722.

23. Woo YR, Park CJ, Kang H, Kim JE. The risk of systemic diseases in those with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: from mechanisms to clinic. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21: 7041.

24. Feld J, Chandran V, Haroon N, Inman R, Gladman D. Axial disease in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a critical comparison. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018; 14: 363-371.

25. Punzi L, Podswiadek M, Oliviero F, et al. Laboratory findings in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatismo 2007; 59 Suppl 1: 52-55.

26. Liu JT, Yeh HM, Liu SY, Chen KT. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Orthop 2014; 5: 537-543.

27. Crespo-Rodríguez AM, Sanz Sanz J, Freites D, et al. Role of diagnostic imaging in psoriatic arthritis: how, when, and why. Insights Imaging 2021; 12: 121.

28. Dominguez P, Husni ME, Garg A, Qureshi AA. Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire and the role of dermatologists: a report from the GRAPPA 2009 Annual Meeting. J Rheumatol 2011; 38: 548-550.

29. Tinazzi I, Adami S, Zanolin EM, et al. The early psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaire: a simple and fast method for the identification of arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Rheumatology 2012; 51: 2058-2063.

30. Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, Waxman R, Helliwell PS. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009; 27: 469-474.

31. Helliwell PS, Coates LC, Ransom M, et al; PROMPT Study Group. The comparative performance of three screening questionnaires for psoriatic arthritis in a primary care surveillance study. Rheumatology 2023; kead310.

32. Ogdie A, Coates LC, Gladman DD. Treatment guidelines in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology 2020; 59(Suppl 1): i37-i46.

33. Sumpton D, Oliffe M, Kane B, et al. Patients’ perspectives on shared decision-making about medications in psoriatic arthritis: an interview study. Arthritis Care Res 2022; 74: 2066-2075.

34. Sumpton D, Hannan E, Kelly A, et al. Clinicians’ perspectives of shared care of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis between rheumatology and dermatology: an interview study. Clin Rheumatol 2021; 40: 1369-1380.

35. Poddubnyy D. Managing psoriatic arthritis patients presenting with axial symptoms. Drugs 2023; 83: 497-505.

36. Laure G, Xenofon B, Andreas K, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020; 79: 700-712.

37. Merola JF, Ogdie A. SEAM-PsA: seems like methotrexate works in psoriatic arthritis? Arthritis Rheumatol 2019; 71: 1027-1029.

38. Lubrano E, Chan J, Queiro-Silva R, et al. Management of axial disease in patients with psoriatic arthritis: an updated literature review informing the 2021 GRAPPA Treatment Recommendations. J Rheumatol 2023; 50: 279-284.

39. Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020; 79: 700-712.

40. Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2022; 18: 465-479.

41. Philip JM, Josef SS, Frank B, et al; SPIRIT H2H study group. A head-to-head comparison of the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab and adalimumab in biological-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a randomised, open-label, blinded-assessor trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2020; 79: 123-131.

42. Ly K, Beck KM, Smith MP, Orbai AM, Liao W. Tofacitinib in the management of active psoriatic arthritis: patient selection and perspectives. Psoriasis 2019; 9: 97-107.

43. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation ATAGI. Recommendations on the use of a 3rd primary dose of COVID-19 vaccine in individuals who are severely immunocompromised. Version 4.3 Department of Health; Canberra, January 2024. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-01/atagi-recommendations-on-the-use-of-a-third-primary-dose-of-covid-19-vaccine-in-individuals-who-are-severely-immunocompromised.pdf (accessed February 2024).

44. Australian Immunisation Handbook. Vaccination for people who are immunocompromised. Department of Health and Aged Care: Canberra; 2023. Available online at: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/contents/vaccination-for-special-risk groups/vaccination-for-people-who-are-immunocompromised (accessed February 2024).

45. Pedro MM, Martin S, Satveer KM, et al. Characteristics associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes in people with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: data from the COVID-19 PsoProtect and Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registries. Ann Rheum Dis 2023; 82: 698-709.

46. Landewé RBM, Kroon FPB, Alunno A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management and vaccination of people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2: the November 2021 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2022; 81: 1628-1639.

47. Australian clinician guide for the use of immunomodulatory drugs in autoimmune rheumatic diseases at the time of COVID-19 vaccination. Version 1.1 8 November 2021. Available online at: https://anzmusc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Clinician-guide-for-the-use-of-immunomodulatory-drugs-in-autoimmune-rheumatic-diseases-at-the-time-of-COVID-19-vaccination-v1.1-20211108.pdf (accessed February 2024).

48. Gupta S, Syrimi Z, Hughes DM, Zhao SS. Comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 2021; 41: 275-784.

49. Zhao SS, Miller N, Harrison N, Duffield SJ, Dey M, Goodson NJ. Systematic review of mental health comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2020; 39: 217-225.

SERIES EDITOR: Associate Professor Arvin Damodaran BSc, MB BS(Hons), MMedEd, FRACP, representing the Education Training and Workforce Committee of the Australian Rheumatology Association.

SERIES EDITOR: Associate Professor Arvin Damodaran BSc, MB BS(Hons), MMedEd, FRACP, representing the Education Training and Workforce Committee of the Australian Rheumatology Association.